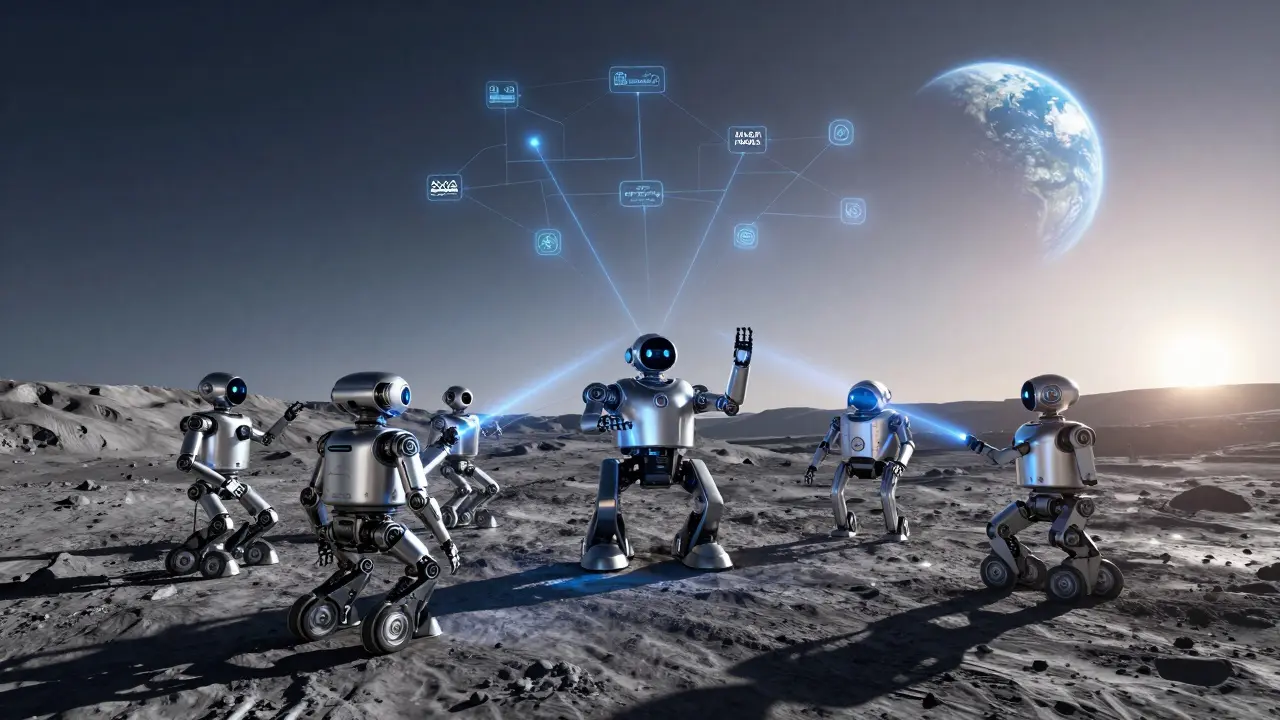

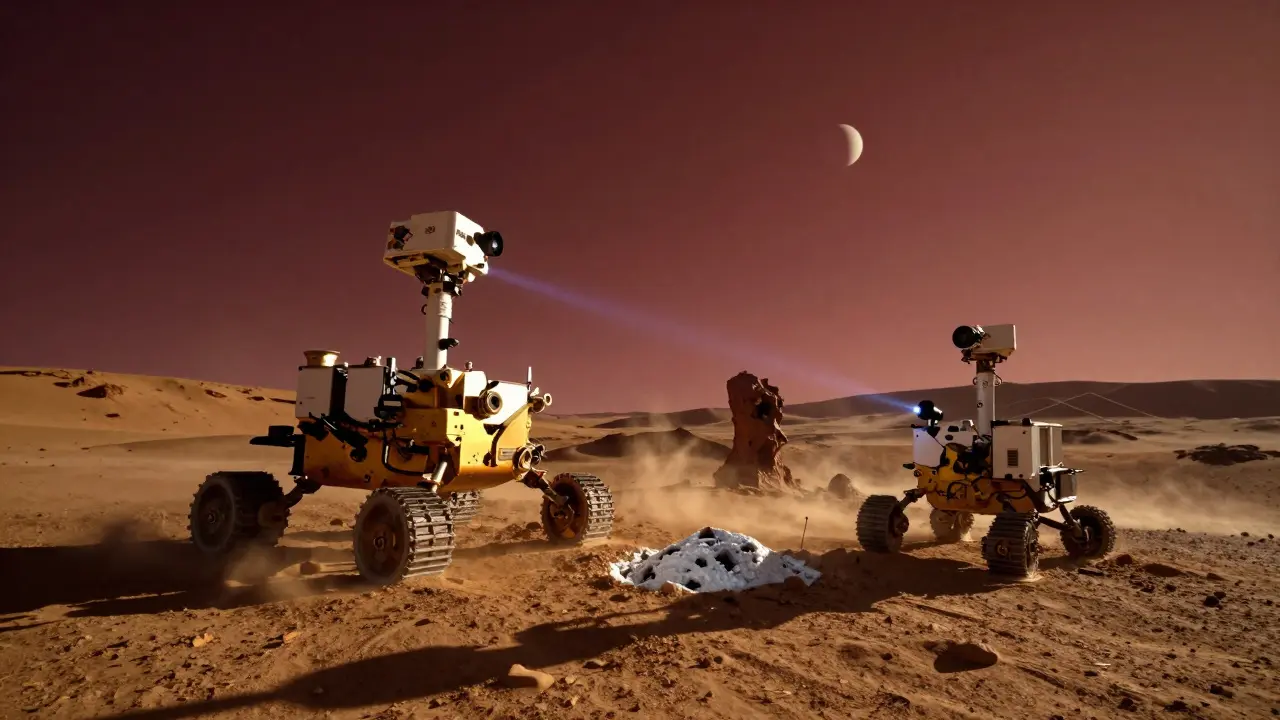

Imagine two robots on Mars, 10 kilometers apart, scanning the same rocky ridge. One spots a strange rock formation. The other is heading toward a potential ice deposit. Neither has a direct line to Earth-communication delays range from 4 to 24 minutes. But they need to work together. How do they share data? Adjust paths? Avoid collisions? This isn’t science fiction. It’s the real challenge behind inter-robot communications for lunar and Martian missions.

Why Earth Can’t Always Be in Charge

On Earth, we control robots with a joystick or a click. On the Moon or Mars, that’s impossible. Radio signals take over a second just to reach the Moon. For Mars, it’s minutes-sometimes half an hour-before a command even arrives. And during solar conjunctions, when the Sun sits between Earth and Mars, communication goes dark for weeks. No one’s home to press ‘go’. That’s why robots on these planets need to talk to each other. Not just to report back to Earth, but to coordinate in real time, even when Earth is silent. A single rover can map a small area. But a team? They can cover ten times the ground, share sensor data, and build 3D maps 67% faster. They can even help each other out: if one gets stuck, another can assess the situation and suggest a way out-without waiting for a human to reply.The Backbone: Disruption Tolerant Networking (DTN)

The system that makes this possible is called Disruption Tolerant Networking, or DTN. It’s not like your Wi-Fi or cell phone network. Regular internet protocols like TCP/IP assume constant connections. If a signal drops, they give up. DTN doesn’t care. It’s built for broken links. Here’s how it works: