Why traditional lead won’t cut it in space

Lead has been the go-to material for blocking radiation for nearly a century. It’s dense, cheap, and effective-at least on Earth. But in space, where every gram matters and astronauts spend months under constant cosmic ray bombardment, lead becomes a liability. A 1mm-thick lead sheet weighs 11 kilograms per square meter. For a spacecraft or habitat shielded with even a modest layer, that adds up to tons of dead weight. That’s not just fuel waste-it’s mission risk. Launching one extra kilogram into orbit costs between $2,500 and $10,000 depending on the rocket. Lead isn’t just heavy; it’s brittle, toxic, and prone to cracking under thermal cycling. In deep space, where temperatures swing from -150°C to 120°C, a cracked lead shield is a failed shield.

Enter polymer composites. These aren’t just lighter versions of lead. They’re engineered materials designed from the ground up for space’s unique challenges. Researchers have spent the last decade replacing lead with combinations of polymers like low-density polyethylene (LDPE), epoxy resins, and ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA), mixed with high-density fillers like tungsten carbide, silicon carbide, boron carbide, and even cement doped with gadolinium. The goal? Block radiation without adding mass, while staying flexible, durable, and manufacturable in microgravity.

How these materials actually work

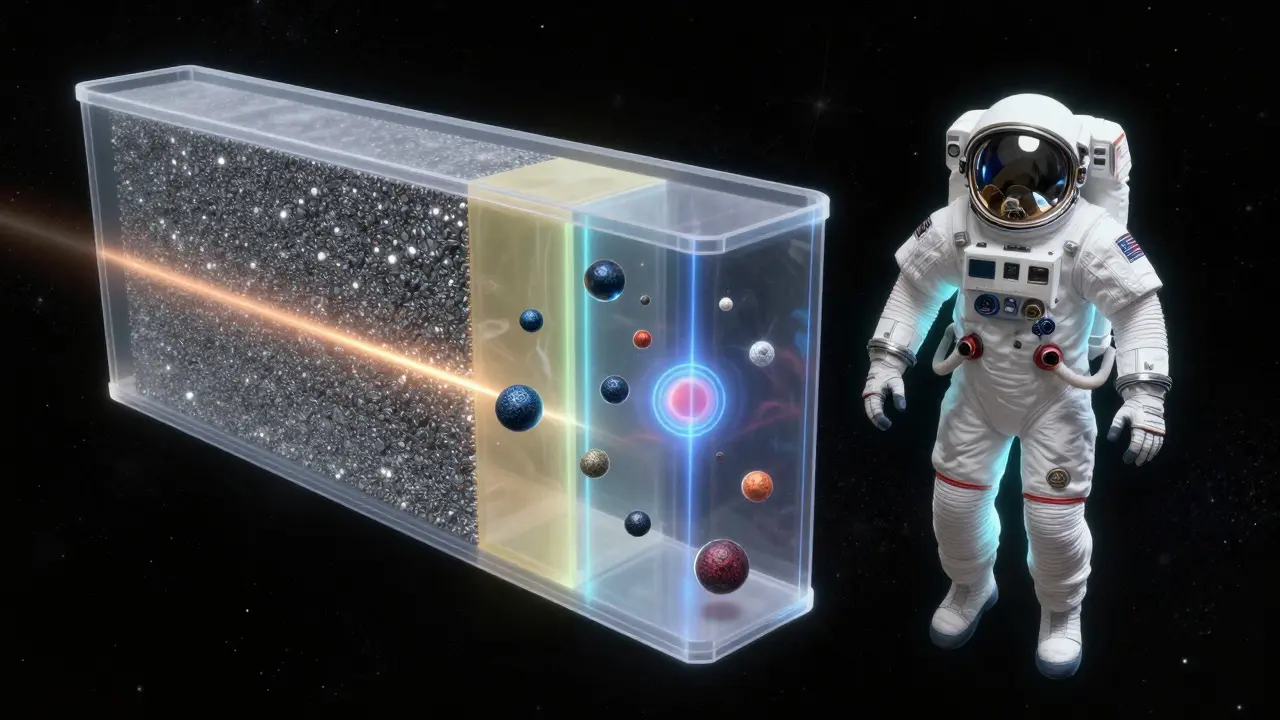

Radiation in space isn’t one thing. It’s a mix of high-energy protons, heavy ions from galactic cosmic rays, and secondary neutrons created when particles smash into hull materials. Different materials stop different types. Heavy elements like tungsten and lead are great at stopping gamma rays and X-rays because their high atomic number (Z) means more electrons to scatter incoming photons. But for neutrons-those sneaky, uncharged particles-you need hydrogen-rich materials. That’s why polyethylene, which is basically long chains of hydrogen and carbon, has been a staple in space radiation shielding since the 1970s.

