When we think of space travel, we picture weightlessness, stunning views of Earth, and the thrill of exploration. But beneath the glamour lies a silent, invisible threat: radiation. For astronauts heading beyond low Earth orbit-especially to Mars-it’s not just about surviving the journey. It’s about surviving the long-term consequences. And right now, NASA’s rules say: 600 millisieverts is the max any astronaut can absorb in their entire career. That’s it. No exceptions. No matter your age, gender, or health. But here’s the problem: a Mars mission could expose a crew to over 1,000 millisieverts. So who gets to decide if that’s okay?

How Much Radiation Is Too Much?

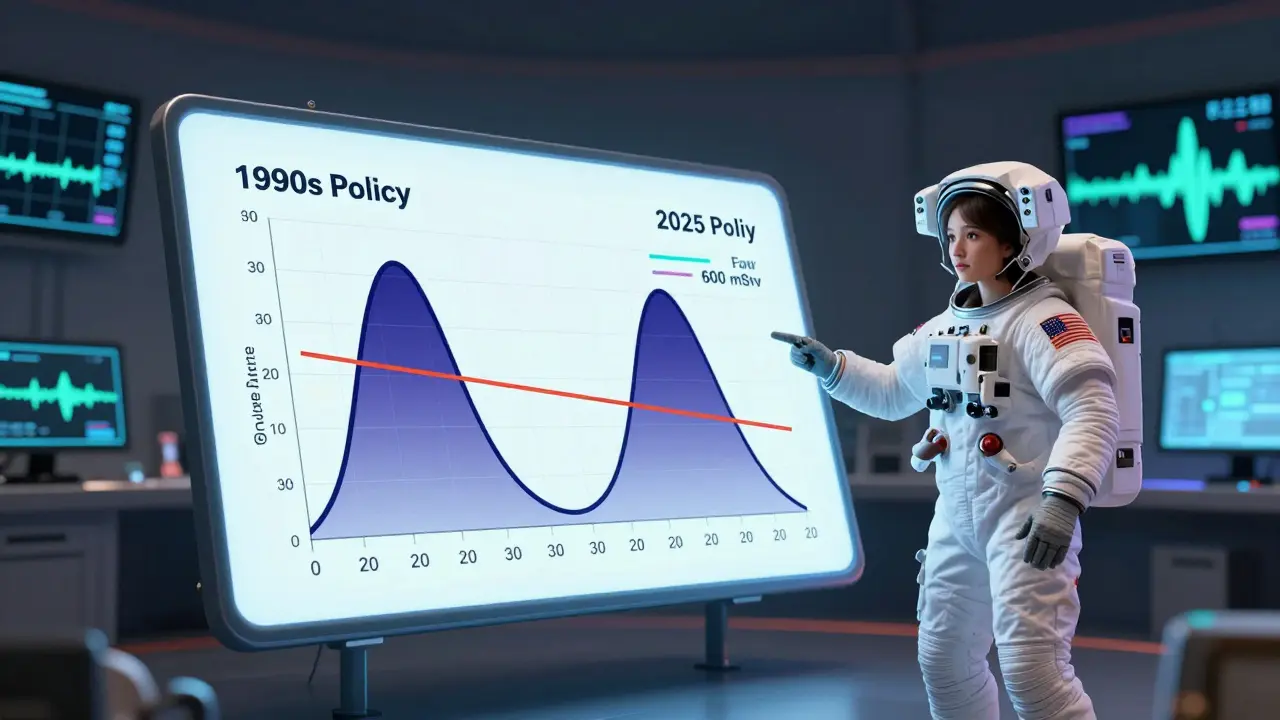

Back in the 1990s, NASA let radiation limits vary by age and sex. A 30-year-old woman could only take about 180 mSv over her career. A 60-year-old man? Nearly 700 mSv. Why? Because younger people, especially women, have higher lifetime cancer risks from radiation. It made sense. But in June 2025, NASA scrapped that. Now, everyone gets the same cap: 600 mSv. No more personalization. No more math based on biology. Just one number for everyone.

Let’s put that in context. A six-month trip to the International Space Station? Around 100 mSv. That’s like getting 100 chest X-rays every day for 180 days. Now imagine a Mars mission: 18 to 24 months total. That’s not 100 mSv. It’s 400 to 800 mSv-maybe more. And that’s without even counting solar storms, which can dump 250 mSv in a single day. NASA’s limit for those events is 250 mSv per storm. One storm could eat up half your lifetime allowance.

