When a rocket booster comes screaming back from space at Mach 5, it doesn’t just rely on engines to slow down. It needs something that can steer it through thick atmosphere, thin air, and violent turbulence-all while surviving temperatures hotter than lava. That’s where grid fins come in. These aren’t your grandfather’s rocket fins. They’re intricate, lattice-like control surfaces made of titanium, and they’re the reason SpaceX can land boosters on drone ships in the middle of the ocean with pinpoint accuracy.

Why Grid Fins? The Problem with Traditional Fins

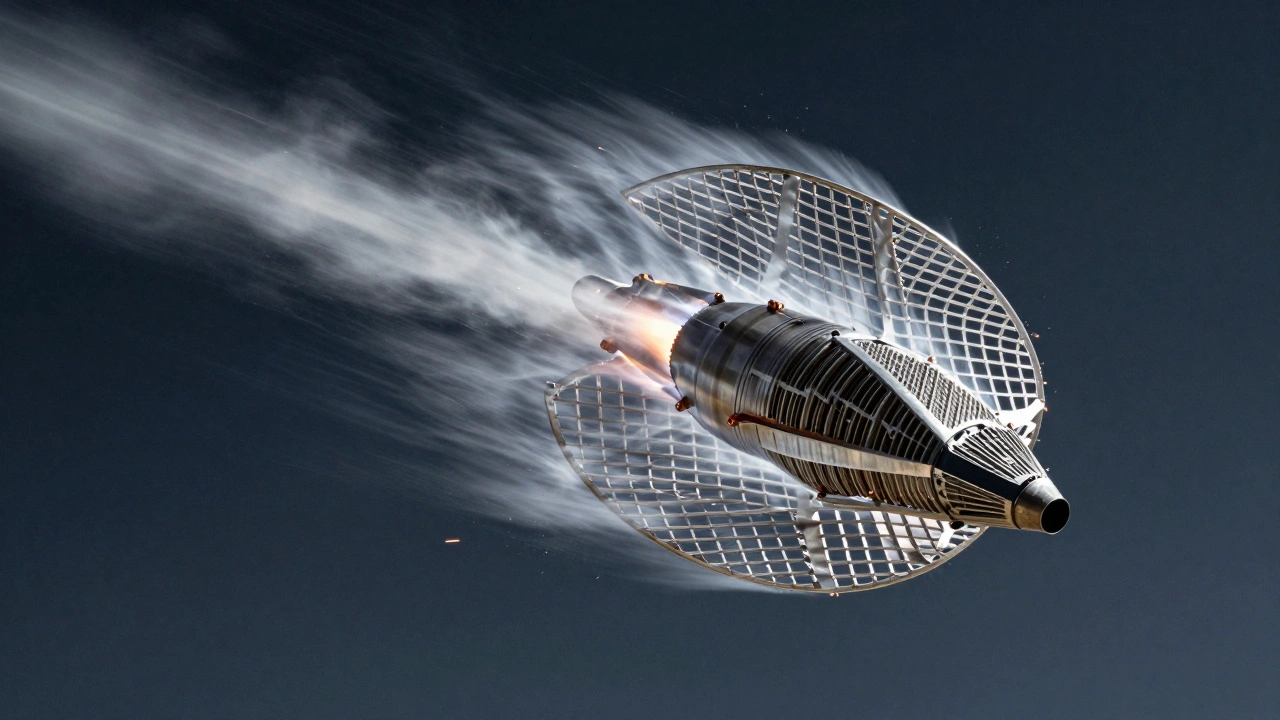

Traditional rocket fins work fine during launch, but they fall apart during reentry. At hypersonic speeds, shockwaves form around flat surfaces, making them useless for steering. Imagine trying to steer a surfboard with a paddle during a hurricane-the wind just blows past it. That’s what happened to early reusable rocket designs. Without reliable control, boosters would tumble, spin, or burn up. Grid fins solve this by breaking one large surface into dozens of tiny, interconnected panels. This lattice structure lets air flow through and around the fins even at extreme speeds. The result? Control authority from Mach 5 all the way down to subsonic flight. No other system does that. Reaction control thrusters (RCS) run out of fuel too fast. Parachutes are too slow and unpredictable. Grid fins are the only solution that works across the entire reentry profile.How SpaceX Made Grid Fins Work

