Getting around on the Moon isn’t like driving on Earth. The gravity is just one-sixth, temperatures swing from -173°C to 127°C, and a fine, abrasive dust clings to everything. No roads. No GPS. No cell service. So how do astronauts move around? The answer lies in three very different kinds of lunar mobility systems: hoppers, unpressurized rovers, and pressurized vehicles. Each solves a different problem - and together, they’ll shape the future of human presence on the Moon.

Unpressurized Rovers: The Workhorses of the Lunar Surface

The most common type of lunar vehicle right now is the unpressurized rover - basically a rugged, remote-controlled golf cart built for space. These aren’t meant to carry people inside. Astronauts wear full space suits and ride on top or walk alongside. Think of them as mobile toolboxes.

Intuitive Machines’ Moon RACER is leading this category. It’s designed to travel up to 20 kilometers from a landing site, carry 500 kg of equipment, and last for 10 years. It has eight wheels, each with its own motor, letting it climb over 50 cm rocks and turn on a dime. Power comes from regenerative fuel cells - the kind that recycle energy from braking - giving it 200-300 kWh of storage. That’s enough to run for days without sunlight.

What makes Moon RACER special isn’t just its parts. It’s how smart it is. Inside, it runs autonomy software trained on over 50,000 simulated lunar images. During testing at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, it navigated rocky terrain using LiDAR and cameras, even in low-light conditions. In 2025, it completed a 5 km test in Arizona’s desert, matching real lunar terrain from LRO imagery. The system hit 95% path accuracy - far better than Apollo-era navigation.

These rovers are cheaper, too. Development costs hover around $200-300 million, compared to billions for pressurized versions. NASA plans to award its first major contract for these vehicles by late 2025, with delivery expected by 2028. They’ll haul science gear, collect samples, and even help set up habitats. But they have one big flaw: astronauts are always exposed to radiation and extreme cold.

Pressurized Vehicles: Living Rooms on Wheels

What if you could drive for days without ever putting on a spacesuit? That’s the promise of pressurized lunar vehicles - essentially mobile habitats on wheels.

These aren’t just bigger rovers. They’re fully sealed, climate-controlled cabins with sleeping bunks, life support, and lab space. They can carry up to four astronauts for multi-day trips covering 500-1,000 km. That means you could travel from the lunar south pole to the edge of Shackleton Crater, studying ice deposits along the way.

But they come with trade-offs. A pressurized vehicle weighs 5,000-10,000 kg - more than five times heavier than an unpressurized rover. That means you need a much larger lander to deliver it. Intuitive Machines’ Nova-D lander, designed to carry these vehicles, can lift 1,000 kg to the surface. Smaller landers? Not enough.

Development costs? $1.5-2 billion. That’s why NASA is moving slowly. The Lunar Terrain Vehicle (LTV) program is still in design, with testing expected to ramp up after 2027. One major challenge? Power. A pressurized cabin needs constant heating, air recycling, and life support. That’s 5-10 kW of continuous power - twice what a rover needs. Solar panels won’t cut it during the 14-day lunar night. Nuclear or advanced batteries are being explored.

And then there’s dust. Lunar regolith sticks to everything. In Apollo, it clogged joints and degraded solar panels. Modern designs use electrodynamic dust shields - thin electric fields that push dust away. NASA tested these in 2024 and saw 80% less adhesion. Still, it’s not perfect. A 2025 report from the Aerospace Corporation warned that dust can reduce LiDAR performance by 30-40%, making navigation harder.

