When a satellite launches into orbit, it doesn’t just face vacuum and extreme temperatures. It’s bombarded by radiation that can fry circuits, flip memory bits, or cause total system failure. One faulty chip can kill a $1 billion mission. That’s why radiation testing standards aren’t optional-they’re the backbone of every serious space mission. These aren’t just guidelines. They’re non-negotiable rules that tell engineers exactly how to make sure every part on a spacecraft can survive what space throws at it.

What’s Bombarding Your Electronics?

Space isn’t empty. It’s filled with invisible energy that tears through silicon like a bullet through paper. There are three main sources: solar particles from the sun, trapped radiation in Earth’s Van Allen belts, and cosmic rays from deep space. These aren’t gentle showers. They’re high-energy protons, heavy ions, and gamma rays that can knock electrons loose, change transistor states, or permanently damage transistors. A single cosmic ray hitting a memory chip can flip a 0 to a 1. That’s called a single event upset (SEU). In a flight computer, that could mean wrong navigation data. In a life support system? Catastrophic.The Goal: Radiation Hardening

You can’t shield everything. Too much shielding adds weight, and weight means more fuel, more cost, less payload. So instead of wrapping everything in lead, engineers build parts that can take the hit. These are called radiation-hardened (RADHARD) components. They’re not just tougher. They’re designed from the ground up to resist damage. A RADHARD chip might use special silicon designs, protective oxide layers, or redundant circuits that can detect and correct errors on the fly. But you don’t just claim it’s hardened-you prove it. That’s where testing standards come in.Key Standards That Keep Satellites Alive

There’s no single global rulebook, but there are a few standards everyone in the industry respects. They come from NASA, the U.S. military, and Europe’s space agency. Each one covers different parts of the process.- MIL-STD-883 is the go-to for testing microelectronics. It doesn’t just check for radiation. It tests for humidity, temperature swings, vibration, and shock. If a part can survive this, it can survive launch and space.

- MIL-PRF-38534 and MIL-PRF-38535 focus on how hybrid circuits and integrated circuits are manufactured. They don’t just say “make it tough.” They say “here’s how to document every step, from raw materials to final test.”

- NASA-STD-8739.10 is the gold standard for NASA missions. It requires every electronic component to be tested under real space radiation levels and proven to work both during and after exposure. No exceptions. No shortcuts.

