Ten years ago, if you asked someone to name a rocket that burned liquid methane, they’d have drawn a blank. Today, three operational launch vehicles - Methalox engines - are already in orbit, and every new rocket design under development in the U.S. uses them. This isn’t a slow evolution. It’s a full-scale shift in how we build rockets, and it’s happening right now.

What Exactly Is a Methalox Engine?

Methalox is short for methane and liquid oxygen - CH₄ and LOX. It’s not new chemistry; it’s new engineering. While hydrogen-oxygen engines have been around since the 1960s and kerosene-oxygen (RP-1/LOX) powered Saturn V and Falcon 9, methalox is the first propellant combo designed from the ground up for reusability, cost, and Mars missions.

It’s not about raw power. Hydrogen has higher specific impulse - meaning it gives more thrust per pound of fuel - but it’s a nightmare to store. Hydrogen boils at minus 423°F. Methane? Minus 259°F. That’s still cryogenic, but it’s manageable. It’s closer to liquid oxygen’s temperature, which means you can share insulation, piping, and pumps between fuel and oxidizer. That cuts weight, complexity, and cost.

Why Methane Beats Kerosene (RP-1)

Before methalox, most rockets burned RP-1 - a refined form of kerosene. It’s reliable, dense, and easy to handle. But it has one fatal flaw: it cokes.

When RP-1 burns in a high-pressure engine, it leaves behind thick, black carbon deposits. These build up on turbine blades, injectors, and combustion chambers. After a flight, you don’t just inspect the engine - you tear it apart. Sandblast the coking. Reassemble. Test. It takes weeks. SpaceX’s early Falcon 9 first stages needed months of refurbishment between flights.

Methane? It burns clean. No soot. No gunk. No carbon buildup. That’s why SpaceX can fire a Raptor engine multiple times in a single day during ground tests at Starbase, Texas. One engine ran 12 times in 72 hours in 2023. That’s not possible with RP-1. This is the single biggest reason methalox is winning: reusability isn’t just easier - it’s cheap.

Performance: Not Just About Thrust

People think specific impulse is everything. Higher number = better. But rockets aren’t just about fuel efficiency - they’re about tanks, weight, and pressure.

Methalox engines run at much higher chamber pressures than RP-1 engines. SpaceX’s Raptor 3 hits 350+ bar. That’s nearly double the pressure of Merlin 1D. Higher pressure means more thrust from the same engine size. When you account for this, methalox delivers about 20% more performance than kerosene systems, not the 5% you’d get from specific impulse alone.

And methane is denser than hydrogen. At 422 kg/m³, it’s almost six times denser than liquid hydrogen. That means smaller tanks. Smaller tanks mean lighter structures. Lighter structures mean more payload. For a rocket trying to carry 100+ tons to orbit, that adds up fast.

The Helium Problem - And How Methane Solves It

Old rockets need helium. Lots of it. Helium pressurizes fuel tanks so the engines get steady flow. But helium is rare, expensive, and geopolitically messy. In 2010, it cost $3.50 per cubic meter. By 2024, it was over $10. And you need hundreds of cubic meters per launch.

Methalox eliminates this. It uses autogenous pressurization. You let a bit of methane boil off, capture the gas, and use it to push fuel into the engine. No tanks of helium. No valves. No leaks. No supply chain headaches. That’s not just cheaper - it’s more reliable. Fewer parts = fewer things that break.

