Every satellite you see in the sky - whether it’s streaming your favorite show, tracking weather patterns, or connecting remote villages - depends on a hidden global system to stay on the air. That system is run by the International Telecommunication Union (a United Nations agency responsible for managing global radio frequencies and satellite orbits, ITU). Without its filing rules, satellites from different countries would crash into each other’s signals, leaving millions without GPS, internet, or emergency communications. This isn’t science fiction. It’s the real, complex, and often frustrating process that keeps space functional.

Why the ITU Matters More Than You Think

The ITU isn’t a space agency. It doesn’t launch rockets. But without it, space would be chaos. Think of it like air traffic control - but for radio waves and orbital slots. Every time a company or country wants to put up a satellite, they must file with the ITU to claim a specific frequency band and orbital position. These aren’t just technical details. They’re legal rights. Once registered in the Master International Frequency Register (the official global database of all registered satellite networks, MIFR), those rights are protected under international law.

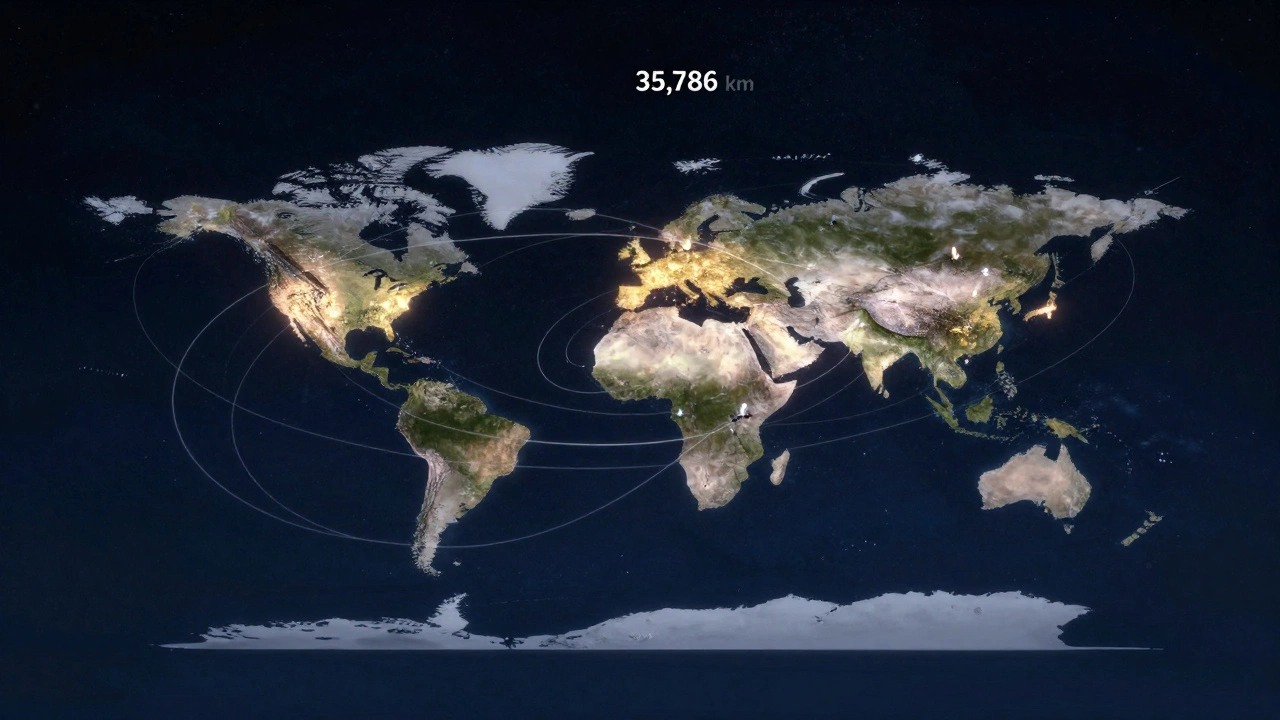

There are over 6,000 satellite networks listed in the MIFR as of 2025. That number is growing fast - up 14.7% every year since 2018. And it’s not just big players. Small nations, startups, and research groups are filing too. But here’s the catch: space isn’t infinite. There are only so many usable orbital slots, especially in the crowded Geostationary Orbit (a fixed position 35,786 km above the equator where satellites match Earth’s rotation, GSO). And only certain radio frequencies can carry high-speed data without interference. That’s why the ITU’s filing system is the only thing standing between a functional global satellite network and total signal chaos.

The Two Paths to Claiming Space

There are two ways to file with the ITU, and they couldn’t be more different.

