When we talk about finding life beyond Earth, we often focus on whether a planet is in the right orbit, has water, or a breathable atmosphere. But there’s something quieter, less talked about, that might be just as important: planetary albedo. It’s not a word you hear every day, but it’s the key to understanding whether a distant world is hot, cold, or just right for life.

Albedo is simply the measure of how much sunlight a planet reflects. A planet with high albedo-like one covered in ice or thick clouds-bounces most of the sun’s energy back into space. A low-albedo world, say, with dark oceans or dense forests, absorbs that energy and heats up. On Earth, our average albedo is about 0.31, meaning we reflect roughly one-third of the sunlight that hits us. But what if we took that same Earth-like planet and moved it around a red dwarf star? Or spun it twice as slow? Or covered it in oceans instead of land? The albedo changes. And so does everything else.

Why Albedo Isn’t Just a Number

Early models of exoplanets treated albedo like a single, fixed value. If a planet was Earth-like, scientists assumed its albedo was 0.31, no matter the star it orbited. But that’s like assuming all cars get the same gas mileage, whether they’re driving in the desert or the Arctic. It doesn’t work.

Recent breakthroughs show that surface reflectivity changes dramatically depending on the wavelength of light hitting it. Our oceans, for example, absorb near-infrared light-light that’s more common around cooler, redder stars like M-dwarfs. That means a planet orbiting such a star might absorb more heat than models predicted, simply because its surface isn’t reflecting that part of the spectrum. In fact, using wavelength-dependent albedo instead of a flat number can change a planet’s surface temperature by up to 35 Kelvin-that’s hotter than a desert on a summer day.

On the flip side, planets around hotter, bluer stars like F-type stars might end up cooler than expected because their surfaces reflect more of that blue light. This isn’t a minor tweak. It flips the script on what we thought were habitable zones. A planet once considered too cold might now be warm enough for liquid water. Another thought to be perfectly temperate might be scorching.

The Clouds That Hide the Surface

Here’s the twist: clouds don’t just reflect light-they hide what’s underneath. On Earth, clouds account for about two-thirds of our total albedo. The surface? Only one-third. And it’s not even close to evenly distributed. The Northern Hemisphere has more land, which reflects more sunlight. The Southern Hemisphere has more clouds, which do the same job. The result? A near-perfect balance. That balance is fragile. Change the cloud cover, and you change the planet’s temperature.

For exoplanets, this gets even trickier. A tidally locked planet-one side always facing its star-might have thick, bright clouds piled up on the dayside. That could make it look like a high-albedo world from space. But underneath? A scorching, dry surface. Or, if the clouds are thin or patchy, the dark surface could absorb heat, making the planet hotter than it seems. Scientists using models like the one for HD189733b have shown that even small changes in cloud location can shift the shape of the planet’s phase curve-the way its brightness changes as it orbits. That means what we see through telescopes might be lying to us.

Land, Ice, and the Hidden Role of Vegetation

Landmasses matter. A planet with 70% land and 30% ocean will reflect more light than one with the reverse. But here’s something surprising: vegetation lowers albedo. Green plants absorb light for photosynthesis, which means they reflect less than bare soil or rock. That sounds bad-less reflection, more heat-but it might actually help life survive.

Studies suggest that biological activity, like widespread plant cover, can push the outer edge of the habitable zone farther out. A planet that would otherwise be too cold to support liquid water might warm up just enough because its surface is darker. That’s not just a curiosity-it changes how we search for life. We might need to look beyond Earth-like planets and consider worlds that look *different* but are warmed by hidden biology.

And then there’s ice. Snow and ice reflect sunlight like mirrors. But as a planet cools, more ice forms, which reflects even more light, which cools it further. That’s a runaway feedback loop. On Earth, we’ve seen it happen in ice ages. On exoplanets orbiting dim stars, this could mean a planet freezes solid before life even has a chance. But if that same planet has enough greenhouse gases-or vegetation-it might avoid that fate.

