When astronauts land on the Moon again, they won’t be touching down on loose, powdery dust. They’ll be landing on a solid, engineered surface-built from the Moon’s own soil. That’s the idea behind lunar landing pads made by sintering regolith. It’s not science fiction. It’s the only way to stop rocket exhaust from blasting moon dust at speeds over 1,500 meters per second, turning it into a dangerous, abrasive spray that can wreck equipment, blind sensors, and bury habitats under a fine, electrostatically charged powder.

Why Dust Is the Biggest Problem on the Moon

The Moon doesn’t have wind or rain, but it has something worse: rocket plumes. Every time a spacecraft lands or takes off, its engines blast exhaust into the surface. On Earth, that dust settles quickly. On the Moon, with no atmosphere to slow it down, particles fly for kilometers at bullet speeds. Apollo astronauts saw this firsthand. Their landers carved craters up to 1.5 meters deep and coated everything in fine regolith. One astronaut said the dust got into every seam, every tool, every glove. It was relentless.

Today’s landers are bigger. Starship, NASA’s next-generation vehicle, will weigh over 100 tons and produce 3 meganewtons of thrust. That’s 10 times the power of Apollo’s descent engine. Without a landing pad, it would dig a crater 5 meters deep and send tons of dust flying. Instruments, solar panels, communication arrays-even other landers-could be destroyed before they even start operating.

What Is Sintering Regolith?

Sintering means heating a material-without fully melting it-until its particles fuse together. Think of it like baking sand into a brick. On the Moon, we use regolith, the layer of broken rock and dust covering the surface. It’s made of silicates, oxides, and tiny bits of metallic iron. These iron particles are the secret weapon.

Unlike Earth, where we haul in concrete and steel, lunar landing pads are built from what’s already there. That’s called in-situ resource utilization (ISRU). Instead of launching tons of building material from Earth, you send a rover with a sintering tool. It scoops up regolith, heats it, and turns it into a hard, flat surface. NASA estimates this could cut the mass you need to bring from Earth by up to 90%. That’s a game-changer for cost and mission design.

