The lunar south pole isn’t just another spot on the Moon. It’s the most important place we’re sending robots and, someday, humans-not because it’s beautiful, but because it holds something we can’t afford to ignore: water ice.

For decades, scientists guessed it might be there. The Moon’s axis barely tilts-just 1.6 degrees-so some craters at the south pole never see sunlight. They’re frozen in eternal night. Temperatures there stay below -163°C. In those dark, icy traps, anything that ever landed-comet dust, solar wind particles, even ancient asteroid debris-could have survived for billions of years. And now, we know it’s true. Water ice is real. Not just a little. Enough to change everything.

How We Found the Ice

No single mission found it. It took decades, multiple spacecraft, and clever science to piece it together.

In 1994, NASA’s Clementine probe bounced radar signals off the lunar surface. One crater showed a strange echo-like ice reflecting radio waves. It wasn’t proof, but it was a hint. Then came Lunar Prospector in 1998. Its neutron spectrometer measured hydrogen levels near the poles. The numbers were too high to be random. It pointed to water ice mixed into the top 40 centimeters of soil-about 1.5% by weight. Still, hydrogen could mean other things: hydroxyl, hydrated minerals, even solar wind protons stuck in the dirt.

The real smoking gun came in 2018. Scientists analyzed data from India’s Chandrayaan-1 orbiter, specifically from the Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3). They spotted the unmistakable fingerprint of water ice in near-infrared light-absorption peaks at 1.3, 1.5, and 2.0 micrometers. That’s the signature of H₂O molecules. The ice wasn’t a giant glacier. It was scattered-grains mixed into the regolith, like sugar in sand. Concentrations? 5 to 10% in some spots. Enough to matter.

Then came ShadowCam in 2022. Mounted on South Korea’s Lunar Pathfinder Orbiter, this camera could see in light a million times dimmer than daylight. It showed us the actual surface of the darkest craters. And what did it find? Ice, yes-but far less than expected. Only about 20% of the visible surface in permanently shadowed regions had ice. The rest? Rock, dust, and shadows. That surprised everyone. We thought we’d find icy plains. Instead, we found ice patches, like islands in a sea of rock.

What the Ice Looks Like-and Where It Hides

It’s not like Antarctic glaciers. Lunar ice doesn’t form smooth sheets. It’s buried, mixed, and trapped.