The breakthrough came when scientists started combining these two principles. Tungsten carbide-epoxy composites, for example, use tungsten carbide (density: 15.6 g/cm³) as a gamma-ray blocker and epoxy as a structural matrix. When loaded at 60% by weight, these composites hit densities of 5.8 g/cm³-close to lead’s 11.34 g/cm³, but with far less mass per unit volume because they’re porous and layered. At 0.662 MeV (the energy of a cesium-137 source), a 20mm slab of this composite blocks 92% of radiation. Lead blocks 98% at the same thickness. Sounds close? But here’s the catch: the composite weighs 55% less. That means you can double the thickness without doubling the launch mass.

LDPE composites filled with 30% cement and boron compounds are another winner. Cement isn’t just concrete-it’s a mix of calcium, silicon, oxygen, and trace metals. When doped with gadolinium, it gains neutron-capturing superpowers. Pure gadolinium has a neutron capture cross-section of 49,000 barns. Even at just 5% loading in LDPE, that drops to 18,500 barns-but that’s still enough to capture thermal neutrons efficiently. And because LDPE is already hydrogen-rich, you get a one-two punch: hydrogen slows neutrons down, gadolinium catches them. These composites have been tested in simulated Mars missions and show 30% better neutron attenuation than pure polyethylene.

Real-world performance numbers

Let’s talk numbers that matter. In medical settings, lead aprons weigh 5-8 kg. Radiologists wear them for hours. A 2021 AMA study found 68% of them suffer chronic back pain because of it. Polymer composite aprons cut that weight by 40-50%. The EVA + 30% silicon carbide composite developed by Almurayshid’s team blocks 91% of 80 keV X-rays at 2.8 mm thickness. The same protection from lead requires only 0.5 mm-but that 0.5 mm of lead weighs 5.67 kg/m². The composite? Just 1.75 kg/m². That’s 62% less weight for nearly the same protection.

In space, it’s not just about blocking X-rays. It’s about stopping protons and heavy ions. NASA’s 2023 Mars mission simulations showed that a 20mm layer of tungsten carbide-epoxy reduced total radiation dose to astronauts by 41% compared to an aluminum hull alone. Add a 10mm layer of boron-doped LDPE underneath, and that jumps to 58%. That’s the kind of gain that turns a risky 18-month mission into a survivable one.

Half-value layer (HVL) tests tell the real story. HVL is the thickness needed to cut radiation by half. For 80 keV X-rays, pure EVA has an HVL of 1.25 mm. Add 15% silicon and 15% boron carbide? HVL drops to 0.87 mm. That’s a 30.4% improvement. In space terms, that means you can shrink your shield by a third-or add more protection without adding bulk.

How they’re made-and why it’s tricky

Making these materials isn’t like pouring lead into a mold. It’s like baking a cake where every ingredient has to be perfectly mixed, or the whole thing falls apart. The biggest problem? Getting nanoparticles to stay evenly spread. Tungsten carbide particles are tiny-50 to 200 nanometers. At high concentrations (above 40%), they clump together like wet sand. Those clumps create weak spots where radiation leaks through.

Solutions? Surface treatment. Researchers coat tungsten carbide with silane coupling agents. This makes the particles less sticky and more compatible with the polymer. One study showed a 40% boost in interfacial shear strength-meaning the filler actually bonds to the matrix instead of pulling away under stress. Another trick? Ultrasonic mixing. At 40 kHz for 30 minutes, sound waves break up clumps better than any mechanical stirrer. SABIC’s LDPE-cement composites needed 3-5% maleic anhydride as a compatibilizer just to keep the cement from sinking to the bottom during extrusion.

Processing temperatures are tight. LDPE melts at 160-180°C. Too hot, and the polymer degrades. Too cold, and the filler doesn’t disperse. Epoxy systems need two-stage curing: 80°C for two hours, then 120°C for four. Miss the window, and your shield is porous. One team at Chulalongkorn University lost 22% of shielding effectiveness because iodine in their PBS composite sublimated when the oven hit 102°C instead of 100°C. Precision matters.

