Every year, hundreds of satellites launch into Low Earth Orbit. Most of them are small, cheap, and built to last just a few years. But what happens when they stop working? If nothing is done, they become space junk-floating hazards that could collide with working satellites, trigger chain reactions, and turn our orbital neighborhood into a dangerous trash heap. That’s where drag sails come in.

Why We Can’t Just Let Satellites Float Forever

Space isn’t empty. It’s crowded. Over 10,000 active satellites are up there right now, and more than 30,000 pieces of debris larger than a softball are orbiting Earth. The problem isn’t just size-it’s speed. At 27,000 km/h, a 10-centimeter piece of debris can shatter a satellite like glass. The Kessler Syndrome-a cascading chain of collisions-is no longer science fiction. It’s a real risk we’re already seeing play out in slow motion. Regulations are catching up. NASA’s old rule said satellites must deorbit within 25 years. But in December 2023, the FCC made it clear: U.S.-licensed satellites must come down in five years. Other countries are following. If you’re launching a satellite today, you don’t have a choice-you need a plan to get it out of orbit safely. And for most small satellites, that plan is a drag sail.What Is a Drag Sail? (And Why It’s So Simple)

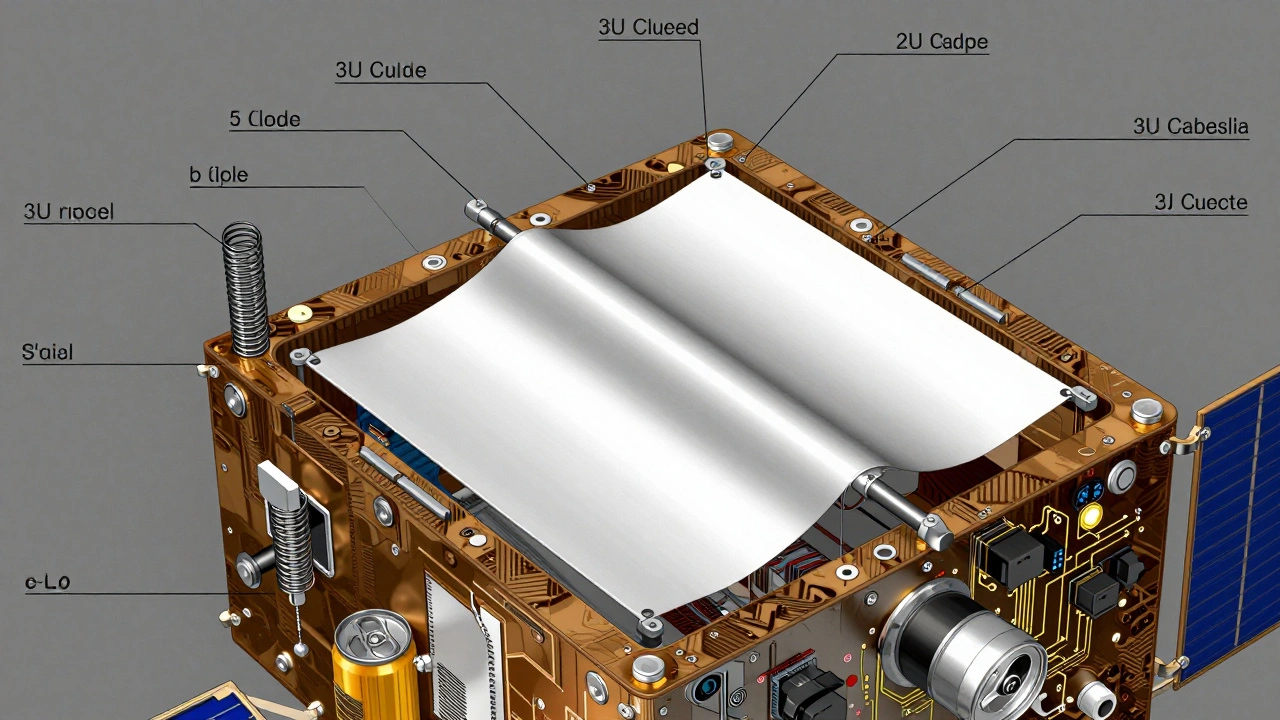

A drag sail is exactly what it sounds like: a big, thin sheet of material that unfolds in space to catch the last wisps of Earth’s atmosphere. Think of it like a parachute, but instead of slowing you down in thick air, it’s slowing you down in near-vacuum. The sail increases the satellite’s surface area without adding much mass. More surface = more drag. More drag = faster fall. Unlike rocket engines, drag sails need no fuel, no thrusters, no complex guidance systems. They’re passive. Once deployed, they work on their own. No commands. No power. Just physics. One of the first to prove this worked was CanX-7, a Canadian CubeSat launched in 2016. It carried a 4-square-meter sail made of ultra-thin CP-1 polymer-just 10 micrometers thick. Five years later, it burned up in the atmosphere. No explosions. No fragments. Just a clean exit. The math is simple. A satellite at 700 km without a drag sail might take 56 years to fall. With a sail, that drops to under 25 years. Some, like the Inflatesail mission, came down in just 72 days. That’s not luck-it’s design.How Drag Sails Actually Work