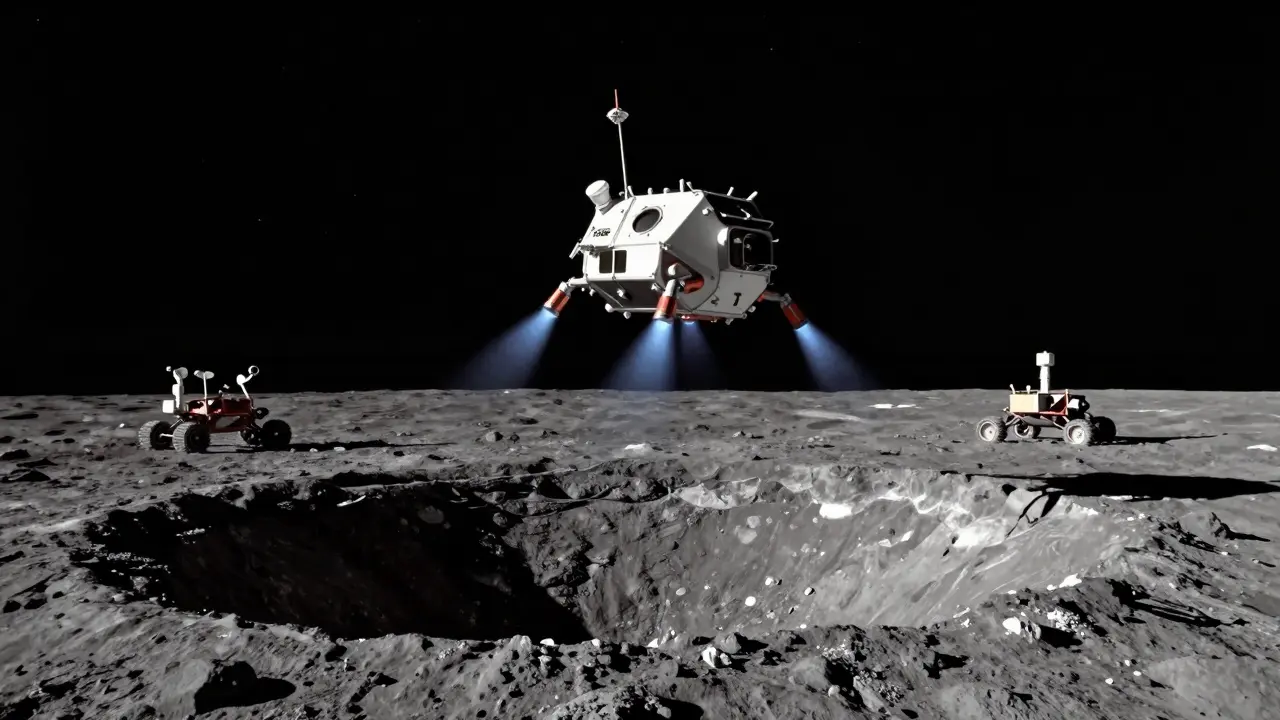

Hoppers: The Wild Card of Lunar Mobility

Then there’s the idea that sounds like science fiction: hopping across the Moon.

Hoppers use small rocket engines to leap over obstacles - craters, cliffs, permanently shadowed regions where rovers can’t go. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory has tested small prototypes that can jump 50-100 meters at speeds of 5-10 m/s. The idea? Land, hop to the next target, land again. No wheels. No tracks. Just pure vertical motion.

Why bother? Because some of the Moon’s most valuable spots - like ice in craters that never see sunlight - are unreachable by wheeled vehicles. Hoppers could drop sensors into these dark zones, then leap back to a rover base to relay data.

But here’s the catch: they’re still experimental. No hopper has flown on the Moon. They need precise fuel control, extreme thermal tolerance, and autonomous landing systems. A single miscalculation could send a hopper tumbling into a crater. Experts like Dr. Philip Metzger argue that hoppers might be the only way to explore permanently shadowed regions. But they’re not ready for prime time. Don’t expect to see one before 2030.

Autonomy: The Real Game-Changer

None of these vehicles can be driven like a car. The Moon is too far. Radio signals take 2.5-3 seconds to travel one way. That means if you hit the brakes on Earth, the vehicle only reacts three seconds later - by then, it’s already crashed.

So everything has to be autonomous. Moon RACER uses AI trained on lunar terrain maps. It identifies rocks, slopes, and shadows in real time. In NASA’s 2024-25 Lunar Autonomy Challenge, university teams competed to see who could make a rover navigate 10 km of simulated lunar surface. The best hit 89.7% success rate - but only in simulation.

Real-world testing showed bigger problems. MIT’s entry used 85% of its energy just to cover 5 km. Another team’s sensors failed when dust coated the lenses. And radiation? It’s the silent killer. Commercial systems average 3-5 single-event upsets per 100 hours - meaning computers randomly reboot or glitch.

That’s why NASA demands 99.9% operational availability. One failure could strand astronauts. That’s why Intuitive Machines built a six-degrees-of-freedom simulator that mimics lunar gravity and terrain. Astronauts train for 40-60 hours before ever stepping onto a real vehicle. The goal? Make the system so intuitive, it feels like driving a truck on Earth.

Challenges No One Talks About

Most articles focus on the cool tech. But the real problems are quieter.

- Dust: It’s not just dirty. It’s electrically charged, sharp, and gets into every seal. Apollo missions lost wheel motors after 50-100 km. Modern designs use electrodynamic shields and sealed bearings, but long-term reliability is still unproven.