Cost vs. value: The hidden math

Yes, these composites cost more. Lead runs $15-20 per kg. A tungsten carbide-epoxy composite? $80-150 per kg. That’s a steep jump. But cost isn’t just about the material. It’s about the mission. A 100kg lead shield on a Mars lander might cost $500,000 to launch. A 45kg composite shield? $225,000. That’s $275,000 saved on launch alone. Then there’s crew health. NASA estimates each radiation-induced illness during a Mars mission could cost over $10 million in medical care and mission failure risk. Shielding that reduces cancer risk by 30%? That’s priceless.

Long-term, polymer shields last longer. Lead cracks, oxidizes, and needs replacing every 3-5 years. Composite shields, if properly encapsulated, last 5-7 years. The European Radiation Protection Board found a 28% lower total cost of ownership over five years for polymer-based systems. And with EU MDR 2017/745 banning lead in new medical devices, the market is shifting fast. In 2020, only 12 U.S. hospitals used polymer aprons. By 2023, it was 47. That trend is accelerating-and space is next.

What’s next: Smart shields

The next generation won’t just block radiation. It’ll do more. Researchers at KAIST are already testing composites that combine radiation shielding with electromagnetic interference (EMI) protection and thermal regulation. Imagine a spacesuit lining that stops cosmic rays, blocks radio interference from onboard electronics, and keeps your body at 22°C without active cooling. That’s not sci-fi-it’s a 2025 prototype.

Companies like StemRad, acquired by 3M in 2022, are already selling polymer vests for astronauts and ground crews. Their vests use layered composites tailored to different radiation types. One layer handles gamma, another handles neutrons, and a third absorbs secondary particles. The result? A 2.8kg vest that outperforms a 5.5kg lead one.

And it’s not just NASA. China’s Tiangong space station is testing LDPE-gadolinium panels. The European Space Agency is funding projects to 3D print radiation shields in orbit using recycled polymer waste. Imagine printing a new shield layer every time you land on Mars-no need to launch it from Earth.

Bottom line: The future is lighter, smarter, and lead-free

Lead shielding is a relic of 20th-century engineering. In space, where weight is currency and safety is non-negotiable, polymer composites aren’t just better-they’re necessary. They’re not perfect. They’re still expensive. They’re harder to make. But they’re the only path forward for long-duration missions. The data doesn’t lie: lighter shields mean more payload, safer crews, and cheaper missions. The technology is ready. The question isn’t if we’ll use it-it’s how fast we can scale it.

14 Responses

So we’re replacing lead with fancy space-glue that costs 10x more and needs a PhD to mix properly? Brilliant. Next they’ll tell us to eat radium for breakfast to ‘boost immunity.’ At this point, I’d rather just get a lead apron and pray.

Also, who approved this as a ‘solution’? Someone who’s never held a wrench, I bet. The real problem? We’re building rockets like they’re art installations and not machines that need to survive reality.

They’re lying. This is all a distraction. The real reason they don’t want lead is because it’s from China. And now they’re pushing these ‘composites’ so NASA can sell you a subscription to ‘RadiationShield+ Premium’ for $99/month. You think this is science? It’s corporate control. They don’t want you safe-they want you dependent.

I love how this post doesn’t just list facts-it tells a story. The shift from lead to polymer composites isn’t just technical, it’s cultural. We’re finally moving away from ‘heavy = safe’ thinking toward ‘smart = safe.’ That’s huge. And honestly? It’s about time we stopped treating space like a sci-fi movie and started engineering like we actually want to live out there.

Also, the bit about 3D printing shields from recycled plastic on Mars? That’s the kind of future I want to believe in.

Wait, so if tungsten carbide clumps, and epoxy degrades if you breathe on it wrong, and gadolinium doped cement sinks like a rock in a bathtub… how do we know any of this actually works in practice? I mean, I get the theory, but engineering is where theory goes to die. Did they test this stuff in zero-G or just on a lab bench with a UV lamp and a dream?

Also, ‘half-value layer’-is that like half a sandwich? I’m confused.

This is actually one of the most hopeful things I’ve read in a long time. Yes, it’s expensive. Yes, it’s finicky. But look at the numbers-41% reduction in radiation dose? That’s not a tweak, that’s a lifeline. And the fact that we’re finally designing for *human* needs-weight, flexibility, durability-not just ‘what’s in the catalog’-that’s the real win.