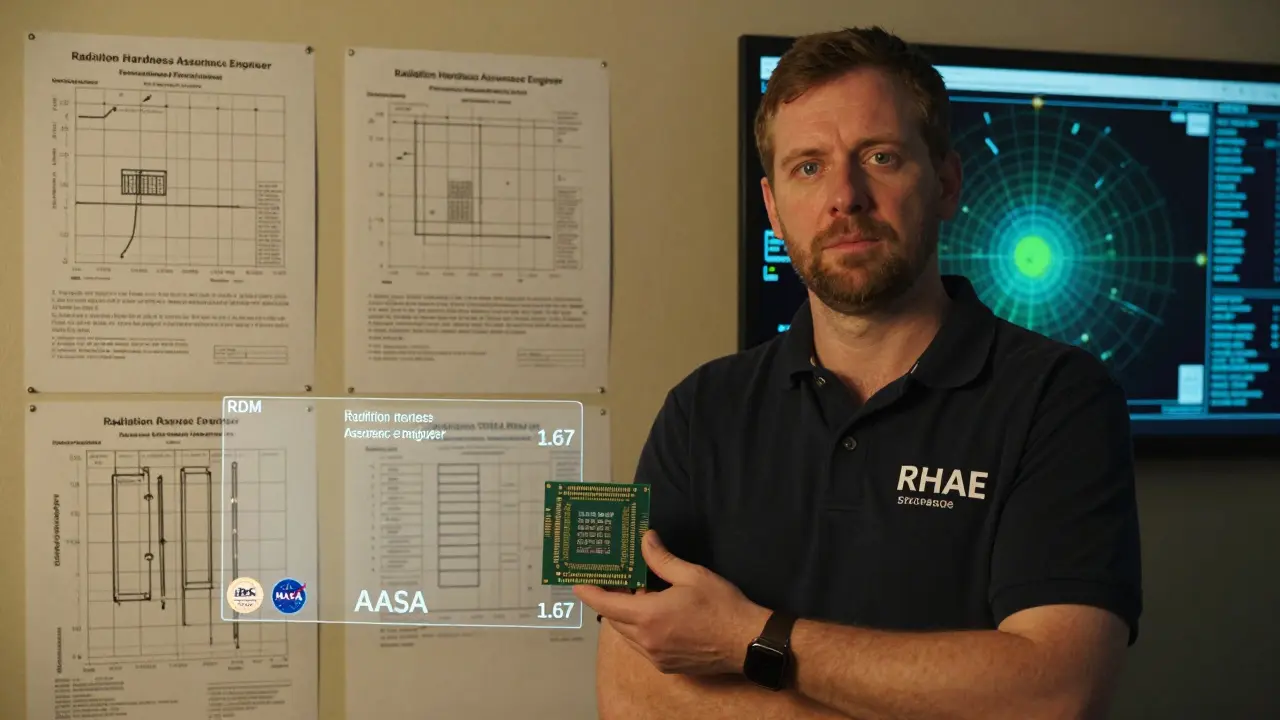

- ECSS-Q-ST-60-15C is Europe’s answer. Published in 2024, it’s the most up-to-date. It doesn’t just test parts-it requires a full Radiation Hardness Assurance (RHA) program. That means mapping the radiation environment, analyzing every component’s sensitivity, and proving there’s enough safety margin-called Radiation Design Margin (RDM)-before launch.

RDM is a simple idea: if a chip fails at 100 krad, and the mission expects 60 krad, your RDM is 1.67. That’s a 67% safety buffer. Most missions demand at least 1.5. Some, like deep-space probes, need 2.0 or higher.

Testing Methods: What You Actually Do

You can’t test radiation in a lab the same way you test a phone. You need particle accelerators. Facilities like ANSTO in Australia or the DMEA labs in the U.S. use proton and heavy ion beams to simulate space radiation. Here’s what they test for:- Total Ionizing Dose (TID): This is cumulative damage. It’s like leaving a chip in the sun for years. The test runs for hours or days, slowly ramping up radiation until the part fails. The goal? Prove it lasts longer than the mission.

- Single Event Effects (SEE): This is about sudden hits. They fire heavy ions directly at chips to trigger SEUs, latch-ups (SEL), or burnouts (SEB). Each test type has specific protocols. You don’t just say “we tested SEE.” You say “we used 60 MeV/u iron ions at 10^6 ions/cm² to test for SEU in SRAM.”

Documentation is critical. Every test must record: device model, test facility, beam type, energy, flux, duration, and pass/fail criteria. If another lab needs to replicate the test, they must be able to do it exactly.

What About Commercial Parts?

Here’s the twist: companies are now using car parts in satellites. Yes, you read that right. Automotive-grade chips from companies like Texas Instruments or Infineon are cheaper, more available, and sometimes more advanced than old military-grade parts. But they weren’t built for space. So engineers do something called upscreening. They take a commercial chip, then run it through the full MIL-STD-883 and NASA-STD-8739.10 tests. If it passes? It’s cleared for flight. This approach saves millions and speeds up development. But it’s risky. One bad batch, one overlooked failure mode, and you’re out of luck.Who Makes Sure It All Works?

Every major project has a Radiation Hardness Assurance Engineer (RHAE). This person doesn’t just run tests. They own the entire radiation safety plan. They work with designers to pick parts, with manufacturers to verify processes, and with mission planners to define the radiation environment. They’re the last line of defense. If the RHAE says “no,” the part doesn’t fly. Period.

Quality Isn’t Just About Parts

AS9100d isn’t about radiation. It’s about how you build things. It’s a quality management system that covers everything: how you train your staff, how you track materials, how you document changes. Two companies might use the same chip, but if one follows AS9100d and the other doesn’t, the difference in reliability can be huge. Space doesn’t forgive sloppy processes.The Future: More Parts, More Risk

As small satellites and constellations explode in number, the pressure is on. More launches mean more parts. More parts mean more testing. But testing is slow and expensive. The industry is pushing for better modeling-using software to predict failure instead of testing every chip. Monte Carlo simulations, AI-based failure prediction, and digital twins are emerging. But until they’re proven to match real-world results, physical testing still rules.Final Thought: It’s Not About Cost. It’s About Survival.

You could save $50,000 by skipping a radiation test. But if that one chip fails in orbit, you lose $100 million, years of work, and maybe even lives. The standards exist because people have learned the hard way. Every number, every test, every margin is there because someone once watched a satellite die because a part wasn’t ready. Don’t cut corners. Don’t guess. Follow the standards. Because in space, there’s no repair shop.What is Total Ionizing Dose (TID) testing?

TID testing measures how much cumulative radiation a component can absorb before it fails. It simulates long-term exposure in space by slowly exposing the device to gamma rays or protons in a controlled lab. The test continues until performance degrades beyond acceptable limits. Results are measured in rads or grays, and components must survive well beyond the mission’s expected dose.

What are Single Event Effects (SEE), and why do they matter?

SEE are sudden, random failures caused by a single high-energy particle striking a chip. They can flip a memory bit (SEU), trigger a short circuit (SEL), or destroy a transistor (SEB). Unlike TID damage, SEE happens instantly and unpredictably. A single event can crash a satellite’s computer. Testing for SEE requires particle accelerators and is mandatory for critical systems.

Can commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) parts be used in space?