Models That Think Like Real Planets

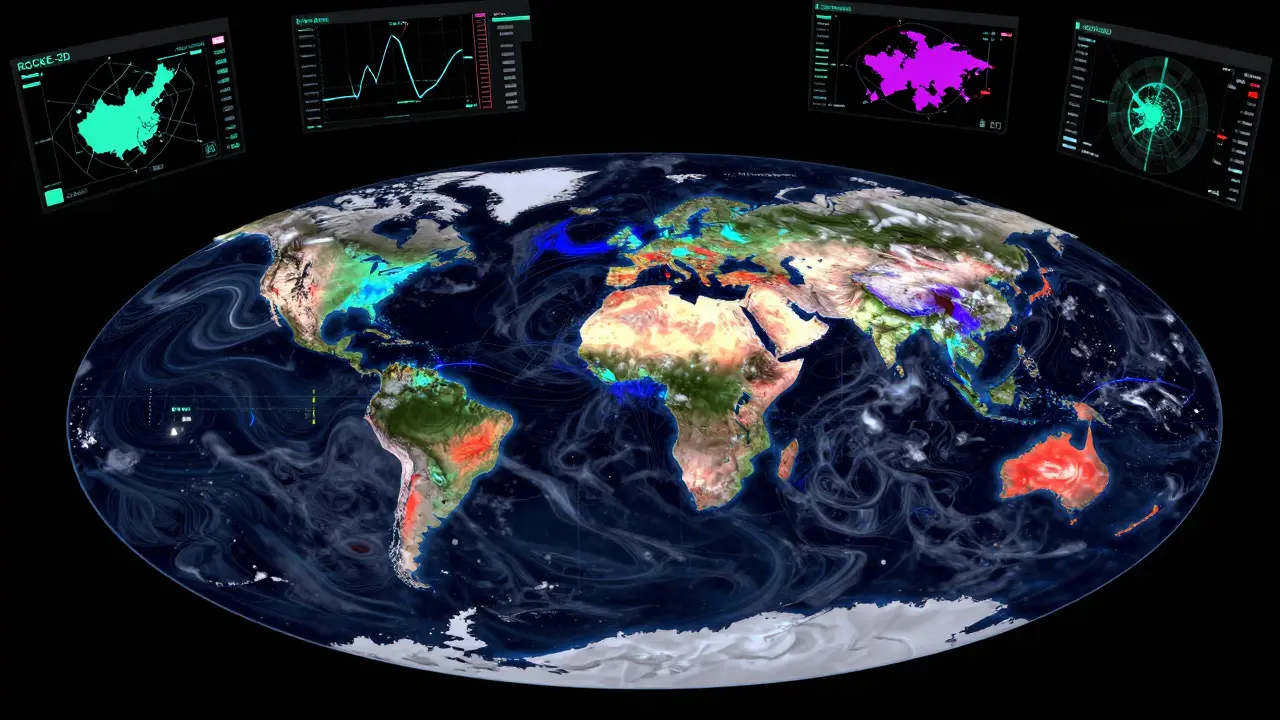

Old climate models treated planets like simple light bulbs. New ones? They’re like digital twins. The ROCKE-3D model, for example, simulates planets with rotation periods from one day to 128 days, and axial tilts from zero to 90 degrees. Scientists ran 70 simulations just to see how albedo shifts under different conditions. They found that changing a planet’s spin or tilt doesn’t just affect wind patterns-it rewrites how much heat is trapped, how clouds form, and how much sunlight gets reflected.

Another model, exo-Prime, was updated to include wavelength-dependent albedo for both clouds and surfaces. The result? A planet with 44% cloud cover and realistic surface reflectivity produced the same temperature as a model using a flat albedo of 0.31. That means we can’t assume a planet’s albedo is fixed-it’s a product of its atmosphere, surface, and star.

And then there’s the EOS-ESTM model, built specifically for rocky, temperate worlds. It doesn’t just calculate temperature. It simulates how heat moves through the atmosphere, how winds circulate, how oceans might distribute warmth. It’s not just predicting climate-it’s building a living world on a computer.