The first is the Coordination Approach (a first-come, first-served system where early filers get priority). This is how most big companies and established space nations play the game. If you file first, you get dibs. It’s simple, but it’s also unfair. The U.S., Russia, China, and the EU control over 63% of all active filings. Countries with fewer resources often get locked out before they even start.

The second is the Planning Approach (a system designed to reserve slots for future use by developing nations). This was meant to level the playing field. Nations can submit long-term plans for satellite networks they intend to launch in 10 or 15 years. But in practice, it rarely works. Most of these plans are never followed up. Meanwhile, the Coordination Approach keeps eating up the best spots.

The result? A two-tiered system. Wealthy nations and corporations race to grab the best frequencies and orbits. Others are left waiting - or worse, left out.

The Five Steps to Get Your Satellite on the Air

Getting approved isn’t just filling out a form. It’s a multi-year marathon with legal, technical, and diplomatic hurdles. Here’s what it actually takes:

- Gather your data - You need exact details: satellite weight, power output, frequency range, orbital height, antenna patterns. Missing one number? Your filing gets bounced.

- Check compliance - Your satellite can’t exceed power limits or interfere with existing systems. The ITU has strict formulas for this. Many filings fail here because operators underestimate how much their signal could bleed into others’ bands.

- Negotiate with other countries - You must contact every nation whose satellites might be affected. On average, you’ll need to coordinate with 12 other countries. Some negotiations take months. Others drag on for years.

- Submit to the MIFR - Once everyone agrees (or at least doesn’t object), you file the final package. This step alone can take 6-18 months.

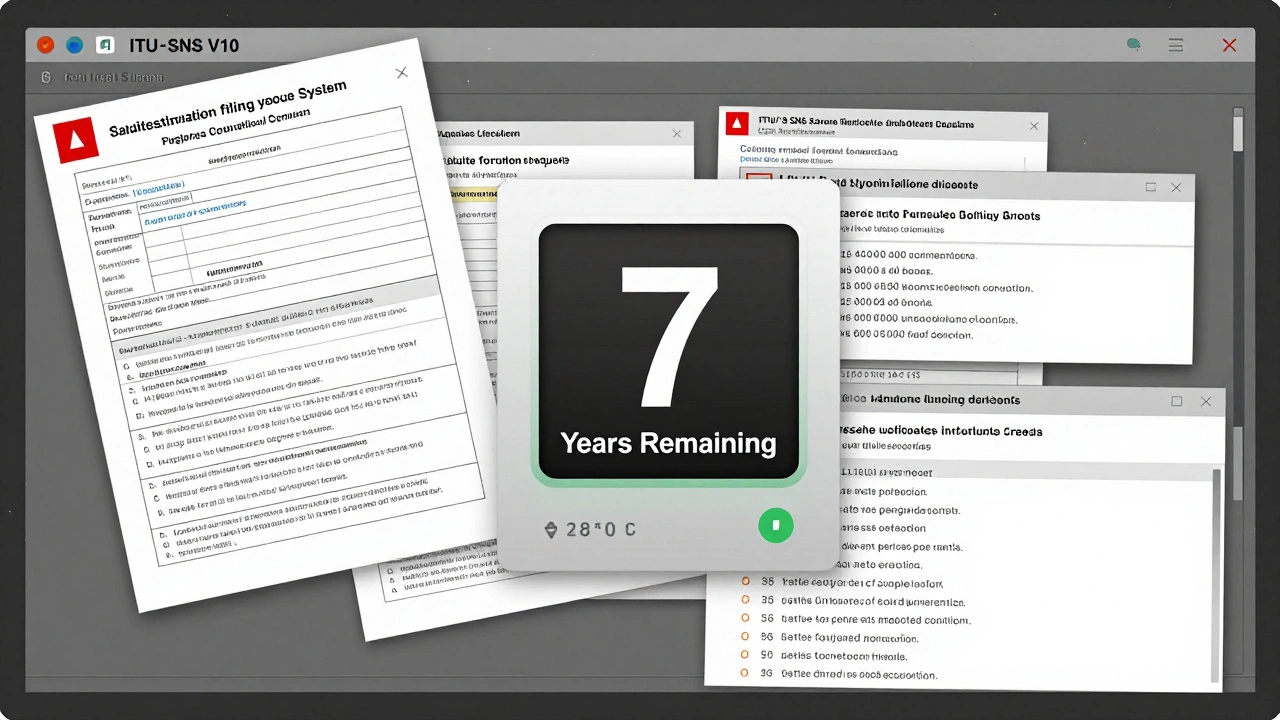

- Launch within seven years - This is the kicker. If you don’t launch your satellite within seven years of registration, the ITU cancels your rights. Forever. No extensions. No exceptions.