So what happens if you’re selected for a Mars mission? You’ll hit the 600 mSv limit before you even leave Earth orbit. That’s not a bug. It’s a feature of the current policy. NASA admits it. They’ve asked the National Academies of Sciences to figure out if this is ethically acceptable. In other words: we’re sending people on missions that break our own rules. And we’re asking if that’s okay.

The Shielding Problem

You can’t just wrap a spaceship in lead. It’s not that simple. Galactic cosmic rays-high-energy particles from deep space-are so powerful, they punch through most materials. Worse, when they hit shielding, they break apart and create secondary radiation. More shielding = heavier ship = more fuel needed = more cost. And right now, we don’t have the rockets to carry a ship thick enough to make a real difference.

Some engineers are trying active shielding: magnetic fields that deflect radiation like Earth’s magnetosphere. Others are testing water walls, polyethylene panels, even hydrogen-rich plastics. But none of it works perfectly. A ship with enough shielding to cut exposure by half might weigh twice as much as what we can launch. That means fewer supplies, less science, longer trips. It’s a trade-off no one wants to make.

Then there’s nuclear propulsion. If we could cut Mars transit time from 9 months to 4, we’d slash radiation exposure by 30-40%. But nuclear engines bring their own risks: radiation from the reactor itself. One study showed a nuclear-powered ship might save 135 mSv in space radiation but add 150 mSv from the engine. Net gain? 15 mSv. Still within limits. But only if you’re okay with having a mini-nuclear reactor on board. And if something goes wrong? No emergency room in space.

Who Decides? The Ethics of Consent

Here’s the most uncomfortable question: Do astronauts really choose this?

NASA says yes. They require informed consent. But what does that mean? Astronauts are trained to be tough. To push through danger. To serve the mission. How many truly understand that their lifetime cancer risk might jump from 20% to 35%? Or that radiation can damage their nervous system, eyesight, or even their heart? These aren’t just numbers. They’re futures.

And what about individual differences? Two astronauts might have the same age and fitness level, but one has a genetic marker that makes them 3x more sensitive to radiation. Should they be allowed to opt out? Or should they be forced to take the same risk as everyone else? Right now, NASA doesn’t test for this. It’s not required. So they’re making decisions based on averages-averages that don’t reflect real people.

There’s also the question of waivers. Should a 50-year-old astronaut, with only a few years left before retirement, be allowed to exceed the 600 mSv limit? After all, their cancer risk is lower. But if we allow one waiver, do we open the door for others? Do we start normalizing risk? And what pressure does that put on younger astronauts who don’t want to be seen as "too cautious"?

The Policy Gap

NASA’s current rules were designed for low Earth orbit. They don’t fit deep space. That’s why the agency is now working on a new framework for Mars missions. It’s called an "exploration-class" standard. It would allow higher exposures-but only if:

- The astronaut gives fully informed, documented consent

- There’s enhanced long-term health monitoring after the mission

- There’s independent ethical review before launch

- And the exposure is still kept as low as reasonably achievable (ALARA)

This isn’t about lowering standards. It’s about recognizing that different missions need different rules. You don’t treat a 10-day shuttle flight the same way you treat a 3-year Mars expedition. The problem? No one has agreed on what those new limits should be. The National Academies are still reviewing it. The public hasn’t weighed in. And astronauts? They’re still flying under old rules for new missions.

What’s Next?

The science is moving faster than the policy. We know more about space radiation now than ever before. We’ve mapped out the biological effects. We’ve modeled the risks. But policy lags. And ethics hasn’t caught up.

Real progress will come when we stop treating astronauts like test subjects and start treating them like partners. That means:

- Personalized risk assessments using genetic screening

- Transparent, ongoing communication-not just one consent form before launch

- Independent ethics panels with bioethicists, not just engineers

- Clear rules on waivers: who can request them, under what conditions

- Long-term health tracking for life, not just 10 years after landing

And we need to stop pretending we can shield our way out of this. The answer isn’t just better materials. It’s better decisions. Better conversations. Better respect for the human cost of exploration.

Space isn’t a game. It’s not a competition. It’s not about planting flags. It’s about sending people into an environment that can permanently damage their bodies-and asking them to sign a waiver before they go. That’s not bravery. That’s a policy failure. And if we don’t fix it, we’re not exploring space. We’re just risking lives for headlines.

