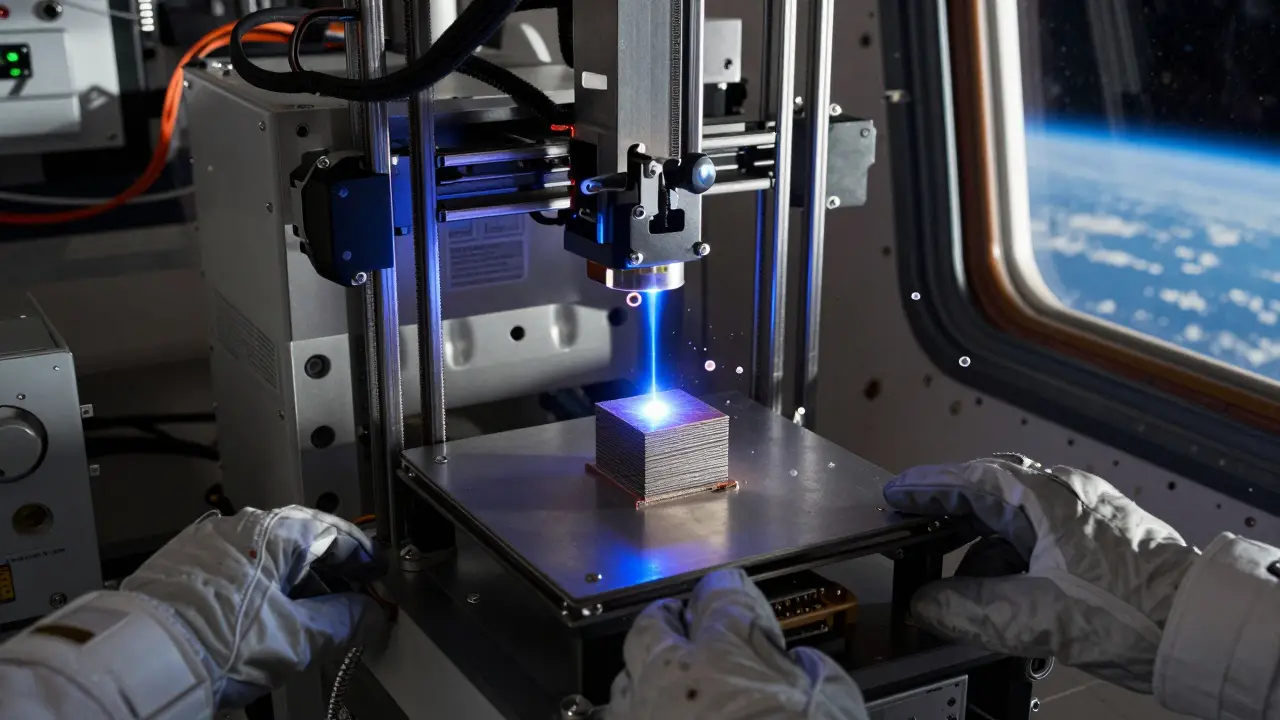

For decades, astronauts relied on Earth to send every screw, tool, and spare part. But what if they could make those things themselves - right in space? That’s no longer science fiction. In August 2024, NASA and the European Space Agency pulled off something never done before: they printed a metal part in zero gravity aboard the International Space Station. Not plastic. Not resin. Real, strong, stainless steel - melted by a laser at 1,200°C and shaped layer by layer without gravity to help or hinder.