- Thermal swings: A vehicle that runs hot at noon freezes solid at night. Phase-change materials absorb heat during the day and release it at night - but they add weight and complexity.

- Communication dropouts: During lunar night, Earth-based signals fade. Some vehicles now use relay satellites around the Moon or link directly to the Lunar Gateway. Still, 12% of operations lose signal for minutes at a time.

- Power management: Solar panels don’t work for 14 days. Batteries degrade. Fuel cells need hydrogen - and hydrogen leaks. Every system has a bottleneck.

And then there’s the human factor. In NASA’s astronaut tests, crew members said getting in and out of rovers took over 4 minutes. That’s too long in an emergency. New designs cut that to 2.1 minutes. Science gear had to be reorganized - astronauts kept losing tools. Every detail matters.

Who’s Building What?

It’s not just NASA. The race is global.

- Intuitive Machines is leading with Moon RACER. They’ve tested in Arizona, validated by Apollo astronauts, and are on track for 2027 delivery.

- Astrobotic is developing mobility systems based on its Griffin lander, aiming for 2029 deployment.

- JAXA (Japan) is adapting its SLIM lunar lander into a mobility platform, with plans for a small rover by 2028.

- ESA and CNSA are working on their own systems - but so far, they’re not interoperable. That’s a problem. If a U.S. rover breaks down near a Chinese base, can they share parts? Not yet. The International Space Exploration Coordination Group is pushing for standard interfaces by 2030.

The market is exploding. In 2025, the global lunar robotics market was worth $1.2 billion. By 2035, it’s projected to hit $8.7 billion. NASA’s LTVS contract alone could pump $2.6 billion into the industry over the next decade.

What’s Next?

By 2028, the first unpressurized rovers will land. By 2030, pressurized vehicles might follow. Hoppers? Maybe 2035. But the real shift won’t be in hardware - it’ll be in how we use them.

Imagine this: A rover drops off a science team near a crater. It parks. A hopper launches from its back, flies 80 meters to a shadowed ridge, collects ice samples, lands, and returns. The rover loads the samples, drives back to base, and uploads data to the Lunar Gateway. All without human input.

That’s the future. Not just machines on the Moon - but a network of machines working together. And it’s closer than you think.

Can lunar rovers operate during the lunar night?

Yes, but only with advanced power systems. Solar panels don’t work during the 14-day lunar night, so vehicles rely on regenerative fuel cells or nuclear power sources. Moon RACER, for example, carries 200-300 kWh of stored energy, enough to run life support and navigation for days without sunlight. Thermal insulation and phase-change materials help retain heat, but prolonged darkness still limits operations.

Why are hoppers considered for lunar exploration?

Hoppers are designed to reach areas wheeled vehicles can’t - especially permanently shadowed craters where ice may exist. These regions are too steep or rocky for rovers, but a hopper can leap over obstacles, land precisely, and repeat the process. While still experimental, NASA and JAXA are testing small-scale prototypes that can jump 50-100 meters. They’re not meant to replace rovers, but to extend their reach.

How do lunar vehicles handle radiation?

Lunar radiation levels reach 200-400 mSv per year - far higher than Earth. Vehicles use radiation-hardened electronics rated for 100 krad total ionizing dose. Critical systems are shielded with materials like polyethylene and tungsten. Still, single-event upsets - where cosmic rays flip bits in computer memory - occur 3-5 times per 100 hours of operation. Redundant systems and error-correcting code help, but it remains one of the top technical risks.

What’s the difference between Moon RACER and a pressurized lunar vehicle?

Moon RACER is an unpressurized rover - astronauts ride outside in suits. It weighs 1,500-2,000 kg, travels 20 km, and costs $200-300 million to develop. A pressurized vehicle is a mobile habitat - astronauts live inside for days. It weighs 5,000-10,000 kg, covers 500-1,000 km, and costs $1.5-2 billion. Pressurized vehicles need larger landers and more power, but allow longer missions without spacesuits.

Will lunar mobility systems work on Mars?

Many technologies are being designed with Mars in mind. NASA’s STRIDE program, launched in 2025, is funding lunar mobility systems that can be adapted for Mars. The same autonomy software, dust mitigation techniques, and power systems being tested on the Moon will be used on Mars. The main differences? Mars has more atmosphere (helping with aerobraking), lower gravity (38% of Earth’s), and dust storms. But the core engineering challenges - radiation, autonomy, thermal control - are nearly identical.