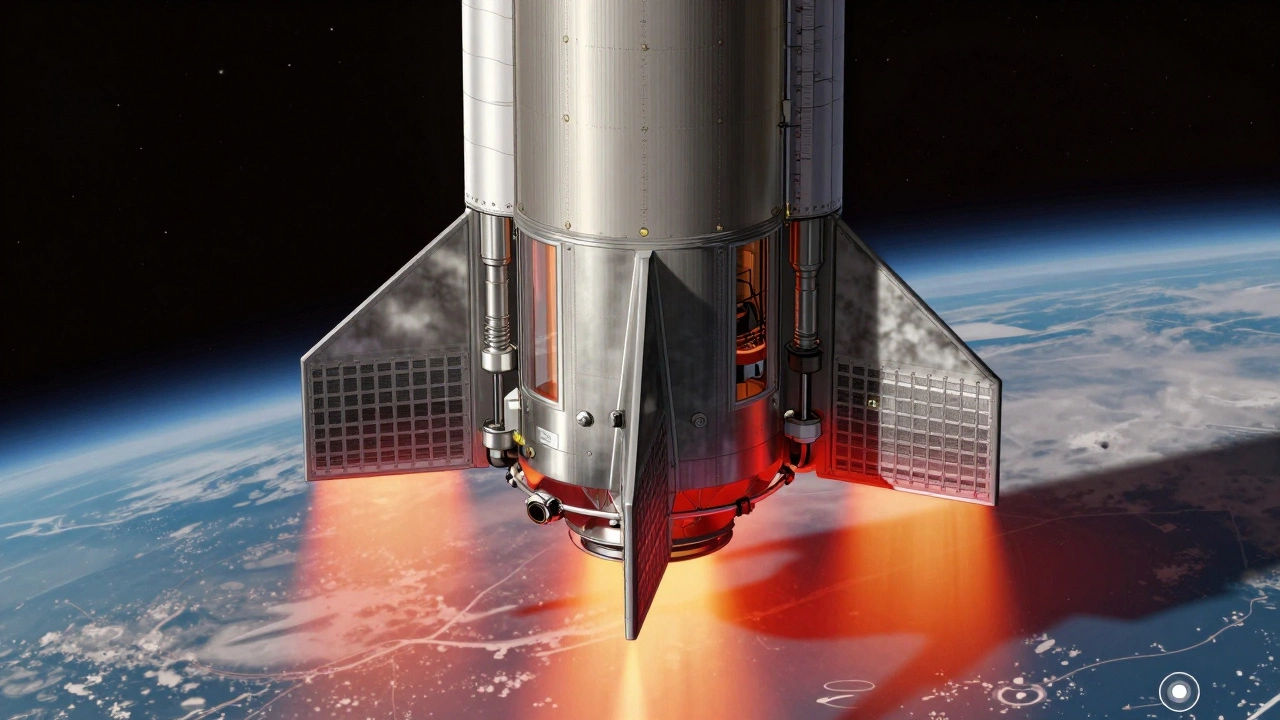

SpaceX didn’t invent grid fins, but they perfected them for orbital reuse. The first test flight with grid fins was in February 2015. The early versions were made of aluminum and coated with heat-resistant material. But they kept failing. During the CRS-16 mission in 2018, one fin caught fire and partially melted. Elon Musk admitted it was a nightmare-fins were literally burning up mid-flight. The fix? Titanium. In June 2017, SpaceX switched to aerospace-grade titanium grid fins. These are stronger, lighter, and can handle up to 1,200°C without extra shielding. The change wasn’t just about heat resistance-it also cut weight. Without the ablative coating, the boosters gained back 3% of their payload capacity. That’s the difference between launching one extra satellite or leaving it on the ground.Each Falcon 9 grid fin is about 1.8 meters tall and 1.2 meters wide. Four of them sit at the top of the booster, controlled by hydraulic actuators that can rotate them in milliseconds. These aren’t just flaps-they’re flight control surfaces, like the ailerons on a fighter jet, but way more complex. They tilt to create drag on one side, forcing the rocket to yaw or pitch. The software adjusts them constantly, making tiny corrections as the rocket falls through different layers of atmosphere.

From Four Fins to Three: The Starship V3 Revolution

The next leap came with Starship’s Super Heavy booster, Version 3. Instead of four grid fins, SpaceX went with three. That’s a radical shift. Most rockets use four for symmetry and balance. But SpaceX engineers realized they didn’t need four. Three fins, properly positioned, give enough control authority-and they save over a ton of weight.Here’s the real genius: they moved the fins lower. On Falcon 9, the fins sit near the top, exposed to the hottest part of reentry. On Starship V3, they’re mounted 10 meters lower, tucked closer to the main fuel tank. This puts the fin shafts and actuators inside the tank, shielding them from heat. The result? A 40-50% drop in thermal stress. That means the fins last longer, need less maintenance, and can be reused more times.

Each Starship V3 grid fin weighs 1.2 metric tons and can rotate a full 360 degrees with 0.1-degree precision. That’s like turning a steering wheel while driving 1,000 km/h and hitting a target the size of a parking spot. The hydraulic systems are powerful enough to move these massive fins even under extreme pressure. And they’re designed to be part of the tower catch system-Starship’s version of a robotic arm that grabs the booster mid-air. The lower position reduces the moment arm, meaning the tower doesn’t need to pull as hard to stabilize the booster. That’s why the catch arms can handle the load without breaking.