Why did NASA change from age- and sex-based radiation limits to a universal 600 mSv cap?

NASA switched to a universal 600 mSv limit in June 2025 to simplify policy, reduce administrative complexity, and avoid potential discrimination based on gender or age. The previous system, which allowed older men higher limits than younger women, was based on cancer risk models that assumed women had higher lifetime susceptibility. But critics argued this created unequal treatment under the law and didn’t account for individual health variation. The new standard uses a 35-year-old female as the reference model, which is more conservative, and applies it equally to everyone-regardless of personal risk profile.

Can astronauts refuse a Mars mission because of radiation risks?

Yes, astronauts can refuse a mission for any reason, including radiation concerns. NASA doesn’t force anyone into a mission they’re uncomfortable with. However, the culture of spaceflight often pressures astronauts to volunteer, especially for high-profile missions. Refusing might affect future assignments or career progression. While policies require informed consent, they don’t always guarantee psychological safety in saying no. Some astronauts have reportedly turned down Mars mission training because they didn’t feel the risks were fully disclosed.

Are there any medical tests that can predict how an astronaut will respond to space radiation?

Currently, no tests can reliably predict individual radiation sensitivity. NASA doesn’t screen astronauts for genetic markers linked to radiation susceptibility, such as BRCA1 or ATM mutations, because those tests aren’t standardized for space environments. Some research labs are studying DNA repair efficiency and biomarkers, but nothing is used in operational decision-making yet. This means two astronauts with identical health profiles could have vastly different cancer risks from the same exposure-and NASA wouldn’t know.

What happens to astronauts after they return from deep space missions?

Post-mission health monitoring is required, but it’s limited. NASA tracks cancer incidence, cardiovascular health, and vision changes for decades, but there’s no dedicated long-term registry for space radiation survivors. Many astronauts receive annual checkups, but follow-up care depends on their home country’s healthcare system. For U.S. astronauts, NASA provides lifetime medical monitoring, but it doesn’t cover all potential late-onset effects. There’s no guarantee of treatment for radiation-induced illnesses that appear 20 or 30 years later, especially if they’re not classified as service-connected.

Is there a legal or international framework governing radiation exposure in space?

No. There’s no international treaty or binding law that sets radiation exposure limits for astronauts. NASA’s standards are internal policy, not global law. Other space agencies like ESA, Roscosmos, or CNSA use different limits or no formal limits at all. The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 says nations are responsible for their astronauts’ safety, but it doesn’t define what "safety" means in radiation terms. This creates a patchwork of rules where one country’s acceptable risk is another’s violation. Without global consensus, there’s no real accountability.

15 Responses

I just can't wrap my head around this. They send people to Mars with a cap that's already exceeded before launch. It's not bravery. It's a system that's broken. And we call it progress?

Simple math: if the limit is 600 and the mission is 800, we're not preparing for space-we're preparing for sacrifice.

I mean… wow.

Just… wow.

They’re sending humans into space with a policy that was made for a different century. Like, imagine if your car had a speed limit of 60 mph… but the highway’s built for 120. And then they say ‘you’re fine, just don’t complain.’

And the worst part? We’re not even talking about the kids who’ll grow up with parents who might never come home. Or come home… broken.

Oh please. This isn't a tragedy. It's a logistical headache wrapped in a moral panic. NASA's not murdering astronauts. They're just not coddling them. You think astronauts are signing up for spa days? No. They're signing up to be the first idiots to walk on Mars. And if you're gonna be first? You better be ready to take the heat. Or the radiation. Or both.

Also, genetic screening? Next you'll want DNA-based mission assignments. Soon we'll have astronauts with different colored helmets based on their BRCA status. Get real.

There’s a deeper silence here. Not the silence of space. But the silence of consent. We ask people to sign papers like they’re agreeing to a gym membership. But what is consent when the alternative is career suicide? When your peers are already training? When your name is on the wall next to Armstrong and Aldrin?

We don’t consent. We perform consent. And that’s the real tragedy. Not the radiation. The theater.

I believe we can do better. Space exploration should not come at the cost of human dignity. Personalized risk assessments, transparent communication, and long-term health tracking aren’t luxuries-they’re necessities. Let’s not rush into Mars because we’re excited. Let’s go because we’re responsible.