Most commercial operators report the entire process takes 3-5 years. For small operators or new nations, it can stretch to seven. And if you miss that seven-year deadline? You lose your spot. Someone else gets it.

The Paper Satellite Problem

Here’s the dirty secret: a lot of filings are fake.

Some countries and companies file for orbital slots they have no intention of using. They do it to block competitors. Or to sell the rights later. This is called the “paper satellite” problem.

One infamous case: Tonga filed for 48 orbital positions in the 1990s. Tonga has no satellite industry. No launch capability. No engineers. Yet, it held onto those slots for decades - leasing them to foreign companies for millions. The ITU didn’t stop it. Why? Because until 2025, they only took filings at face value.

That’s changing. Since January 1, 2025, the ITU requires proof of real progress: manufacturing contracts, launch agreements, in-orbit testing plans. No more “I’ll launch someday.” You need to show you’re building the satellite now. If you can’t prove it? Your filing gets rejected.

But the damage is done. Thousands of slots are still tied up by ghost filings. And until every country enforces these rules equally, the system remains vulnerable.

The New Rules: SNS V10 and Resolution 49

Big changes came in 2025. The ITU switched from its old filing system to the Space Notification System (the new mandatory digital platform for all satellite filings, SNS V10). All filings must now go through this online portal. No paper. No email. No exceptions.

It’s faster - if you know how to use it. But in the first quarter of 2025 alone, 187 filings were rejected because operators didn’t format their data correctly. The learning curve is steep. Many small operators got caught off guard.

At the same time, Resolution 49 (a 2019 rule now fully enforced as of 2025) cracked down on speculative filings. You can’t just claim a slot anymore. You must prove you’re building the satellite, have a launch contract, and have a timeline for testing. It’s a major step toward fairness.

But it’s not perfect. The ITU still doesn’t verify launch dates. A company can say they’re launching in 2027 - and the ITU accepts it. Until that satellite actually flies, the slot remains blocked.

Who’s Winning? Who’s Losing?

The numbers tell a clear story:

- United States: 38.2% of all active filings

- Russia: 9.7%

- China: 8.5%

- European Union: 7.3%

That’s 63.7% controlled by four blocs. Meanwhile, developing nations average just 0.3 filings per year. Some have never filed at all.

The World Bank (an international financial institution tracking global space access disparities) calls this the “regulatory divide.” It’s not just about money. It’s about access to knowledge, legal expertise, and technical support. The ITU offers training, but it’s not enough. Most countries need 18-24 months just to build the internal capacity to file correctly.

And then there’s the rise of mega-constellations. SpaceX’s Starlink alone has over 6,000 satellites in orbit. Amazon’s Project Kuiper is coming. These systems file hundreds of frequencies at once. They can afford to wait years. Smaller players can’t. The system was never designed for this scale.

What Happens Next?

By 2030, experts predict over 32,000 active satellites. That’s more than all satellites ever launched in the past 70 years combined. The ITU’s current system is already strained. Without major reform, coordination conflicts could jump 220% by 2030.

There are signs of progress. The ITU now requires spectrum sharing in certain bands. It’s speeding up small satellite filings. And the new enforcement rules are starting to clear out dead filings.

But the big questions remain: How do you make space fair? Can a first-come-first-served system work in a world where only a few can afford to play? And what happens when the last usable orbital slot is taken?

Right now, the ITU is the only game in town. It’s messy, slow, and imperfect. But without it, the sky would be silent - not because satellites failed, but because no one could agree on who gets to use the airwaves above us.

What You Need to Know If You’re Planning to Launch a Satellite

- Start early - the process takes years. Don’t wait until you have your satellite built.

- Use the SNS V10 system. Everything else is obsolete.

- Document everything. Missing a single technical spec can delay you by months.

- Don’t file for more than you need. You’ll get flagged as a paper satellite.

- Know your seven-year deadline. Miss it, and you lose everything.

- Work with your national regulator. They’re your best resource for navigating the process.

What happens if two countries file for the same satellite slot?

If two filings conflict, the ITU triggers a coordination process. Both parties must negotiate technical changes - like adjusting frequencies or power levels - to avoid interference. If they can’t agree, the ITU steps in to mediate. The first filer usually gets priority, but the second party can argue for equitable access if they can prove their use is more efficient or serves a public need. This process can take years.

Can a private company file with the ITU directly?

No. Only national telecommunications regulators can file on behalf of companies. SpaceX, for example, doesn’t file itself. The U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) does it for them. This means private operators must work through their country’s authority, which can add delays or political hurdles.

Why can’t we just auction off orbital slots like radio frequencies on Earth?

Because space law forbids it. The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 says no country can claim sovereignty over space or its resources. Auctions would imply ownership - which is illegal. The ITU’s system is the only legal alternative: it assigns temporary usage rights, not ownership. Any market-based system would violate international law.