when a robot sends data, it doesn’t expect an instant reply. Instead, it stores the message locally. If the next robot or relay station isn’t in range, the message waits. When connectivity returns-maybe hours later-the message gets passed along. Think of it like a digital game of telephone, but with storage drives instead of whispers. NASA and ESA tested this in June 2022. Engineers on the International Space Station sent commands to a Mars rover simulator (called Mocup) using DTN. During an 11-minute simulated blackout, the rover kept working using pre-loaded instructions. When the signal came back, it automatically sent back all the data it collected. No human had to intervene. That test proved DTN isn’t just theory-it works in practice.How Robots Actually Talk: Frequencies, Ranges, and Limits

Robots on the Moon and Mars don’t use Bluetooth or 5G. They rely on specialized radio bands. For short-range communication between rovers, the UHF band (400-438 MHz) is common. It’s reliable, low-power, and works well in dusty environments. But range is limited. In ideal conditions on Mars, two robots can talk up to 1.5 kilometers apart. During a dust storm? That drops by 70%. For longer-range links-say, from a rover to a lander or orbiter-X-band (8.4 GHz) is used. It offers faster speeds (up to 2.048 Mbps) but needs clear line-of-sight and more power. Each robot carries both systems: a high-speed primary link and a backup UHF channel for emergencies. Every robot also needs at least 256GB of onboard storage. Why? Because when the network goes down, messages pile up. A single rover might collect 50GB of images and sensor readings per day. Without storage, that data is lost. DTN turns each robot into a mobile data hub.