Yes-but only after upscreening. That means subjecting COTS parts to full radiation testing under MIL-STD-883 and NASA-STD-8739.10. Many CubeSat and small satellite missions now use this approach to cut costs and access newer technology. However, it requires rigorous screening, statistical analysis, and redundancy planning. It’s not a shortcut-it’s a different path with higher risk.

What is Radiation Design Margin (RDM), and why is it important?

RDM is the safety buffer between the expected radiation dose in space and the dose at which a component fails. For example, if a chip fails at 150 krad and the mission expects 90 krad, the RDM is 1.67. Most missions require an RDM of at least 1.5. Higher margins are used for long-duration missions or critical systems. A low RDM means the part is operating too close to its limit-too risky to fly.

Who is responsible for radiation assurance on a space project?

The Radiation Hardness Assurance Engineer (RHAE) is the lead expert responsible for ensuring all electronic components meet radiation requirements. They define test plans, review test results, approve part selections, and validate the overall radiation design. Without an RHAE, a mission typically cannot proceed to flight qualification.

8 Responses

It’s wild to think that something as invisible as a single cosmic ray can end a billion-dollar mission. I’ve always been fascinated by how delicate our technology is out there-like a house of cards in a hurricane. The fact that engineers have to account for every possible failure mode, down to the atomic level, just blows my mind. And yet, we keep pushing farther, launching more satellites, relying on these tiny, fragile chips to hold everything together. It’s not just engineering; it’s a kind of quiet, relentless faith in human ingenuity.

Every time I read about radiation hardening, I think about how we’re basically asking machines to survive a warzone they never asked to be in. No wonder we need margins, redundancy, and layers of testing. It’s not about being paranoid-it’s about honoring the cost of what we’re trying to do.

Maybe someday we’ll have AI that predicts failures before they happen, but until then, I’m glad we still have people like RHAEs who refuse to cut corners. Because in space, there’s no do-over.

And honestly? I hope more young engineers read this. It’s not just technical-it’s philosophical. We build not just to survive, but to prove we can be responsible with the tools we’ve made.

Just a quick note: TID testing isn’t just about rads-it’s about how the degradation happens over time. A component might pass at 100 krad but fail at 150 krad because of cumulative lattice damage, not just gate oxide breakdown. That’s why accelerated testing uses controlled dose rates, not just total dose. Small detail, but it matters.

Oh, so now we’re using car parts in satellites? That’s… bold. I mean, I get it-cost, availability, performance. But let’s not pretend this isn’t Russian roulette with a 100 million dollar bullet. The fact that upscreening is even a thing tells you how much we’ve compromised.

And don’t get me started on AS9100d. It’s not just paperwork. It’s the difference between a mission that lasts 15 years and one that dies because someone didn’t log a change in a resistor’s supplier. I’ve seen it. I’ve cried over it. So yes, follow the damn process. Even if it’s tedious. Especially if it’s tedious.

China and Russia don’t follow these standards. Their satellites last longer. We’re overcomplicating everything. Just build tough. No need for 1.67 RDM. We’re the best. End of story.

As someone from Canada, I’ve always admired how the U.S. and Europe lead in space standards-but we’re starting to catch up. CSA’s work on RADHARD for the Canadarm3 and lunar missions is quietly impressive. We don’t shout about it, but we’re doing the math. And yeah, we use COTS parts too. But we test them like they’re going to Mars. Because they might be.

Also, the fact that ECSS-Q-ST-60-15C came out in 2024? That’s progress. We’re not stuck in the 90s anymore. It’s about time.

So let me get this straight: we spend $50M testing a chip so it doesn’t flip a bit… but we still let a $200 Amazon Echo chip fly on a CubeSat because ‘it passed upscreening’? Huh. Guess that’s the future. The future where we gamble with orbits and call it innovation.

At least we have RHAEs. The unsung heroes in lab coats, staring at oscilloscopes while the whole world forgets they exist. Cheers to them. And to the cosmic rays that still win sometimes.

It is with profound respect and deep admiration that I acknowledge the meticulousness and unwavering discipline inherent in the Radiation Hardness Assurance protocols. In an era where expediency is often mistaken for progress, the adherence to standards such as NASA-STD-8739.10 and ECSS-Q-ST-60-15C represents not merely technical excellence, but a moral imperative. The lives-human and institutional-that depend upon these safeguards must never be treated as collateral. One must not merely comply; one must reverence the process. For in the silence of the void, only precision speaks.

Okay, but have you SEEN the paperwork? I mean, really. The spreadsheets. The 47-page test logs. The signatures. The NOTARIZED signatures. I once saw a guy cry because a capacitor’s lot number was written in pencil instead of ink. I’m not joking. I’m not even exaggerating. This isn’t engineering-it’s performance art. And the audience? A bunch of dead satellites in geostationary orbit, silently judging us.

But hey-if you’re gonna die in space, you might as well die with a fully documented, ISO-compliant, 1.8 RDM-approved chip. That’s just how we roll.