How do I check if a satellite frequency is already taken?

Use the ITU’s BR IFICs database, which contains over 15,000 past coordination cases. It’s free to access and shows all registered satellite networks, their frequencies, and their status. Most national regulators also provide tools to help you search before filing. Never skip this step - overlapping frequencies cause real-world interference.

What’s the difference between GSO and non-GSO satellites in ITU filings?

GSO satellites sit in one fixed spot above the equator. Their slots are extremely limited and heavily contested. Non-GSO satellites (like Starlink) move in lower orbits and can share space more easily. But they require many more filings because they’re in constellations. Since WRC-19, non-GSO filings have mandatory deployment milestones - 10% of the constellation must be launched within 2 years, 50% within 5 - to prevent hoarding.

Final Thoughts: A System on the Edge

The ITU’s satellite filing system isn’t broken. It’s stretched thin. It was built for a world with dozens of satellites. Now we’re heading toward tens of thousands. The rules are getting tougher, the tech is getting better, and the pressure is rising.

For now, it still works. Interference between satellites is rare - 85% of operators say the system prevents collisions effectively. But that’s only because the system is being held together by patches and last-minute fixes.

The real test is coming. As more nations join the space race, and as private companies launch more satellites than governments ever did, the ITU will need to evolve. Fairness, speed, and transparency aren’t optional anymore. They’re the only way space stays open to everyone - not just the ones who got there first.

13 Responses

The ITU system is a mess, but it’s the only thing keeping satellites from blasting each other into space debris. I’ve worked with small NGOs trying to launch weather sensors, and the paperwork alone could fill a library. No one talks about how long it takes just to get a technical spec approved.

Oh, so now we’re pretending this isn’t just colonialism with satellites? The U.S. and EU hoard slots like they’re buying concert tickets while countries with actual needs get locked out. And don’t get me started on Tonga’s 48 ghost satellites. If this were a stock market, it’d be shut down for insider trading.

China and Russia are gaming the system too. Don’t act like the U.S. is the villain. We’re just better at playing the game. If you can’t file right, don’t blame the rules.

As someone from Canada who’s watched this unfold, I’ve seen our own regulator struggle to keep up. We’re not rich, but we’re not poor either. The real tragedy? The ITU’s training workshops are held in Geneva and D.C. No one in rural Nepal or Bolivia can afford to send their engineer there. It’s not just about money - it’s about access.

So the new SNS V10 system is supposed to fix everything? Bro. I tried uploading a file last month. The portal rejected it because my antenna gain was listed as 24.5 dBi instead of 24.50. That’s not progress. That’s a glitchy spreadsheet with a fancy UI.

My cousin works at a startup trying to launch a CubeSat for wildfire monitoring. They spent 18 months just getting their frequency coordination draft approved. Meanwhile, a hedge fund in Singapore filed for 12 orbital slots last year - and they don’t even have a lab. The system’s rigged, but nobody wants to admit it.

It’s heartbreaking to see how this plays out. The same people who built the internet - open, collaborative, global - now preside over a system that locks out the very communities it was meant to serve. And yet, when you look at the numbers, the ITU is still the only thing standing between chaos and silence. We need reform, not resignation.

Seven year deadline is brutal. My buddy’s team missed it by 11 days. Lost their slot. No appeal. Just gone. Now they’re begging for a new one while Starlink rolls out 100 more sats a month

While it is true that the current regulatory architecture exhibits structural inequities, one must also acknowledge that the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, ratified by 114 nations, explicitly prohibits the appropriation of outer space resources. Therefore, any market-based allocation mechanism, however efficient, would constitute a violation of international law. The ITU’s framework, however imperfect, remains the sole legally defensible mechanism for spectrum and orbital allocation.

India tried to file for a satellite last year. Took us 2 years just to get our paperwork reviewed. Meanwhile, Elon Musk’s team files 500 slots in one day and the ITU says ‘cool’. This isn’t fair. This isn’t science. This is a game for the rich. We’re not asking for the moon - just a seat at the table.

Don’t forget the non-GSO loophole. Starlink’s 6k sats are in LEO, so they’re not hogging GSO slots. That’s why the ITU forced deployment milestones. Smart move. But now we need to fix the paper satellite backlog before it becomes a space traffic jam.

Let’s be real - the ITU is like a DMV run by astronauts. Slow, confusing, and somehow still the only place you can get a license. But hey, at least they don’t take bribes. Yet.

India has the technical capability. We have the engineers. But our government doesn’t prioritize space regulation like the U.S. or China. That’s not the ITU’s fault. That’s our failure. Stop blaming the system. Fix your own house first.