How It Actually Works in Zero-G

The machine doing this isn’t some futuristic lab gadget. It’s a compact, 45-kilogram box, about the size of a small microwave, called the ESA Metal 3D Printer. It doesn’t use powder like Earth-based metal printers. Instead, it feeds thin stainless steel wire into a sealed chamber, where a high-powered laser melts it drop by drop. The whole process happens inside a nitrogen-filled bubble to keep oxygen out - because in space, oxygen near a hot laser is a fire risk. The printer’s build volume? Just 10x10x10 cm. Small, yes. But that’s enough to make wrenches, brackets, or even spacecraft nozzles. Each print takes 2 to 8 hours. Crew members don’t watch it the whole time. They set it up, hit start, and let it run. But the setup? That’s where things get tricky. Loading the wire in zero-G? Takes 45 minutes. Replacing the station’s air with nitrogen? Another 30. Retrieving the finished part? 20 minutes. Total crew time per job: about 2 hours. And that’s after 16 hours of training.Why This Matters More Than You Think

Imagine you’re on a six-month trip to Mars. Your ship breaks down. A critical valve fails. You can’t call Amazon for a replacement. Even if you could, it would take months to get there. That’s the reality of deep space. Every kilogram you launch from Earth costs about $2,700. Sending a spare part for a broken pump? That’s $50,000 - and you’re still waiting months. Metal 3D printing changes that. Instead of launching hundreds of spare parts you might never need, you launch a printer and a spool of wire. You print what you need, when you need it. NASA estimates this could cut launch mass by up to 30% on long missions. That means more science gear, more food, more fuel - or smaller, cheaper rockets. It’s not just about tools. Think medical. A broken dental tool on the ISS? Print a new one. A custom splint for an injured astronaut? Print it. The potential isn’t just logistical - it’s life-saving.What’s Different About Printing in Space?

On Earth, gravity helps. Molten metal sinks. Gases rise. That’s how you get even layers and clean structures. In space? Nothing sinks. Nothing rises. The molten metal just floats. And that’s where things get weird. Early tests showed the process was surprisingly stable. NASA found that microgravity didn’t break the printing - it changed it. Without gravity pulling the melt down, the material forms more uniformly. Less porosity. Fewer air bubbles. Some scientists think the parts might even be stronger. But there’s a catch: without gravity to guide flow, the metal can behave unpredictably. One print might turn out perfect. The next? Slightly warped. Early samples showed dimensional errors up to 0.2mm - enough to make a nozzle leak or a bolt not fit. Engineers fixed most of that with software updates. The SpaceX-33 mission in September 2025 brought new firmware that improved material flow control. Now, success rates are near 100%. But the real test is still ahead: comparing space-printed parts to Earth-made ones. Are they truly better? Or just different?