What We Can Predict-And What We Can’t

Here’s the good news: we don’t need to know everything about a planet to guess its albedo. Researchers have found that with just two things-the amount of starlight hitting the planet and the star’s temperature-we can predict Bond albedo (the total reflectivity across all wavelengths) with surprising accuracy. For planets around Sun-like stars, Earth’s albedo is near the minimum possible. Too much light? Clouds rise and reflect more. Too little? Ice forms and reflects even more. There’s a natural balance.

But for planets around M-dwarfs? The story changes. Water vapor absorbs infrared light, so even with ice, the albedo stays low. That means these planets are more likely to be hot. Unless, of course, they have thick clouds. That’s why we can’t rely on one-size-fits-all rules.

Statistical tools like the Alternating Conditional Expectations (ACE) algorithm are now helping scientists find hidden patterns. They’ve found that increasing a planet’s day length or land fraction lowers surface temperature. Greenhouse gases? They raise it. But the relationships aren’t simple. They’re nonlinear, tangled, and messy. That’s why we need models that don’t just plug in numbers-they explore how everything interacts.

The Bigger Picture: Albedo as a Climate Regulator

On Earth, we’re seeing albedo change in real time. Melting ice, deforestation, urban sprawl-all of it reduces our planet’s reflectivity. That’s a major driver of global warming. What we’re learning about exoplanets is helping us understand our own planet better. And what we learn about Earth is helping us interpret alien worlds.

Planetary albedo isn’t just a number. It’s a fingerprint. It tells us about clouds, oceans, ice, forests, and maybe even life. A high albedo doesn’t mean a planet is dead. It might mean it’s covered in clouds that keep it cool. A low albedo doesn’t mean it’s a desert. It might be a world teeming with life, absorbing sunlight like a forest.

As we look toward next-generation telescopes like the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope or future missions with advanced spectrographs, we’ll start seeing not just dots of light-but spectra. And from those spectra, we’ll begin to reconstruct the climate, the weather, the surface, and maybe even the biosphere of distant worlds.

The search for life beyond Earth isn’t just about finding water or oxygen. It’s about understanding how light dances across a planet’s surface and atmosphere. And that dance? It starts with albedo.

What is planetary albedo and why does it matter for exoplanets?

Planetary albedo is the fraction of incoming starlight that a planet reflects back into space. It matters because it directly controls how much energy the planet absorbs, which determines surface temperature and whether liquid water can exist. For exoplanets, where we can’t land probes or take direct measurements, albedo is one of the few clues we have about climate and potential habitability.

How do scientists measure albedo for planets they can’t see up close?

Scientists use phase curves-measurements of how a planet’s brightness changes as it orbits its star. By analyzing how light reflects at different angles and wavelengths, they can infer cloud cover, surface type, and overall reflectivity. Combining this with climate models and known star properties allows them to estimate albedo without ever seeing the planet’s surface.

Why is wavelength-dependent albedo better than a single average value?

Different surfaces reflect light differently across wavelengths. Oceans absorb near-infrared light, while ice reflects it. A flat albedo value (like 0.31) ignores this, leading to big errors. Wavelength-dependent albedo accounts for how a planet’s surface interacts with its specific star’s light, making temperature predictions accurate enough to tell if a world is truly habitable.

Can vegetation on an exoplanet affect its albedo and climate?

Yes. Vegetation lowers planetary albedo because plants absorb visible light for photosynthesis instead of reflecting it. This warming effect can push the outer edge of the habitable zone farther from the star, meaning life might survive on planets previously thought too cold. This suggests biological activity could expand the range of places where life is possible.

Do all exoplanets around M-dwarf stars have low albedo?

Not always. While M-dwarf planets often have low albedo due to water vapor absorbing infrared light, high insolation can trigger thick cloud formation, which increases reflectivity. The balance between surface absorption and cloud reflection determines the final albedo. Some M-dwarf planets may even have higher albedo than Earth, depending on cloud coverage.

How do climate models like ROCKE-3D help predict albedo?

ROCKE-3D simulates how rotation, axial tilt, and starlight distribution affect cloud formation, surface temperature, and atmospheric circulation. By running hundreds of simulations with different planetary parameters, scientists can see how albedo shifts under realistic conditions. This helps identify which types of exoplanets are most likely to have stable, Earth-like climates.