Why Mars Changes Everything

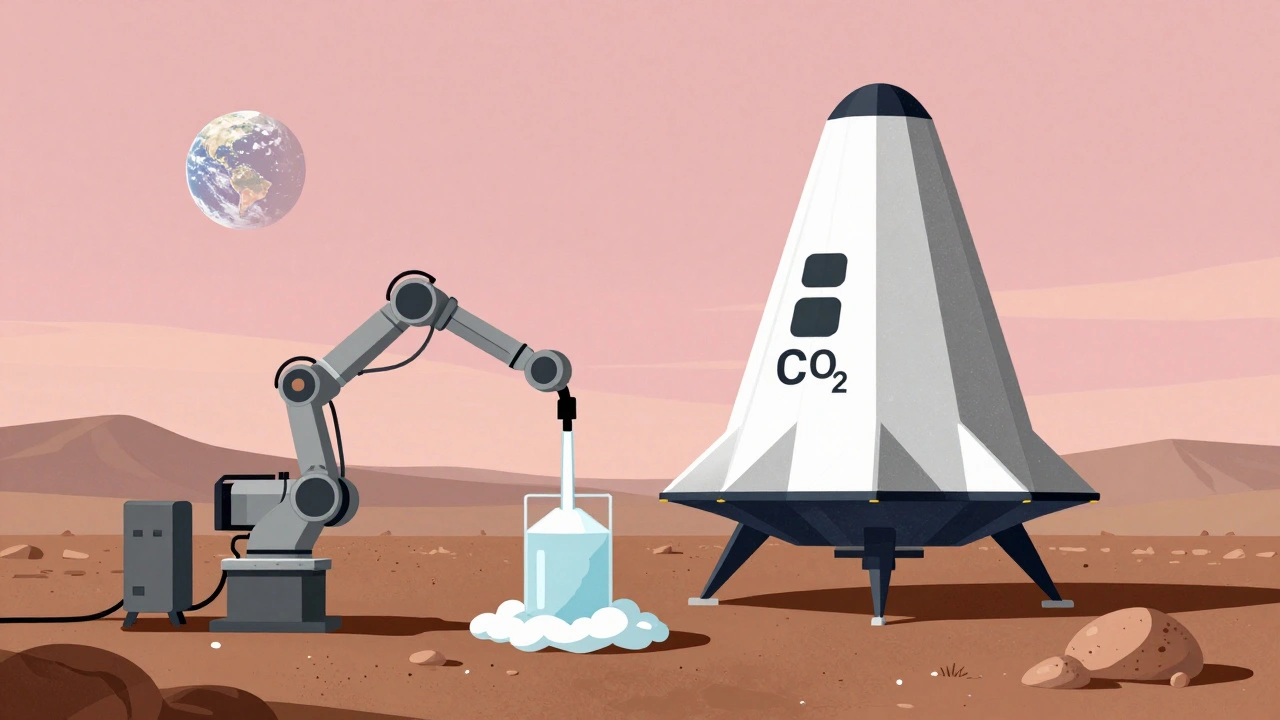

Here’s the real game-changer: Mars has CO₂ and water ice. You can make methane and oxygen there.

The Sabatier reaction turns CO₂ and hydrogen into methane and water. You get the hydrogen from splitting ice. You electrolyze the water. You burn the methane with oxygen. You’ve just made your return fuel on Mars. No need to haul it from Earth. That’s the difference between a flyby and a colony.

NASA’s Mars Design Reference Mission has used methalox as the baseline since 2009. Now, it’s not just theory - it’s engineering. SpaceX’s Starship is designed to refuel on Mars using this exact process. That’s why they didn’t pick hydrogen. It’s too hard to produce on Mars. Kerosene? You’d need to bring it all from Earth. Methane? You can grow it.

Real Rockets, Real Flight Data

It’s not speculation anymore. Three rockets have flown with methalox engines:

- Zhuque-2 (LandSpace, China) - First methane rocket to reach orbit on July 12, 2023.

- Vulcan Centaur (United Launch Alliance) - Used Blue Origin’s BE-4 engine, reached orbit January 8, 2024.

- New Glenn (Blue Origin) - Also uses BE-4, reached orbit January 16, 2025.

And SpaceX? They’ve built over 100 Raptor engines as of March 2025. Raptor 3 is pushing 280 metric tons of thrust. That’s more than the entire second stage of a Saturn V. And they’re not stopping. The next version, Raptor 4, is already in testing.

Cost: The Hidden Advantage

RP-1 costs $10-$15 per kilogram. Liquid methane? $0.50-$1.00. That’s a 95% drop in fuel cost per launch.