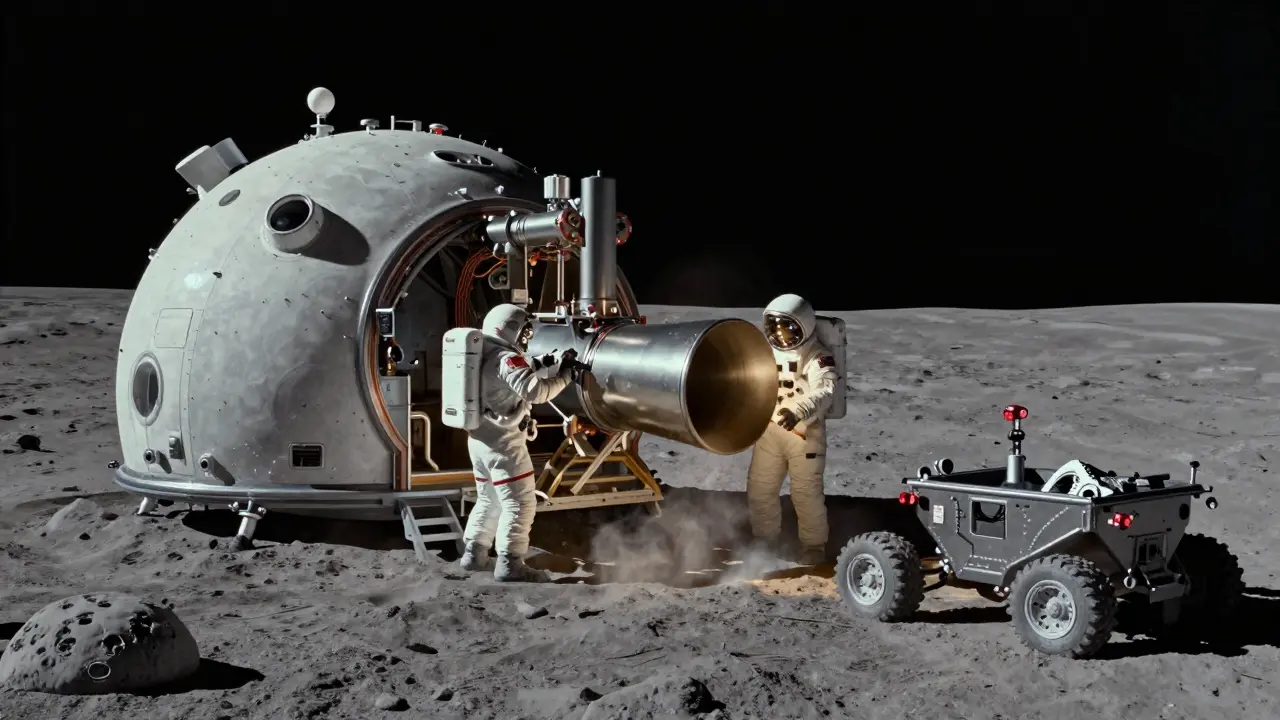

What’s Been Printed So Far?

The first four prints were simple: cubes, cylinders, and geometric shapes. Nothing fancy. Just proof-of-concept. But the next batch? That’s where it gets real. In late 2025, astronauts started printing actual spacecraft components - two tiny rocket nozzles. Not models. Functional ones. Designed to mimic parts used in propulsion systems. If these hold up under pressure tests back on Earth, they could be used in future missions. They’ve also printed multiple versions of the same part using different laser speeds and wire feed rates. Why? To find the sweet spot - the exact settings that work best in zero-G. It’s like cooking. You don’t just follow the recipe. You tweak it until it tastes right.Who’s Working on This - And Who’s Behind?

This isn’t just NASA. It’s a global team. The printer was built by Airbus Defence and Space in Europe, under contract with ESA. NASA provided the space station, the crew, and the mission control. The materials? Stainless steel 316L and titanium alloys, shipped up on SpaceX cargo flights. Future upgrades will add aluminum and copper - materials critical for electronics and heat shields. Private companies are racing to catch up. Made In Space (now part of Redwire) has been printing plastic parts on the ISS since 2014. Vast Space is building its own in-orbit factory. But metal? Only ESA and NASA have cracked it so far. The numbers tell the story. In 2025, 100% of ISS missions used 3D printing - but only for plastic. Only 32% used metal. That’s about to change. By 2028, analysts predict metal printing will be routine on the ISS. By 2032, it’ll be standard on lunar missions.

15 Responses

This is all fine and dandy, but let's be real - we're just replacing one expensive habit with another. Why not just launch pre-made parts? This printer uses more power than a small apartment. And who's paying for the nitrogen bubbles? Someone's got to cover the electricity bill in orbit.

I love how this is turning space into a place where you can just fix stuff instead of waiting for help. I remember when my bike chain snapped on a trail - if I had a mini 3D printer, I’d’ve printed a new link right there. Same idea, just way cooler and farther from Earth.

"Metal 3D printing in zero gravity" - technically inaccurate. It's not zero gravity, it's microgravity. And "stainless steel" isn't a material, it's an alloy family. Also, "drop by drop"? That's not how wire-fed L-PBF works. You're melting a continuous feed. Fix your language before you write science.

This is the future and it's already here. Imagine being able to make your own tools on Mars. No more waiting. No more begging Earth for help. We're not just visiting anymore. We're building. And that changes everything. The real revolution isn't the printer - it's the mindset.

It is imperative to note that the article exhibits a distressing lack of technical precision. The term "zero gravity" is scientifically erroneous and perpetuates public misunderstanding. Furthermore, the casual tone undermines the gravity of space-based manufacturing. This is not a DIY project; it is a pinnacle of aerospace engineering. Please exercise greater rigor in future communications.