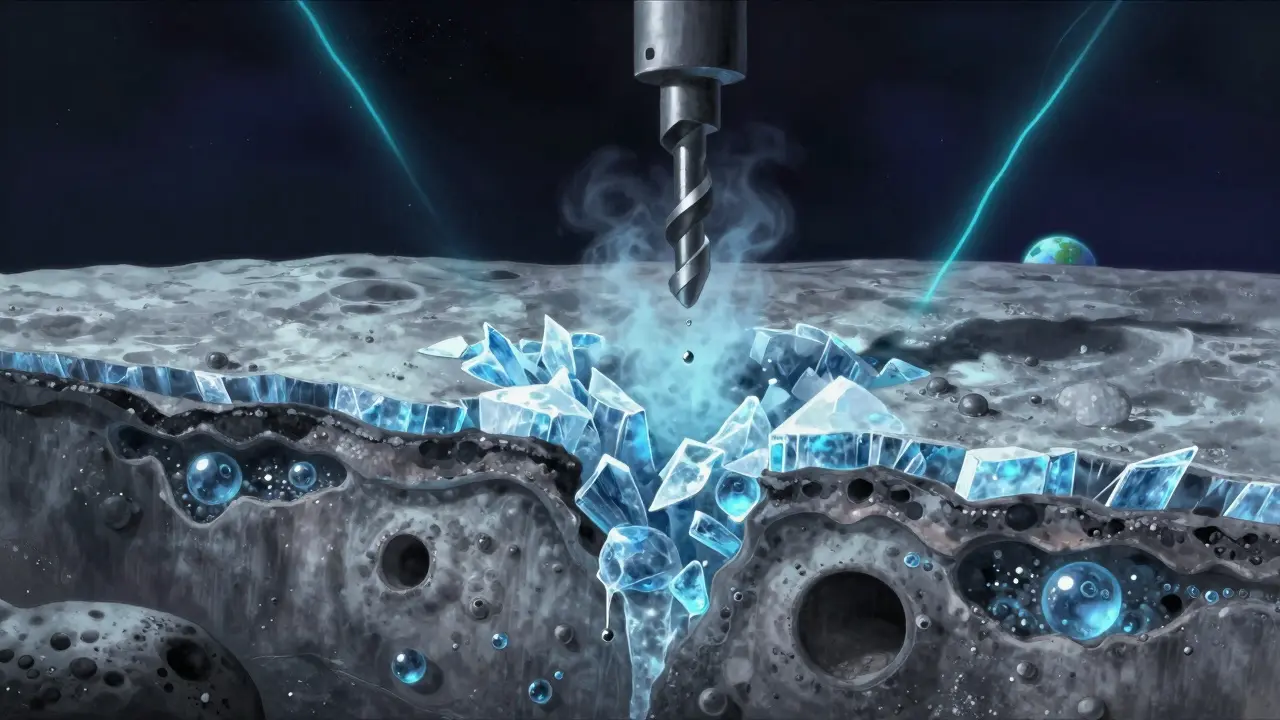

Some ice is right near the surface, within the top 40 cm, confirmed by Lunar Prospector and later by NASA’s PRIME-1 drill in 2025. That’s the easy stuff-maybe reachable with a simple scoop. But deeper? That’s where things get tricky. Computer models suggest ice might stretch down over a meter, frozen into the regolith like a frozen cake. We haven’t dug that deep yet. The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter’s Mini-RF radar shows weird radar signatures in some craters-high circular polarization ratios-that match ice. But rough terrain can fool radar too. So it’s suggestive, not certain.

There’s also ice trapped inside glassy beads formed by ancient micrometeorite impacts. And ice clinging to the inside of tiny pores between soil grains. In 2023, a study in the Journal of Geophysical Research proposed that some ice might be locked in these microscopic voids, making it harder to extract than we thought.

And then there’s the deep ice-maybe buried under meters of dust. That’s where new tech comes in. A team at the Hawaiʻi Institute of Geophysics and Planetology is testing cosmic ray radar. When high-energy cosmic rays hit the Moon, they produce neutrons that bounce back differently if they hit ice. This method could map ice down to 2 meters deep-without drilling. Field tests are planned for early 2026.

Why It Matters: Science and Survival

Water isn’t just nice to have. It’s life support, fuel, and a scientific treasure chest.

Split water into hydrogen and oxygen, and you’ve got rocket fuel. Oxygen for breathing. Hydrogen for power. If we can extract it on the Moon, we don’t need to haul it from Earth-where it costs $1 million per kilogram to launch. That changes the economics of space. NASA’s Artemis program aims to build a long-term base by 2030. Without local water, it’s impossible.

Scientifically, lunar ice is a time capsule. It’s been frozen since the early solar system. The hydrogen isotopes in the ice could tell us where it came from-comets? Asteroids? Solar wind? That tells us how water got to Earth, too. And if there’s organic material trapped with it? That could rewrite our understanding of how life’s building blocks spread through the solar system.