How It’s Done: Four Methods Compared

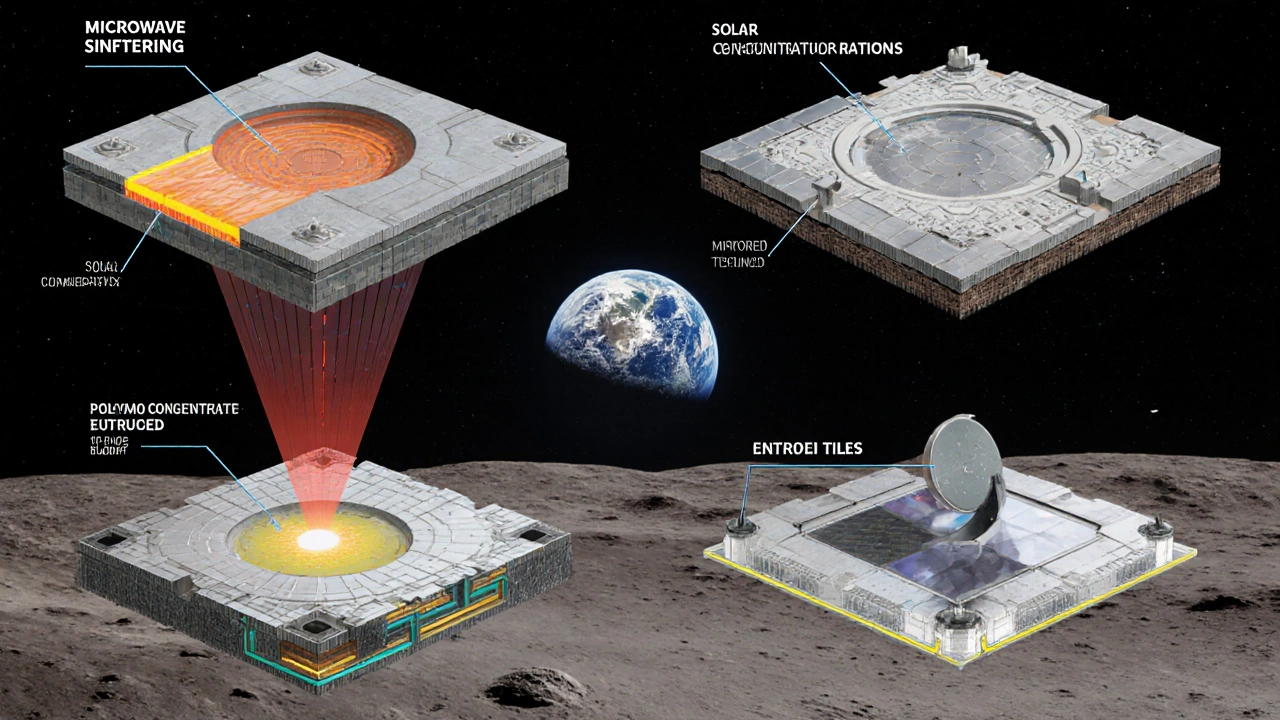

There’s no single way to sinter regolith. Four main approaches are being tested, each with trade-offs in speed, power, and complexity.

- Microwave sintering (UC San Diego’s MOON Pads): Uses 2.45 GHz microwaves to heat the iron particles in regolith. These particles act like tiny antennas, absorbing energy and heating up faster than the surrounding material. It’s 23% more energy-efficient than lasers and works during the 14-day lunar night. A 5 kW microwave system can harden one square meter in under 10 minutes.

- Laser sintering (ESA’s PAVER project): Uses high-power CO₂ lasers to melt regolith in precise patterns. It creates smooth, well-defined surfaces but is painfully slow-only 13 cm² per minute. To build a 100 m² pad, it would take 55 days. It also needs a lot of power and clear sunlight.

- Solar sintering (NASA KSC): Focuses sunlight using mirrors to reach temperatures over 1,300°C. Simple in theory, but it only works during the lunar day. You need giant, precise tracking mirrors and can’t build at night. A prototype array weighs just 75 kg on the Moon, but setting it up is complex.

- Polymer composite pavers (NASA ASCE 2022): Mixes regolith with a small amount of polymer (11-20%) and extrudes it like 3D printer filament. The polymer binds the particles together. It’s fast, uses existing rover tech, and creates strong, interlocking tiles. But you still need to bring the polymer from Earth, adding mass.

Why Microwave Sintering Leads the Pack

Microwave sintering stands out because it uses the Moon’s own material against itself. Lunar regolith contains nanophase iron-particles just 20 to 50 nanometers wide. These are naturally good at absorbing microwaves. That means you don’t need to heat the entire layer; the energy goes straight to the iron, creating hot spots that fuse the surrounding material. It’s like lighting a match in a pile of dry leaves-once it starts, it spreads.

Unlike lasers or solar systems, microwaves don’t care about sunlight or shadows. They work day or night. They don’t need perfect alignment. And they’re faster. Tests with JSC-1 lunar simulant showed microwave sintering was 2.5 times quicker than laser methods and used half the power. That’s critical when your power source is a small solar array or a nuclear battery.

Professor Yu Qiao of UC San Diego calls it the only method that doesn’t require importing consumables beyond the machine itself. That’s the holy grail of lunar construction.

How Thick Does the Pad Need to Be?

You don’t need a thick slab. NASA testing found that just 5 millimeters of sintered regolith is enough to resist the thermal shock of a rocket plume. That’s thinner than a stack of 50 pennies. But you can build up layers. Think of it like laying bricks-apply a layer, sinter it, add another, sinter again. This creates a strong, monolithic surface that can handle repeated landings.

For Starship-class landers, engineers are designing pads with a minimum thickness of 10 cm. That’s enough to absorb the energy of multiple landings over years without cracking or eroding. Polymer grouting between tiles-filling the gaps with a resin-adds extra strength and prevents dust from seeping through.