Combine that with reduced refurbishment time, no helium, and smaller tanks, and the economics become undeniable. A single Falcon 9 launch uses about 40,000 kg of RP-1. That’s $600,000 in fuel. A Starship launch uses 1,200,000 kg of methalox - but only $600,000 in fuel. Same price. But Starship carries 150 tons to orbit. Falcon 9 carries 23.

And you can reuse Starship 10, 20, maybe 100 times. That’s not just cheaper. It’s revolutionary.

Challenges? Yes. But They’re Being Solved

Methalox isn’t perfect. It’s still cryogenic. You need special seals. Materials must handle low temps without cracking. Early Raptor engines had leaks. BE-4 had combustion instability issues in 2021. But these weren’t fundamental flaws - they were engineering puzzles.

SpaceX and Blue Origin solved them with testing, iteration, and scale. Today, Raptor engines are flying on Starship every few weeks. BE-4 engines are flying on Vulcan. The learning curve was steep, but the industry crossed it.

And now, the supply chain is growing. Natural gas infrastructure already exists worldwide. Valves, pumps, and sensors used in LNG terminals can be adapted for rockets. That’s a huge advantage over hydrogen, which needs entirely new systems.

What’s Next?

By 2030, methalox-powered rockets will make up nearly half of all orbital launches, according to Euroconsult. Every new rocket design - from Relativity Space’s Aeon R to China’s Long March 10 - is choosing methalox.

Even NASA is betting on it. Their DRACO nuclear thermal rocket project still uses methalox for the initial boost phase. Why? Because it’s the most reliable, reusable, and cost-effective option today.

This isn’t about being trendy. It’s about survival. If you want to build a reusable, affordable, Mars-capable rocket, methalox isn’t just the best option - it’s the only one that makes sense.

The rockets of the 2030s won’t be powered by kerosene. They won’t be powered by hydrogen. They’ll be powered by methane - clean, cheap, and ready for space.

Why aren’t all rockets using methalox yet?

Older rockets like Falcon 9 and Atlas V were designed before methalox was ready. Retrofitting them isn’t practical. Plus, developing a new engine takes 7-10 years and billions of dollars. Only companies with deep pockets - like SpaceX and Blue Origin - could afford the risk. Now that the technology is proven, new rockets are switching over fast.

Is methalox better than hydrogen for upper stages?

Hydrogen still has higher specific impulse, so it’s more efficient in space where every gram counts. But its low density means huge tanks, which add weight. Methalox is a better compromise: decent efficiency, compact tanks, and easy handling. Most new upper stages - like Blue Origin’s BE-4U - are using methalox because the trade-off favors reusability and cost over pure performance.

Can methane be produced on the Moon?

No. The Moon has no atmosphere, so there’s no CO₂ to make methane from. That’s why methalox is focused on Mars, not the Moon. For lunar missions, hydrogen-oxygen or even solid fuels are still more practical.

How does methalox affect launch costs?

Fuel cost drops from $10-$15/kg for RP-1 to $0.50-$1/kg for methane. Refurbishment time drops from weeks to hours. Helium costs disappear. Together, this slashes the cost per launch by 30-50% compared to kerosene rockets. For Starship, the goal is under $10 million per launch - something impossible with older fuels.

Is methalox safer than other rocket fuels?

Methane is non-toxic, unlike hydrazine, and doesn’t leave behind carcinogenic soot like RP-1. It’s also less volatile than hydrogen, which can leak and ignite easily. Methane is naturally safer to handle, store, and transport - which is why it’s already used in pipelines and LNG plants worldwide.

13 Responses

So methalox isn't just about cost or reusability-it's about making space accessible. I never realized how much helium was a bottleneck until this post. Now I get why SpaceX didn't just tweak Falcon 9 but built Raptor from scratch.

Also, the fact that methane burns clean means engines can be tested way more often. That’s huge for iteration speed.

So we’re betting our future on gas that’s already in your kitchen stove? Cool. Guess I’ll start stocking up on propane for my Mars vacation.