Final Thoughts

The Moon isn’t just a destination anymore - it’s a workplace. And like any workplace, you need the right tools. Hoppers, rovers, and pressurized vehicles aren’t competing. They’re complementing each other. One carries tools. One carries people. One reaches the unreachable. Together, they’ll make lunar science possible - not just for weeks, but for decades.

16 Responses

Let me just say this: the idea that we can just "hop" across the Moon like it's a pogo stick arena is pure fantasy. You've got a system that needs to land with precision, fire thrusters in a vacuum, avoid craters, and do it all without real-time input? And you think dust won't gum up the thrusters? Apollo got lucky with their landings. This? This is a one-way ticket to a very expensive crater. I've seen too many prototypes fail in sims-real lunar regolith isn't just sand. It's glass shards with static cling. If you think a hopper can survive ten cycles without a catastrophic failure, you haven't been paying attention to the materials science papers from 2023. The thermal cycling alone will fatigue any alloy we've got. We're not ready. Not even close.

I get the skepticism, but we're talking about evolution here. Hoppers aren't meant to replace rovers-they're meant to extend them. Think of them as drones, but with legs. They don't need to be perfect. They just need to be good enough to get one sample from a permanently shadowed crater and relay it back. That's a win. We don't need a hundred hoppers. We need three. And if one fails? We learn. That's how innovation works. Moon RACER didn't start as a flawless machine either. It started as a prototype that couldn't climb a 30cm rock. Now it's doing 50cm. The same path is ahead for hoppers. We're not building a car. We're building a tool. Tools break. Tools improve.

Oh wow, I just read this whole thing and I'm so impressed! Honestly, I had no idea lunar dust was so dangerous-it's like the Moon is actively trying to sabotage us! I mean, imagine your car getting coated in this ultra-sharp, electrically charged powder that eats through seals and blurs your sensors? It's like nature's version of a hacker attack! And the fact that they're using electrodynamic shields? That's just genius! I'm so glad someone's finally thinking about this! I wish more people understood how fragile our tech is out there. Also, I think we should name the hoppers after astronauts. Like "Armstrong-1" or "Ride-2". It would be so cool. And I love how the article said "network of machines"-that's so poetic! I'm gonna share this with my book club. They're into space stuff. We're reading The Martian next week!

There's something quietly brilliant about how these systems are designed not to replace humans, but to amplify their reach. You don't need a person in every vehicle. You need a person in control of a network. That's the real shift-not hardware, but architecture. The Moon isn't a place you go to. It's a system you operate. And that changes everything. The fact that a rover can autonomously navigate 5km with 95% accuracy? That's not just engineering. That's a new kind of intelligence. We're not just sending tools. We're sending collaborators. And that's why this matters more than the shiny new rover specs.

so like... hoppers? really? like, jumping? on the moon? that sounds like something out of a 90s cartoon. i mean, sure, it's cool in theory, but have they tested it in a vacuum with actual lunar dust? because if the dust gets in the thruster nozzles, it's gonna be like trying to run a lawnmower through a sandstorm. also, who's gonna fix it if it breaks? you can't just call a mechanic out there. also, why not just use a drone? like, a drone with legs? that's what i'm saying.

eh, i read the first paragraph and got bored. too many numbers. just tell me if we're gonna have lunar taxis by 2030 or not. also, why does every article have to be 10 pages long? i just want to know if i can buy a moon scooter on amazon.

Let me just say this: "200-300 kWh of storage"? That’s not even a real number. It’s a range. And you say it’s enough to run for days? Days? How many? 3? 5? 7? You can’t just leave it hanging like that. Also, "80% less adhesion"? Less than what? Than Apollo? Than a potato? You’re not a scientist. You’re a marketing intern. And don’t even get me started on "autonomy software trained on 50,000 simulated lunar images." Simulated? From where? Who made the sims? Did they even include the 2022 dust storm data from LRO? No. Because you didn’t mention it. This article is a mess. Fix it. Or don’t publish it. But don’t pretend you’re informing anyone.

Let’s be honest here. This whole lunar mobility narrative is a distraction. NASA has been funding these projects for decades, and yet, here we are in 2025, still talking about "hoppers" and "electrodynamic shields" like they’re breakthroughs. But the real story? The real story is that the entire lunar program is being used to justify the continuation of the aerospace-industrial complex. Who profits? Lockheed. Boeing. Northrop. Not scientists. Not astronauts. Corporations. The $8.7 billion market projection? That’s not science. That’s a financial forecast written by consultants who’ve never seen a lunar regolith sample. And don’t tell me about "interoperability standards"-that’s just PR speak for "we’re not going to let China have a chance." This isn’t exploration. It’s colonialism with solar panels.