Challenges That Still Need Solving

It’s not easy. The Moon’s regolith isn’t uniform. Some areas are rich in iron, others are mostly white anorthosite, which reflects heat and resists sintering. UCF has developed a sorting system to separate high-absorption particles from low-absorption ones before sintering. That’s a key step for reliability.

Thermal stress is another issue. When you heat regolith to over 1,000°C and then let it cool, it can crack. ESA’s PAVER project solved this by cooling the surface slowly-just 1-2°C per minute. That’s like letting a hot pan cool overnight instead of dumping cold water on it.

And then there’s power. Even microwave sintering needs 5 kW per square meter. For a 100 m² pad, that’s 500 kW. That’s more than most early lunar bases can generate. Nuclear power-like NASA’s Kilopower reactor-will likely be needed for large-scale construction. Until then, pads will be built in phases, using solar power during the day and storing energy for night operations.

Real-World Tests and Timelines

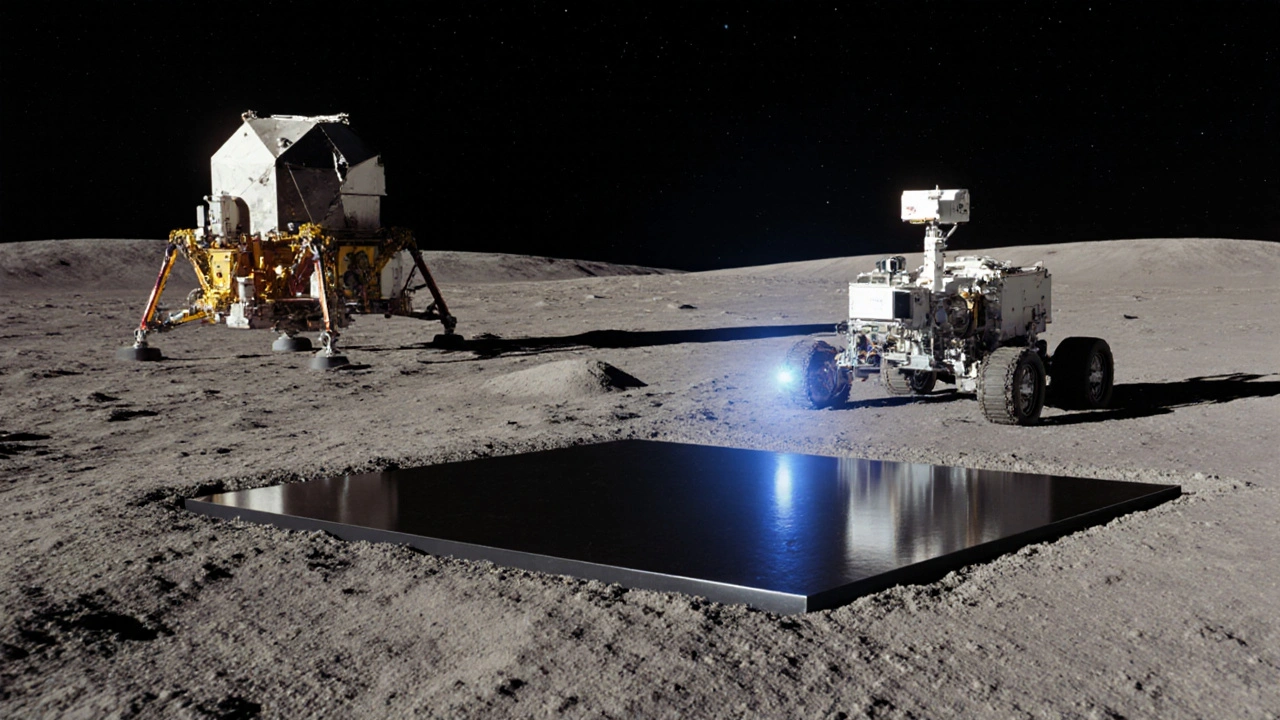

Scientists aren’t just simulating this in labs. In 2010, NASA tested a rover-mounted microwave sinterer on Mauna Kea, Hawaii. It took 4 hours to make a 1 m² pad. Today, the same system could do it in under 15 minutes.