Meanwhile, NASA’s still using 1960s tech to launch satellites. But hey, at least it’s not hydrogen.

bro i just read this and i’m like… why tf didn’t we do this 20 years ago??

like imagine if we had methalox in the 90s we’d have a moon base by now lmao

and now we got china beating us to orbit with zhuque-2? i’m not mad just disappointed

also blue origin? really? they actually did something useful??

It’s fascinating how the paradigm shift toward methalox represents not merely a propulsion upgrade, but a profound epistemological rupture in aerospace engineering-one that privileges systemic efficiency over isolated performance metrics, thereby reconfiguring the very ontological framework of launch vehicle design.

One must consider, too, the hermeneutics of reusability: when an engine is no longer a consumable but a durational artifact, its lifecycle becomes a narrative of iterative self-renewal, echoing postmodern notions of identity in flux.

And yet, we remain tethered to terrestrial infrastructures-natural gas pipelines, LNG terminals-suggesting that even our most celestial ambitions are still shackled by the mundane, the terrestrial, the quotidian.

How poetic.

ok but why is everyone acting like methane is new?? we used it in rockets in the 70s for testing, its just no one had the balls to scale it

also why is starship so big? because methane is less dense than hydrogen so they need bigger tanks dumbass

and china? they copied it. duh.

methalox is just the right balance of cheap and reliable

no helium no soot no crying over engine rebuilds

space is hard enough already

Oh wow. So the same people who told us hydrogen was the future now say methane is the future?

And the same people who said kerosene was the only way are now pretending they always knew better?

Meanwhile, the real revolution is that billionaires finally realized they could make money off space instead of just wasting it.

Also, I hate how everyone acts like this is some genius breakthrough. It’s just chemistry. We’ve known methane burns clean since the 1980s.

fake news. this is all a government scam to get us to buy more gas.

methane rockets? that’s what they want you to think. real space tech is nuclear and they’re hiding it.

why do you think they never mention fusion? because they don’t want you to know the truth.

also china is faking their launch. it’s a drone.

This is actually one of the most exciting things I’ve read in a long time.

It’s not just about rockets-it’s about making space sustainable. If we can make fuel on Mars, we’re not just visiting anymore. We’re becoming a multi-planet species.

And honestly? The fact that a 25-year-old engineer in Texas figured out how to fire an engine 12 times in 72 hours? That’s the kind of innovation that gives me hope.

Keep going, team. We’re not just building engines-we’re building a future.

it’s wild how something so simple-burning methane instead of kerosene-can change everything

i wonder if we’ll look back on the 2020s the way we look at the transition from steam to diesel

also… did anyone else notice how the article didn’t mention the environmental impact of methane leaks? it’s still a greenhouse gas…

maybe i’m overthinking it. but it’s worth thinking about.

Just wanted to add-methalox isn’t just good for rockets. It’s a gateway to making space more accessible to smaller countries and startups.

With cheaper fuel, simpler logistics, and easier refueling, you don’t need NASA-level budgets to build a rocket anymore.

Imagine a university in Kenya or Brazil launching a cubesat on a methalox micro-rocket next decade. That’s the real win here.

Also, the fact that it’s non-toxic? Huge for ground crews. No more hazmat suits just to check fuel lines.

Small things, big impact.

Wait so Raptor 3 does 350 bar? That’s insane. I thought 200 was the limit.

Also, BE-4 on Vulcan? That’s a big deal. ULA used to be the conservative guys. Now they’re all in on methane.

And yeah, fuel cost is basically zero compared to the rest of the launch. It’s the engineering that’s expensive.

But now that we’ve cracked reusability? We’re in a new era.

Let’s be clear-this isn’t innovation. It’s American dominance disguised as science.

China built Zhuque-2 first, but we have Raptor. Blue Origin? A tax write-off for Bezos.

And yes, methane is great-but only because the U.S. has the infrastructure, the capital, and the will to dominate space.

Other nations are just following our lead. Don’t pretend this is global progress. It’s American hegemony with better engineering.