There’s a difference between courage and recklessness. We must choose wisely.

Lmao so now we're worried about radiation? What about the microgravity? The bone loss? The muscle atrophy? The psychological toll? The isolation? The fact that if you sneeze wrong in space you might float into a valve? We're fixating on ONE risk like it's the only one that matters. You're all drama queens. Radiation's been studied for 60 years. We're not flying blind here.

Also, 'nuclear engine adds 150 mSv'? That's not even a full chest CT. Chill.

Wait so if I'm a 25-year-old woman and I get picked for Mars… I'm basically being told I can't have kids? Because of some 1990s study? That's wild. I mean… what if I just really wanna go? Shouldn't I get to decide? Why is the government deciding for me? It's like they're saying 'you're too fragile' while also saying 'you're tough enough to go to Mars'. Which is it??

I think the real issue isn't the number. It's the lack of conversation. We treat astronauts like machines with a radiation tolerance threshold. But they're people. With families. With fears. With dreams. Maybe the solution isn't more shielding. Maybe it's more honesty. More listening. More time to talk before they sign anything.

Oh sweet mercy. Let me get this straight. We’re asking astronauts to risk their lives, but we won’t even test their DNA because ‘it’s not standardized’? And then we act shocked when someone gets cancer 15 years later? You people are the reason we need a new ethics committee. Every. Single. Time.

And let’s be real-this isn’t about science. It’s about PR. NASA doesn’t want to look like they’re discriminating. So they just pretend everyone’s the same. Meanwhile, one astronaut’s BRCA1 mutation is quietly being ignored. And no one’s talking about it. Because it’s easier that way.

The fundamental flaw in contemporary space policy is its failure to recognize that ethical frameworks must evolve alongside technological capability. The 600 millisievert cap, while administratively convenient, is a relic of a pre-deep-space era. It assumes homogeneity where none exists. It substitutes uniformity for justice. It replaces individual autonomy with bureaucratic conformity. When a governing body mandates a single exposure limit for a population whose biological susceptibilities vary by orders of magnitude, it does not enforce safety-it enforces ignorance. True ethical stewardship requires not just informed consent, but individualized risk assessment, longitudinal biomonitoring, and the institutionalization of bioethical review boards independent of aerospace engineering priorities. Anything less is not policy. It is negligence dressed as pragmatism.

I read this whole thing. Took me 20 minutes. Honestly? I’m impressed. Most of the time these posts are just rage posts. But this one? It’s clear. Thoughtful. The part about nuclear engines adding radiation… I didn’t know that. I thought shielding was the whole problem. Turns out the solution might be part of the problem. Wild.

Anyway. I hope they start testing DNA. Not because it’s cool tech. But because it’s fair.

This whole article is just a cry for attention. Like, wow, radiation is dangerous? Newsflash: everything in space is dangerous. Gravity, isolation, silence, confinement, equipment failure, micrometeorites, psychological breakdowns. Radiation is just one of them. And now we’re treating astronauts like they’re fragile porcelain dolls? They’re the toughest people on the planet. They don’t need coddling. They need a mission. And if they’re smart enough to volunteer? Then they’re smart enough to take the risk.

Also, 600 mSv? That’s less than half of what Chernobyl cleanup workers got. And they didn’t get a medal. They got cancer. So what’s the difference? Oh right-space is pretty. That’s the only reason this is a ‘crisis’.

We have forgotten that exploration is not a right. It is a privilege. And privilege always comes with sacrifice. The astronauts who go to Mars will not be heroes. They will be martyrs. And we will write their names in gold. And forget them by the next launch.

There is no ethical solution. Only the illusion of one. We are not preparing for Mars. We are preparing for the myth of Mars. The myth that we can go, and come back unchanged.

I love how we're all acting like this is new. We’ve been doing this since the 60s. Apollo 11? No radiation shields. No genetic screening. No ethics panels. Just men in tin cans with pencils and prayer. And they came back. And they lived. And they raised kids. And they told stories.

Now? We’ve turned space into a liability spreadsheet. We’ve replaced courage with compliance. We’ve replaced grit with GDPR.

Maybe the real problem isn’t radiation. It’s that we’ve lost the courage to risk anything anymore.

I'm from Canada and I just want to say: we’re not just talking about astronauts. We’re talking about what kind of society we are. Do we value human life enough to build better shields? Or do we value the headline more? I hope we choose life.