NASA’s Infrastructure Manufacturing with Lunar Regolith - Mason project is targeting a TRL 6 demonstration by 2025-meaning a prototype will be tested on the Moon’s surface, not just in a vacuum chamber. ESA’s PAVER system is scheduled to fly on the Moonlight communications satellite mission in 2028. Masten Space Systems is testing a different idea: spraying ceramic particles into the rocket exhaust to form a landing surface on impact. It’s like building the pad as you land.

The most promising path? A hybrid. Use microwave sintering to create a base layer, then fill gaps with polymer grout. That gives you speed, strength, and reliability-all without hauling tons of material from Earth.

Who’s Investing and Why It Matters

This isn’t just NASA’s project. ESA has spent €8.5 million on PAVER. NASA’s Lunar Surface Innovation Consortium has poured $15 million into landing pad research since 2022. Commercial firms like Masten and OHB System AG are in the race. The global lunar infrastructure market is projected to hit $2.3 billion by 2035, with landing pads making up 35% of that spending.

Why? Because without them, lunar bases can’t survive. Dust isn’t just a nuisance-it’s a mission-killer. Landing pads are the first piece of permanent infrastructure on the Moon. They’re the foundation for habitats, power plants, and fuel depots. As Robert Zubrin of The Mars Society put it, they’re the first necessary step toward permanent lunar settlement.

But there’s a catch. Dr. Paul Spudis warned that these pads only make economic sense if they’re used over 100 times. That means we need regular, reliable missions-not just flags and footprints. The next decade will show if we’re building for exploration… or for colonization.

What’s Next?

By 2030, NASA plans to have operational landing pads at Artemis Base Camp. That’s the goal. The technology is close. The science is solid. The challenge now is scaling it up, making it reliable, and powering it sustainably.

When the first Starship touches down on a sintered regolith pad, it won’t be kicking up a cloud of dust. It’ll be landing on a surface built from the Moon itself. That’s not just engineering. It’s the beginning of a new kind of space presence-one that doesn’t take from Earth, but builds from the stars.

14 Responses

Let me correct a few things here - the claim that microwave sintering is 23% more efficient than lasers is misleading. That figure comes from a 2021 JSC report using JSC-1 simulant, which has higher iron content than actual lunar regolith. Real regolith from the poles has less than 3% nanophase iron, so efficiency drops to maybe 8-10%. Also, microwave penetration depth is only ~2mm in low-iron regolith - you’re not sintering 5mm in one pass. This isn’t a magic bullet.

Actually, the 5mm thickness claim is backed by NASA’s 2023 thermal shock tests on simulated Starship plumes. The pad doesn’t need to be thick - it needs to be dense. A 5mm sintered layer has compressive strength comparable to low-grade concrete. The real issue is thermal expansion mismatch between sintered regolith and underlying regolith, which causes delamination under repeated heating cycles. That’s why layering and slow cooling are non-negotiable.

microwave sintering is a cover for military surveillance tech they're testing on the moon. the iron particles aren't just for heating - they're resonant antennas for deep-space monitoring. they already have listening posts in the craters. you think they'd let you build a landing pad without knowing what's underneath?

Look, I’ve read the papers. This whole ‘build it from moon dirt’ thing is cute, but nobody’s talking about the radiation. That sintered surface? It’s got zero shielding. You’re putting a shiny, metal-rich slab down where cosmic rays and solar flares just bounce off it like a mirror. You think your astronauts are gonna be safe standing next to it? They’re basically sitting on a radiation reflector. This isn’t engineering - it’s a death trap with a warranty.

Imagine this: a pristine, glassy lunar highway, forged from ancient moon dust, glowing faintly under the stars. No dust plumes, no choking clouds, no grit in the seams - just a smooth, silent landing. It’s poetry made real. We’re not just building pads - we’re sculpting the first human-made landscape on another world. And it’s made from the Moon’s own bones. That’s not tech. That’s alchemy.