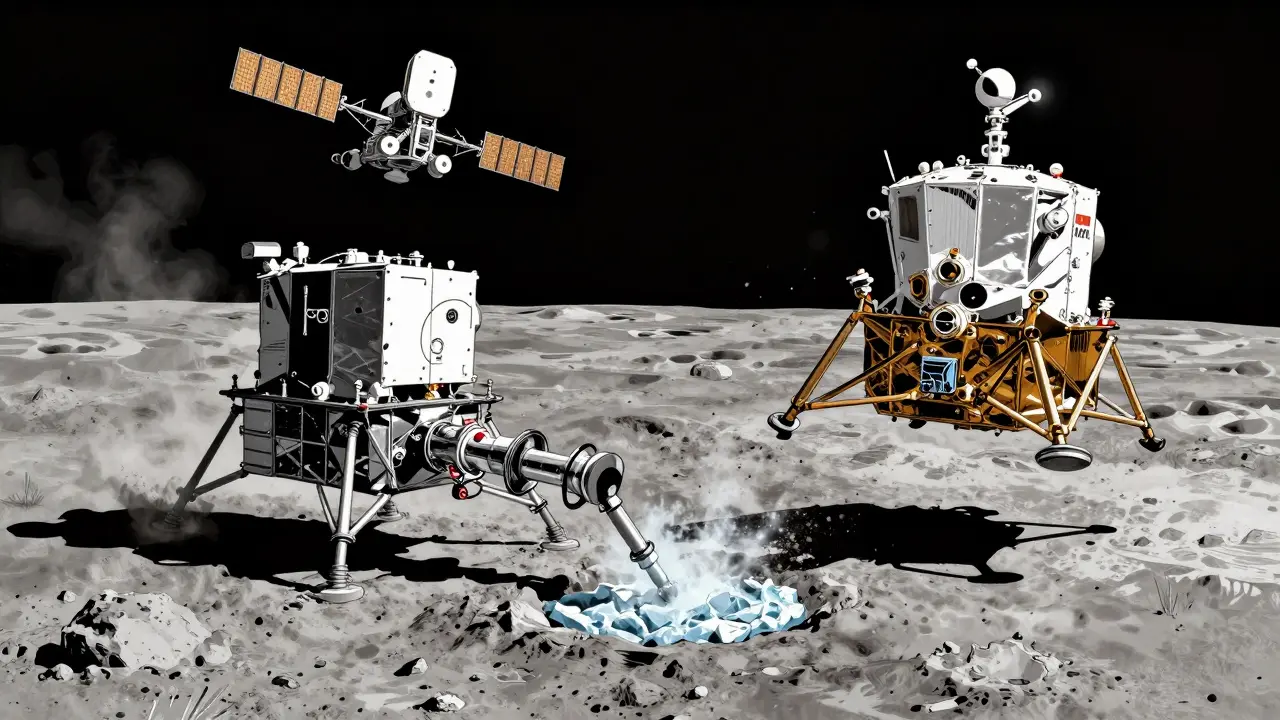

China’s Chang’e-7 mission, launching in late 2026, will send a mini-flying probe into shadowed craters with a Lunar Water Molecular Analyzer. It’s designed to hop between ice patches, sampling and analyzing right where it lands. India’s Chandrayaan-4 (2028) and Russia’s Luna-27 (2025) are also targeting the south pole with ice-detecting tools. Every major space agency is now focused here.

The Challenges: Cold, Dark, and Hard

Getting to the ice is harder than finding it.

Temperature is the enemy. Electronics fail below -50°C. Instruments designed for room temperature freeze solid. NASA’s Ice-Mining Experiment-1, launched in February 2025, had to build custom cryogenic systems. During a test at NASA’s Glenn Research Center, the drill survived only 45 minutes in simulated lunar cold.

Navigation in total darkness? Impossible with cameras. ShadowCam solved this by using star patterns to orient itself-like a cosmic GPS. But that’s only for orbiters. Landers need new tricks. China’s mini-probe uses a hopping system, tested in Antarctica’s dry valleys during summer 2024. It’s like a lunar kangaroo, bouncing from one icy patch to another.

Drilling in frozen regolith? It takes three times more power than on Earth. The University of New Mexico tested drills in lunar analog soils at -150°C. The motors burned out fast. New materials, new designs, new power systems-all needed.

And the ice itself? It’s not pure. It’s mixed with dust, rock, and glass. Extracting clean water means heating the soil to over 100°C, then capturing the vapor. That’s energy-intensive. And we still don’t know how much we can actually get out. Estimates vary wildly: 100 million to 600 million metric tons. That’s enough for decades of lunar operations-if we can reach it.

Who’s Going There-and When

The race is on. And everyone’s bringing ice-hunting gear.

- NASA: Artemis III (2026) will land near the south pole. PRIME-1 (2025) already drilled 1 meter into the regolith and analyzed samples. Future CLPS landers will carry ice-detection tools.

- China: Chang’e-7 (2026) will deploy a flying probe with the LWMA. Chang’e-8 (2028) will test ISRU (in-situ resource utilization) tech-like turning ice into oxygen.

- India: Chandrayaan-4 (2028) will carry a mass spectrometer to analyze ice composition.

- Russia: Luna-27 (2025) carries the PROSPECT drill and lab, designed to extract and analyze ice in real time.

- Japan, ESA, UAE: All have missions planned for the south pole by 2030.

Every mission since 2020 includes ice detection. That’s 100% of lunar south pole missions. No one’s going there just to plant a flag anymore. They’re going to dig.

The Big Unknowns

Here’s where the science gets messy.

Paul Lucey at the University of Hawaii says some of the hydrogen we detect might not be ice at all. It could be hydrogen atoms from the solar wind, stuck in the soil. That’s a big deal-if true, we might not have as much water as we think.

And what about the ice we can’t see? ShadowCam shows surface ice is sparse. But cosmic ray radar might reveal deep, dense layers we’ve never touched. Are we missing half the ice? Maybe.

Legal questions hang over it too. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty says no country can own the Moon. But the 2020 Artemis Accords-signed by 38 nations-say you can use what you find. Who gets the water? Who controls the mines? There are no rules yet. Just promises.

And then there’s the cost. Building a mining operation on the Moon is harder than landing on Mars. We’ve never done it. The first real test-extracting and using lunar ice-is still ahead of us. NASA’s Ice-Mining Experiment-1 will deliver its first results in April 2025. That’s the moment we’ll find out if it’s even possible.

What’s Next?

By 2030, we’ll have detailed 3D maps of ice concentration across the south pole-depth, purity, location. Shuai Li’s team at the University of Hawaii is already building them. That’s the key. You don’t just want to know ice is there. You want to know where to dig.

Once we have those maps, the next step is mining prototypes. Not just drills. Systems that can survive years in the dark, extract water, store it, and turn it into fuel-all automatically. That’s the real challenge. Not finding ice. Using it.

The lunar south pole isn’t just a scientific curiosity. It’s the first step toward a future where humans live beyond Earth. The ice is the reason we’re going. The question isn’t whether we can find it. It’s whether we’re ready to use it.