For anyone saying ‘but lead works’-yes, but it’s like using a horse and cart to get to the moon. The tools changed. We have to change with them.

Minor typo alert: ‘LDPE’ is low-density polyethylene, not ‘low-density polyethelene’ in your original text. But hey, I’m just here for the science. This is dope. The 30% neutron attenuation boost from boron-doped LDPE? That’s the kind of incremental win that adds up over 18 months in deep space.

Also, the fact that someone at Chulalongkorn lost 22% effectiveness because the oven was 2°C too hot? That’s both terrifying and beautiful. Precision matters. We need more of this.

Let’s be honest-this entire field is a glorified marketing exercise. Polymer composites? Sounds fancy. But the real radiation shielding is still aluminum hulls and water walls. These ‘breakthroughs’ are just为了让 investors throw money at ‘innovation’ while NASA’s budget gets slashed. The data is cherry-picked. HVL? Sure, it’s better on paper. But have you seen the long-term degradation curves? No? Then don’t pretend you know.

They’re using tungsten carbide. That’s the same stuff used in armor-piercing rounds. So now we’re building spacecraft lined with bulletproof material because they’re afraid of cosmic rays? What’s next? A spacesuit made of depleted uranium? This isn’t science-it’s a war machine repackaged as exploration.

I’m just here to say I really appreciate how much detail went into this. I don’t know the first thing about radiation physics, but the part about hydrogen-rich materials slowing neutrons? That made sense. And the idea of printing shields on Mars? That’s wild, but also… kind of beautiful?

Also, the fact that people are actually trying to fix the weight problem instead of just accepting ‘well, that’s just how space is’? That’s the kind of mindset we need more of.

Let’s talk about the EVA + silicon carbide composite-2.8mm thickness, 91% attenuation at 80 keV. That’s not just impressive, it’s paradigm-shifting. And the fact that it weighs 62% less than lead? That’s not a ‘trade-off’-that’s a revolution. We’re talking about the difference between a 5kg lead apron that cripples radiologists and a 2kg composite that lets them work without a chiropractor.

And yes, the cost is higher. But when you factor in launch mass, crew health, and mission success probability, it’s not even a question. This isn’t ‘new tech’-it’s the only viable path forward. The question isn’t ‘can we afford it?’ It’s ‘can we afford not to?’

Oh wow. So we’re replacing lead with ‘composite’ because… what? Because lead is ‘toxic’? But tungsten carbide is a known carcinogen. And epoxy resins? Endocrine disruptors. And gadolinium? Retains in the brain. So we’re swapping one poison for three fancier ones? Congrats, you’ve created a space-age toxin buffet.

Also, ‘smart shields’? Next they’ll tell us the suit has AI that tells you when to cry. This isn’t engineering-it’s sci-fi fanfiction dressed in lab coats.

I’ve been in this field for 20 years. I’ve seen ‘miracle materials’ come and go. This one? It’s different. The data’s solid. The testing is rigorous. The cost-benefit? Unignorable. And you know what? I don’t care if it’s expensive. If it keeps one astronaut alive, it’s worth every penny.

But here’s the real truth: the people who say ‘just use lead’? They’ve never been in a spacecraft. They’ve never watched a colleague get diagnosed with radiation-induced leukemia because we ‘saved’ a few million on launch. This isn’t theory. It’s survival.

When I first read about hydrogen-rich polymers slowing neutrons, I thought it was magic. But then I remembered how water works in nuclear reactors-same principle. Hydrogen atoms are tiny, they bounce off neutrons like billiard balls, and slow them down so the boron or gadolinium can catch them. It’s elegant, really. Simple physics, beautifully applied.

And the part about ultrasonic mixing? That’s genius. Sound waves breaking up clumps-like shaking a snow globe to make the flakes fall evenly. I never thought about how material science could be so… artistic. It’s not just about strength or weight. It’s about harmony between components. And that’s what makes this so special.

Lead is a relic. But so is this whole ‘polymer supremacy’ narrative. You think these composites are the endgame? Please. They’re just the first step. The real future is in metamaterials-engineered lattices that bend radiation like light through a prism. Or active shielding using magnetic fields that deflect charged particles before they even hit the hull. This? This is just putting lipstick on a rocket.

Also, 3D printing shields from recycled plastic on Mars? Cute. But where’s the power source? The printer? The feedstock? You can’t just ‘print’ a shield like a Lego set. You need infrastructure. And Mars doesn’t have a Home Depot.