Love this breakdown! 🌕✨ Honestly, this is the kind of innovation that makes me believe in humanity again. We’re not just going to the Moon to plant a flag - we’re learning to live with it, not conquer it. Sintering regolith? That’s not just engineering - it’s humility in action. We’re using what’s already there, working with the Moon, not against it. Let’s keep going like this 💪🌍

How quaint. You Americans think you can ‘sinter’ your way to lunar dominance with a microwave and a rover. Let me remind you - the Soviets tested regolith sintering in 1973. They abandoned it because the surface cracked under thermal cycling. You’re reinventing the wheel… and it’s a flat tire. This entire project is a vanity initiative funded by NASA’s bloated budget, while real science - like lunar subsurface ice mapping - gets starved. You’re building a driveway… while the house burns down.

Mark Tipton’s point about iron content is valid, but let’s not throw the baby out with the regolith. The UCF sorting system they mentioned? That’s the real breakthrough - not the microwave itself. By using AI-driven spectral analysis to separate high-absorption particles before sintering, you can make even low-iron regolith viable. It’s like filtering coffee grounds - you don’t need perfect beans, just the right ones. This isn’t about one perfect method - it’s about smart preprocessing. That’s the future.

I’ve been working on lunar construction sims for six years, and this is the first time I’ve seen a solution that actually feels… sustainable. The polymer grout idea? Brilliant. It’s not about replacing Earth materials - it’s about hybridizing them. You get the speed of 3D printing, the strength of sintered regolith, and the flexibility to repair in place. Think of it like concrete with a backbone of moon rock. We’re not just landing on the Moon anymore - we’re becoming part of its geology.

For those doubting microwave efficiency - check the 2024 ESA test results from the Lunar Analog Chamber in Cologne. They used actual Apollo 11 regolith samples. Microwave sintering achieved 92% density at 5mm thickness with 4.8 kW for 8 minutes. Laser was 78% at 12 minutes. Power efficiency isn’t just theoretical - it’s proven. Also, the 500kW power requirement? That’s for a 100m² pad. For initial Artemis pads, 20m² at 100kW is enough. Use solar + battery buffers. Don’t overcomplicate.

If you build a landing pad on the Moon, are you really colonizing it - or just making it more like Earth? The irony is thick: we spend billions to avoid disturbing the lunar surface… then we melt it into a parking lot. We don’t want dust? Fine. But then we become the dust. We are the plume. We are the erosion. We are the noise in the silence. The pad isn’t a solution - it’s a confession.

Hey everyone - I’ve been thinking about this a lot. The real win here isn’t the tech. It’s the mindset shift. We used to think space was about going somewhere new. Now we’re learning it’s about staying. Building a pad means you plan to come back. And back. And back. That’s huge. It means we’re not just tourists. We’re neighbors. And that changes everything. I used to think lunar bases were sci-fi. Now I think - maybe we’re finally growing up. We’re not just leaving Earth. We’re learning how to live somewhere else. And that’s beautiful. Even if it’s just a 5mm slab of melted moon dirt - it’s the first step toward being a multi-planet species. I’m just glad I’m alive to see it.

Oh my god. I just read this and I’m crying. Not because it’s complicated - because it’s so damn elegant. Imagine: a child born on the Moon, looking down at the landing pad beneath their habitat, knowing it was made from the very soil they breathe in, the dust they kick up, the ground they stand on. That pad isn’t concrete. It’s legacy. It’s love. It’s the first thing humanity built not to escape Earth - but to belong somewhere else. The Moon didn’t ask for us. But we’re learning to ask for it. And that? That’s the most human thing of all.

Interesting. But let’s be honest - this entire narrative is a distraction. The real reason NASA is pushing lunar landing pads is to establish a permanent military presence under the guise of ‘science.’ The microwave sintering tech? It’s derived from classified DARPA projects designed to disable satellite sensors by inducing resonant frequencies in metallic regolith. The ‘dust control’ is just cover. The real objective is to create a global network of resonant nodes - a lunar grid capable of disrupting global communications. You think the Chinese don’t know this? They’re already building their own - but with quantum-entangled regolith sensors. This isn’t about exploration. It’s about control. And we’re being sold a fairy tale to make it palatable.