Drag sails work best below 1,300 km. Above that, the atmosphere is too thin to matter. That’s why they’re perfect for CubeSats and microsatellites, which mostly fly between 400 and 800 km. The sail is stowed tightly during launch-smaller than a soda can. Once the mission ends, a timer or ground command triggers the deployment. Spring-loaded booms unfold the sail like an umbrella. Materials like CP-1 are chosen because they’re lightweight, tough against atomic oxygen, and don’t build up static charge that could mess with electronics. A typical 3U CubeSat might use one or two sail modules. Larger satellites, like those in SpaceX’s Starlink fleet, use multiple units. The key metric is area-to-mass ratio: how much drag surface you have per kilogram of satellite. NASA and the FCC require a minimum of 0.0201 m²/kg to meet the 25-year rule. Most modern drag sails hit 0.05 or higher-way above the bar.

Why Drag Sails Beat Propulsion for Small Satellites

You might think: why not just use a tiny rocket to push the satellite down? It sounds logical. But here’s why it doesn’t work well for small satellites:- Propulsion adds weight-often 10-20% of the satellite’s total mass. That’s space and money lost for science or cameras.

- It needs fuel, tanks, valves, pumps. More parts = more things that can break.

- It requires precise orientation. A rocket burn needs the satellite pointed the right way. If your attitude control fails? The burn fails.

- It’s expensive. A small propulsion system can cost $50,000+. A drag sail? Under $10,000.

Who’s Using Drag Sails-and Why

It’s not just startups. The biggest players in space are using them:- SpaceX added drag sails to its Starlink Gen2 satellites to meet FCC rules.

- OneWeb and Amazon Kuiper both use them in their latest satellite designs.

- ESA’s CleanSpace program is investing $47 million in next-gen sails with self-healing materials.

- NASA requires them for all its small satellite missions.

Challenges and Limitations

Drag sails aren’t magic. They have limits.- Altitude cap: Above 1,300 km, they’re useless. Satellites in higher orbits need propulsion or tethers.

- Solar activity: When the sun is active, Earth’s atmosphere expands. That means more drag-and faster deorbit. During solar minimums, it can take longer. Operators have to plan for that.

- Stowage space: Even though they’re small, fitting a sail into a crowded 6U CubeSat can be a headache. One engineer on Reddit said it took up half a unit of space they needed for sensors.

- Material degradation: Early sails showed minor wear from atomic oxygen. Newer versions like CP-1 with UV coatings fix this.

The Future: Mandatory, Standardized, and Smarter

By 2027, the FCC’s 5-year rule will likely become global. The International Organization for Standardization is working on ISO 24113-5, a new standard to measure drag sail performance. That means every sail will be tested the same way-no more guesswork. Hybrid systems are coming. Tethers Unlimited’s KRAKEN robot arm can grab a dead satellite and attach a drag sail. That’s not just for new satellites-it’s for cleaning up old junk. And the Space Sustainability Rating, run by MIT and ESA, now gives bonus points to satellites with drag sails. Operators with higher ratings get priority for prime orbital slots. That’s a real financial incentive.What You Need to Know If You’re Building a Satellite

If you’re designing a CubeSat or microsatellite, here’s what to do:- Choose a drag sail early. Don’t wait until the end of design.

- Calculate your area-to-mass ratio. Aim for 0.05 m²/kg or higher to be safe.

- Use CP-1 or similar UV-resistant polymer. Avoid early inflatable designs-they’re outdated.

- Plan for stowage. Make sure your satellite has a dedicated 0.5U to 1U space for the sail mechanism.

- Test deployment on vibration tables. Launch shocks can jam the booms if not reinforced.

- Use a ground-commandable timer. Don’t rely on a single onboard clock.

Final Thought: Responsibility Isn’t Optional

We’ve spent decades launching satellites without thinking about the end. Now we’re paying the price. Space is not infinite. It’s not a dumping ground. And it’s not someone else’s problem. Drag sails are the simplest, cheapest, most reliable way to make sure our next generation of satellites doesn’t leave behind a trail of debris. They’re not flashy. They don’t make headlines. But they’re the quiet hero of responsible spaceflight. If you’re building a satellite today, you don’t have to be a genius to do the right thing. You just need to install a drag sail-and make sure it deploys.Do all satellites need drag sails?

No, but if they’re in Low Earth Orbit (below 1,300 km) and launched after 2024, they almost certainly need one. U.S. regulations require all licensed satellites to deorbit within five years. Drag sails are the most practical way for small satellites to meet that rule. Larger satellites in higher orbits may use propulsion or other methods.

Can drag sails work on satellites above 1,300 km?

No. Above 1,300 km, the atmosphere is too thin to generate meaningful drag. Drag sails are only effective in Low Earth Orbit. For satellites in higher orbits, like geostationary or medium Earth orbits, propulsion systems, electrodynamic tethers, or robotic servicing are the only viable deorbit options.