Wait… why is this only happening now? Who funded this? And why is no one talking about the fact that this tech was reverse-engineered from classified DARPA projects in the 2010s? I’ve seen the leaked docs. This isn’t innovation - it’s a cover-up. They’ve been doing this for a decade. The "first ever" claim is a lie to make it look like NASA did it.

While the article presents a compelling narrative regarding the technological advancements in additive manufacturing within microgravity environments, it is, regrettably, marred by a series of grammatical and syntactical infelicities. For instance, the phrase "drop by drop" is not only imprecise but also misleading in the context of wire-fed laser powder bed fusion systems, which operate on a continuous feedstock mechanism. Furthermore, the assertion that "nothing sinks, nothing rises" is an oversimplification that ignores the role of surface tension, Marangoni convection, and capillary forces - phenomena which remain active and influential in the absence of gravitational acceleration. One must be vigilant against the propagation of scientifically inaccurate metaphors, even when they are rhetorically convenient.

It’s wild to think that a microwave-sized box in orbit can make a wrench. I’ve watched videos of astronauts loading that wire - looks like they’re threading a needle while floating. I wonder how many times they’ve dropped it. Probably a lot. But they keep trying. That’s the real story - not the tech, but the patience.

Let’s not pretend this is some miracle. They spent $200 million to print a cube. And now they want to send this to Mars? What happens when the laser overheats and melts the whole station? Or when a printed bolt fails mid-mission and kills someone? This isn’t innovation - it’s a vanity project disguised as necessity. We’re throwing money at shiny toys while ignoring basic life support upgrades. The real problem isn’t broken parts - it’s the mindset that says "build it in space" instead of "don’t break it in the first place." And don’t even get me started on the "life-saving" claims. You think a printed dental tool is going to save someone on Mars? The real medical crisis is radiation exposure and muscle atrophy - not a chipped tooth.

Is this progress? Or just another way for humanity to avoid confronting its own fragility? We build machines to replace our dependence on Earth - but what are we really escaping? The truth is, we are still children playing with tools we don’t understand, pretending we’ve outgrown the need for home. The printer hums. The metal cools. And still, we are alone - more than ever.

Okay, so let me get this straight - we’re printing metal in space, using wire, not powder, and it’s actually working? That’s insane. And the fact that they’ve got success rates at 100% now? That’s not luck - that’s engineering. And the fact that they’re testing real rocket nozzles? That’s not a demo - that’s the future. I mean, think about it - no more waiting for Earth. You break something? Print it. No more waiting. No more begging. Just… make it. This is the moment we stop being explorers and become builders. And honestly? That’s the most powerful thing I’ve heard in years.

It’s quiet, isn’t it? That’s what I think about - the silence in space, the hum of the laser, the slow drip of molten steel forming something useful. No crowds. No noise. Just a machine making a tool, in the dark, far from home. That’s beautiful.

So… we spent billions to print a wrench in space so we don’t have to wait six months for one? And you call this progress? I’d rather have a spare wrench and a good book than a printer that needs a nitrogen bubble and two hours of training just to load a spool of wire. This isn’t the future - it’s a very expensive solution to a problem we could’ve solved with duct tape and common sense.

Man I just watched a video of an astronaut trying to load the wire and he dropped it like three times. Took him 10 minutes to catch it with a magnet. And they trained for 16 hours? I think I’d rather just have a box of spare bolts. But hey… if it works, it works. Still wild to think about. I mean… printing parts on Mars someday? That’s like sci-fi becoming real. I’m just glad someone’s actually doing it instead of just talking about it.

That’s actually a great point. I bet the astronauts are just glad they don’t have to wait for a resupply ship. I mean, if your pressure valve fails on Mars, you don’t get a UPS delivery. You print it. Or you don’t make it home. Simple as that.