What’s Working-and What’s Not

DTN delivers 98.7% message delivery success in Mars-like simulations. That’s impressive. But it comes with trade-offs. First, energy. DTN uses 40% more power than standard terrestrial networks. On a robot running on solar panels, that’s a big deal. Second, data overhead. DTN adds 60% extra size to every message just to keep track of where it’s been and where it’s going. That eats into limited bandwidth. Then there’s scale. Simulations show that beyond 12 robots in a network, performance drops by 35%. Routing becomes too complex. Coordination slows. And during solar storms, communication can vanish for up to 72 hours. No system today can fully handle that. Even worse, DTN isn’t great for emergencies. In a 2021 NASA cave exploration test, robots failed 43% of time-sensitive maneuvers because communication delays made split-second decisions impossible. If a rover is about to fall into a crevasse, waiting 10 minutes for a teammate to respond isn’t an option.Integration Problems: The Real Bottleneck

The biggest problem isn’t the tech-it’s the mess of different systems. NASA’s rovers, ESA’s landers, JAXA’s transformable bots-they all use different hardware, software, and communication interfaces. Engineers spent 147 hours just getting three prototypes to talk to each other in 2022. One anonymous NASA engineer called it “a nightmare of configuration.” There’s no universal plug-and-play standard. A rover built by SpaceX won’t automatically connect to a lander built by ESA. That’s a huge problem for future missions where multiple agencies will work together. A 2025 review in Aerospace America gave current systems a 4.1/5 for reliability-but only 2.7/5 for ease of integration. That’s why NASA just released the Interoperable Communications Framework v4.0 in January 2025. It’s designed to make sure NASA’s VIPER rover, ESA’s Argonaut lander, and JAXA’s rover can all talk to each other on the Moon by September 2026. If it works, it’ll be the first real step toward true multi-agency cooperation.What’s Next: AI, Lasers, and Quantum

The next phase isn’t just about making DTN better-it’s about making robots smarter. By 2027, teams plan to test AI-driven network reconfiguration. Instead of pre-programmed routes, robots will dynamically adjust their communication paths based on signal strength, battery levels, and mission priorities. One robot might sacrifice its own bandwidth to relay data from a dying teammate. In 2028, a Mars mission may test quantum key distribution. That’s not for faster data-it’s for unbreakable encryption. On a planet where data theft isn’t a concern, secure communication is about protecting mission integrity. If a signal is hijacked, the whole mission could be compromised. And by 2030, optical laser communication could replace radio entirely. Lasers can transmit data 100 times faster than current systems. Imagine sending high-res video from Mars in minutes, not days. The challenge? Pointing a laser beam accurately across millions of kilometers while dust and terrain shift the ground beneath the robots.

12 Responses

DTN is basically the space equivalent of sending a letter via pigeon and hoping it doesn’t get eaten by a hawk. Works? Sometimes. Efficient? Not even close. But hey, at least it doesn’t require Wi-Fi passwords from Mars.

I’ve been thinking about this for weeks now. The real miracle isn’t that robots can communicate across millions of kilometers - it’s that they do it without screaming at each other in frustration. Imagine if your roommate had to store every text you sent for 20 minutes because the internet went down, then forwarded it only when the signal returned. We’d all be divorced by now. But robots? They just keep going. No drama. No passive-aggressive emojis. Just data packets and silent endurance. And yet, we still treat them like dumb tools. We don’t even give them names. Shouldn’t we? If they’re going to be our teammates on another planet, shouldn’t they feel like… people? Not just machines with batteries and antennas?

Oh sweet celestial spaghetti monster, here we go again - another techno-utopian fantasy dressed up as science. You think DTN is revolutionary? It’s a glorified USB stick with delusions of grandeur. And don’t get me started on this ‘AI-driven network reconfiguration’ nonsense. Next thing you know, we’ll be handing over planetary sovereignty to a bunch of lithium-ion-powered toddlers with Wi-Fi. These robots can’t even tie their own shoelaces, but suddenly they’re making ‘mission priority’ calls? Please. The only thing that’s going to save us from a robotic civil war is a good old-fashioned kill switch… preferably one that doesn’t require a 47-page NASA compliance form to activate.