How long does it take for a drag sail to bring down a satellite?

It depends on altitude and solar activity. At 500 km, a sail can bring down a CubeSat in under a year. At 700 km, it typically takes 5-10 years. The Inflatesail mission came down in 72 days because it was deployed from a lower orbit. CanX-7 took five years from 700 km. Solar storms speed up the process by expanding the atmosphere.

Are drag sails safe? Do they break apart?

Yes. Drag sails are designed to burn up completely during reentry. The materials-like CP-1 polymer-are chosen specifically because they disintegrate without leaving fragments. Unlike explosive deorbit systems or broken satellites, drag sails don’t create new debris. They’re one of the safest end-of-life solutions available.

Can I buy a drag sail for my satellite project?

Yes. Companies like Vestigo Aerospace, Harken Space, and UTIAS-SFL sell ready-to-fly drag sail systems. Prices range from $5,000 to $20,000 depending on size and features. Many offer plug-and-play kits with mounting brackets, deployment mechanisms, and electrical interfaces that integrate easily into CubeSats and microsatellites.

What’s the difference between a drag sail and an electrodynamic tether?

Drag sails use atmospheric drag-no electricity needed. Electrodynamic tethers generate current by moving through Earth’s magnetic field, creating a force that slows the satellite. Tethers work at higher altitudes (up to 2,000 km) and can be controlled more precisely, but they’re more complex, require power, and have a higher risk of failure. Drag sails are simpler, cheaper, and more reliable for most small satellite missions.

Is there a standard size for drag sails?

No single size, but they’re designed by area-to-mass ratio. For a 3U CubeSat (about 4 kg), a 4 m² sail is common. Larger satellites need proportionally more sail area. The FCC and NASA require a minimum of 0.0201 m²/kg. Most modern sails exceed this, targeting 0.05-0.1 m²/kg for faster, more reliable deorbit.

12 Responses

Okay, but let’s be real-why are we even pretending this is new? Drag sails have been around since the 2010s, and we’re only acting shocked because the FCC finally enforced it? Someone’s gotta pay for all that junk we’ve been dumping for decades. And now, suddenly, it’s ‘responsible’? Please. It’s just damage control with a pretty name.

Drag sails are the bare minimum. We’re talking about orbital debris mitigation as if it’s a compliance checkbox. The real problem? We’ve normalized space as a free-for-all. No one’s auditing the 80% of satellites that don’t even *attempt* deorbit. This is theater. The FCC rule is a Band-Aid on a hemorrhage.

This is actually really encouraging. It’s not perfect, but it’s progress. Small satellites are the future, and if we can make them clean up after themselves, we’re building a better space environment for everyone. Keep pushing the tech forward.

It’s fascinating how we’ve anthropomorphized space as a ‘dumping ground’-as if the void has moral agency. But here’s the real question: if we treat space as a commons, why do we still rely on regulation to enforce stewardship? Shouldn’t responsibility be inherent, not incentivized by fines or slot priority? Drag sails are a tool, but the philosophy behind them… that’s what needs evolving.

So we’re spending $20k on a fancy piece of plastic to avoid paying $50k for a rocket? Sounds like a corporate budget hack. Honestly, just let ‘em burn. Who cares if it takes 50 years? Space is huge.

Look, I get the frustration with regulation. But this isn’t about red tape-it’s about legacy. Every satellite we launch is a promise. A promise that we won’t poison the orbit for the next team. Drag sails aren’t glamorous, but they’re honest. They don’t promise magic. They just… work. And sometimes, that’s enough.

Really appreciate the breakdown on materials-CP-1 with UV coating is a game-changer. I’ve seen too many early designs fail because they didn’t account for atomic oxygen degradation. Also, the 0.05 m²/kg target is spot on. Most teams underestimate how much surface area they need. Don’t skimp on the sail-it’s your insurance policy.

It is worth noting that the deployment mechanism reliability remains a critical factor. Even the most advanced sail design is ineffective if it fails to unfurl. Independent testing protocols should be standardized across all manufacturers. The absence of punctuated clarity in current documentation is concerning.

In India, we’ve seen how space tech can leapfrog legacy systems. Drag sails are the same-simple, scalable, cheap. No need for fancy rockets. Just physics and discipline. This is how the Global South can lead in sustainable space.

Wow a sail. So revolutionary. Next they'll tell us to recycle our coffee cups in orbit. Meanwhile China's got 500 satellites up there with zero deorbit plans. But hey, let's all feel good about our little plastic parachute

Just install it. Don’t overthink it. The math is clear. If you’re under 800 km and you’re not using a sail, you’re not just cutting corners-you’re gambling with other people’s missions. It’s not optional. It’s basic.

Drag sails? That’s a band-aid. Real American space leadership means propulsion. Real innovation means control. Letting a flimsy sheet of polymer do the work? That’s not innovation-that’s outsourcing responsibility. We built the moon landing. We don’t need to be passive about space.