Is albedo the only factor in determining if an exoplanet is habitable?

No. Albedo is one piece of a larger puzzle. Atmospheric composition, greenhouse gases, orbital eccentricity, tidal locking, and geological activity all play roles. But albedo is critical because it determines the planet’s energy budget-the balance between incoming and outgoing heat. Without accurate albedo, even the best models of atmosphere or water content can be wrong.

11 Responses

It’s wild how something as simple as how much light a planet reflects can decide whether life has a chance or not. I’ve always thought of habitable zones as just distance from the star, but albedo? That’s the quiet puppet master behind the scenes. It makes me wonder - if we ever find a planet with a weirdly low albedo, maybe it’s not a desert. Maybe it’s covered in alien forests, soaking up light like a leaf on a summer day. We’re not just looking for Earth 2.0. We’re looking for life in all its strange, reflective forms.

albedo is like the planets skin tone lol imagine if earth had no clouds and just dark oceans we’d all be boiling and no one even talks about it like its normal but its the most important thing ever

They say albedo changes everything but let’s be real - this is all just climate science dressed up to look fancy. They’re trying to scare us into believing Earth is fragile. What they don’t say is that the sun’s output changes way more than any planet’s reflectivity. And don’t get me started on how they ignore solar cycles. This whole exoplanet albedo thing? Just another way to push the same old agenda - control the narrative, control the planet.

so like… albedo is just how shiny a planet is right? i mean i get the whole ice reflects light and forests absorb thing but why are we making it sound like a super complex physics thing? its basically like wearing a white shirt vs black shirt in summer. why do we need 70 simulations and fancy models? i think we’re overcomplicating it. also i think i misspelled something in this comment. who cares.

This is one of those topics that makes me feel hopeful. We’re not just guessing anymore. We’re building models that think like planets - rotating, cloud-covered, forested, icy worlds. It’s like we’re learning to see the universe not as a collection of dots, but as living systems with rhythms and balances. The fact that vegetation might push the habitable zone outward? That’s beautiful. It means life isn’t just surviving - it might be shaping the world around it. We’re not alone in the universe. We’re part of a pattern.

It is important to understand that albedo is a natural part of planetary systems. The balance between reflection and absorption is delicate. We must not assume that any single factor determines habitability. Each planet is unique. The models we build should reflect this complexity with care and humility. Science is not about certainty. It is about understanding the unknown with patience.

I’m curious - if a planet has high albedo because of thick clouds but the surface is actually hot and dry underneath, how do we tell the difference from Earth? Is there a way to detect surface conditions just from the phase curve? Or are we still stuck guessing based on assumptions? I feel like we’re missing a piece of the puzzle here.

You know what’s amazing? We’re finally starting to see planets as whole systems - not just rocks with atmospheres. Albedo isn’t just physics. It’s chemistry. It’s biology. It’s weather. It’s history. When we find a world with low albedo around a red dwarf, don’t just call it hot. Ask: is there life down there, dark and deep, pulling light into its roots? Maybe we’re not looking for life in the right way. Maybe it’s hiding in the shadows - and we’re the ones who need to learn how to see it.

Interesting how the models show that even small changes in rotation or landmass can flip the albedo game. I didn’t realize that increasing day length could cool a planet. That’s counterintuitive. Also, the part about vegetation lowering albedo but actually helping warmth? That’s poetic. Life doesn’t just adapt - it engineers its environment. We should be thinking about biosignatures not just as gases in the air, but as surface patterns. Maybe future telescopes will see the ‘glow’ of alien forests.

There is a profound elegance in the way planetary albedo emerges from the interaction of surface, atmosphere, and stellar radiation. It is not a static parameter but a dynamic equilibrium shaped by countless variables. The shift from fixed albedo values to wavelength-dependent models represents not merely an improvement in computation, but a deeper philosophical recognition: that nature resists simplification. We must honor that complexity.

So albedo is what keeps planets from getting too hot or too cold. That’s all I needed to know. Thank you for explaining it clearly.