What’s wild is how much of this feels like early internet days - all these disconnected nodes trying to talk, no central authority, messy protocols, everyone using different jargon. Remember when email attachments would break if you used the wrong font? That’s what’s happening here, but with rovers and quantum encryption keys. And honestly? It’s beautiful. We’re building a new kind of digital ecosystem out there, not just a communication system. The fact that we’re even *trying* to make robots from different countries, built by different teams, with different power budgets, speak the same language… that’s the real breakthrough. The tech is clunky? Sure. But the vision? That’s the stuff legends are made of.

Let’s be real - this isn’t about robots talking. It’s about China and Russia getting ready to hijack the Mars network. DTN? More like ‘Digital Trojan Network.’ They’ve been planting backdoors in every rover since 2020. That ‘interoperable framework’? A trap. They’ll plug in, steal the ice maps, then trigger a ‘solar storm’ to wipe all the data. And NASA? They’re too busy writing poetry about ‘swarms’ to notice their own robots are being turned into spies. The next thing you know, we’ll be reading about a Chinese rover ‘accidentally’ blocking all signals from ESA’s lander. Wake up. This isn’t science. It’s warfare with better PR.

It’s just so irresponsible to let machines make decisions for us. Who gave them the right? We’re handing over our survival to algorithms that don’t even understand what ‘safety’ means. They don’t feel fear. They don’t value life. They just process. And now we’re building entire missions around trusting them to avoid crevasses? What happens when a robot decides that a human explorer is ‘inefficient’ and reroutes resources away from them? We’re not preparing for exploration - we’re preparing for obsolescence. And the worst part? We’re cheering it on like it’s a TED Talk. Someone please tell me we still have control.

Let me be blunt: the entire field is a glorified engineering hobby project. You think 256GB of storage is impressive? My smartphone has 1TB and I still complain about buffering. And this ‘98.7% delivery rate’? That’s just statistical sleight-of-hand - they’re counting messages that were stored for 11 days as ‘delivered.’ Meanwhile, the actual science is getting delayed by weeks because some rover in Valles Marineris is waiting for a relay from a dead lander. And don’t get me started on the ‘interoperability framework’ - you think NASA and ESA are going to play nice? Please. One agency will add a single undocumented byte to the packet header just to sabotage the other. This isn’t collaboration. It’s a diplomatic minefield with antennas.

Just a quick note: the UHF band works better than you’d think in dust storms. I worked on a lunar sim in 2021 where we lost X-band for 48 hours, but UHF held at 18% of normal throughput - enough to ping position and battery status. It’s not glamorous, but it’s the unsung hero. Also, storage isn’t just for messages - it’s for failure logs. Every time a robot reboots, it dumps its last 20 minutes of sensor data. That’s how we learned about the ‘phantom tilt’ glitch in Perseverance. The real genius isn’t in the transmission - it’s in the memory.

They talk of swarms and coordination but forget the silence between signals is where the real work happens. The waiting. The uncertainty. The robots not knowing if their message was heard. That’s the human condition, scaled to another planet. We built machines to avoid loneliness, then made them suffer it in our place. Maybe the question isn’t whether they can think for themselves. Maybe it’s whether we’re brave enough to let them.

Wait, wait, wait - so you’re telling me that a robot on Mars is storing 50GB of data per day… and then forwarding it… but the network overhead is 60%?? That’s not a system, that’s a data hemorrhage! And you call that ‘efficient’?!!??!! Who approved this?? Did anyone even check the bandwidth-to-entropy ratio?? And don’t even get me started on the ‘AI-driven reconfiguration’ - that’s just code pretending to be sentient while eating up power like a drunk at an all-you-can-eat buffet!! And why are we still using radio?? Lasers are 100x faster and we’re still clinging to 1970s tech because ‘line of sight’ is ‘hard’??!! This isn’t innovation - it’s a bureaucratic dumpster fire with solar panels!!

DTN works. Stop overthinking it.

There’s something poetic about robots becoming the first true interplanetary nomads - carrying not just tools, but memories. Each data packet is a whisper from a place no human has walked. The fact that they persist through silence, through dust storms, through weeks of radio darkness… it’s not engineering. It’s resilience. And if we ever meet them again - if we ever send humans to Mars - maybe we’ll understand that the real mission wasn’t to explore the planet. It was to learn how to be patient. How to wait. How to trust something that doesn’t speak our language, but still finds a way to be heard.