Actually, I think the pressurized vehicle part is underplayed. We’re talking about a mobile habitat that can sustain life for days-imagine doing geology for 72 hours straight without suits. That’s revolutionary. But the power issue? Yeah, it’s real. Solar won’t cut it. We need small modular nuclear reactors. Not big ones. Like, 5kW units, similar to what they use in submarines. Russia’s been testing them since 2020. Why isn’t NASA talking about this? Because they’re stuck in the solar-only mindset. We need to pivot. Fast. Also, dust shields? They’re great, but they don’t solve the problem of abrasion on bearings. We need ceramic-coated titanium, not just coatings. That’s the next step. And we’re not there yet.

I appreciate the depth of this article. It’s rare to see a piece that doesn’t just hype the tech but actually dives into the quiet, unsexy challenges-like the 4-minute entry/exit time for astronauts. That’s the kind of detail that makes or breaks a mission. I’ve worked in high-reliability systems before, and I can tell you: if you can’t get someone into a vehicle in under 90 seconds during an emergency, you’ve already lost. The fact that they cut it to 2.1 minutes? That’s not a minor win. That’s a triumph of human-centered design. And the thermal phase-change materials? Brilliant. Simple. Elegant. This is engineering at its best: solving problems no one asked for, because they knew they’d be the ones that killed you.

Look, I’m all for innovation, but let’s not pretend this isn’t a giant taxpayer-funded toy. We’ve been talking about lunar hoppers since the 90s. Why now? Because Elon’s got a rocket. Because Congress wants to look like they’re doing something. Real science? That’s happening in labs with funding that’s been cut in half. Meanwhile, we’re spending billions on a vehicle that might not even work. And don’t even get me started on the "network of machines" fantasy. You think a rover is gonna hand off a sample to a hopper? In real time? With 2.5-second lag? That’s not autonomy. That’s a death wish. We need to stop pretending we’re ready. We’re not. And pretending we are is the most dangerous thing of all.

I keep imagining these hoppers as lunar kangaroos-tiny, bouncy, awkward little machines leaping over craters like they’re auditioning for a space ballet. It’s absurd. It’s beautiful. And honestly? It’s the only thing that makes me feel hopeful. Because if we’re willing to build something this weird, this delicate, this *daring*… maybe we’re not just trying to survive out there. Maybe we’re trying to dance. And isn’t that what exploration is? Not just getting there. But finding wonder in the impossible. I don’t care if it fails. I just want to see it try.

so moon dust is bad? yeah i guess. but like… can’t you just wash it off? like with water? or air? idk. also i thought the moon had no air? so how does dust even stick? weird. also i like the hopping thing. it’s like a frog. cool.

Let’s not sugarcoat this: we’re building lunar vehicles with the same logic that got us the Ford Pinto. Radiation hardening? Hah. You think a $200M rover can handle 400 mSv/year? That’s a death sentence. And don’t get me started on the "interoperability" fairy tale. The Chinese are building their own moon base. The US? Still arguing over whether to use lithium-ion or fuel cells. Meanwhile, the Russians are quietly deploying nuclear-powered rovers. This isn’t exploration. It’s a geopolitical chess game where the pieces are made of titanium and the pawns are astronauts. And the media? They’re just the cheerleaders. Wake up.

This is incredible! Honestly, reading this made me so excited for the future. The fact that we’re building machines that can work together like a team? That’s the future. I’m not an engineer, but I can tell you this: when we finally see a hopper leap over a crater and come back with ice samples? That’s going to be one of the most beautiful moments in human history. We’re not just going to the Moon. We’re learning how to live out there. And that? That’s worth every dollar. Keep going. We believe in you.

And now we have the optimist. Cute. But let’s be real: if a hopper fails mid-leap, it doesn’t just "not deliver a sample." It becomes a kinetic projectile. At 10 m/s, with no atmosphere to slow it down, it hits the surface at 500+ Newtons of force. That’s enough to crater itself into the regolith. And if it lands on a slope? It rolls. Into a shadow. And freezes. And then what? We send another one? And another? And another? That’s not exploration. That’s a graveyard. And the worst part? We’ll call it "valuable data." We always do.