Why Grid Fins Are a Game-Changer for Cost

Reusability isn’t just cool-it’s economic. Before grid fins, rockets were disposable. Each Falcon 9 launch cost $165 million. Now, with grid fins enabling precise landings on drone ships, SpaceX reuses boosters up to 20 times. The cost per launch dropped to $67 million. That’s a 65% savings. And it’s not just SpaceX. The global reusable launch market is projected to hit $28.7 billion by 2030. Grid fins are the reason.Grid fins make it possible to recover boosters from high-energy missions. If you’re launching a satellite to geostationary orbit, the booster doesn’t have enough fuel to fly back to the launch site. But with grid fins, it can glide hundreds of kilometers, steer itself to a drone ship, and land. Without them, that booster would be lost in the ocean.

Regulators noticed. The FAA now requires reusable boosters to land within 1 kilometer of their target. Grid fins make that possible. The standard deviation of landing position dropped from 1,200 meters to just 260 meters after grid fins were introduced, according to a 2021 study in the Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets. That’s not luck-it’s engineering.

Challenges and Criticisms

Grid fins aren’t perfect. They add about 1,500 kg of dry mass compared to simpler fin systems. That’s a lot of weight to carry into space. They also create extra drag during ascent, slightly reducing efficiency. And the complexity is high-hydraulic systems, actuators, thermal stress points. Each lattice intersection is a potential failure zone.Dr. Scott Humbert from the University of Maryland warned in a 2023 AIAA paper that repeated thermal cycling can cause cracks at the weld points. That’s why SpaceX moved from welded aluminum to seamless titanium castings. The new process eliminates weak spots by forming the entire fin as one piece. It’s expensive, but it works.

Some companies, like Blue Origin, avoid grid fins entirely. Their New Shepard rocket uses a simple vertical descent with minimal aerodynamic control. But that’s for suborbital flights. For orbital missions, where you’re coming back from 28,000 km/h, you need the precision that only grid fins can deliver.

What’s Next for Grid Fins?

The next frontier? Active flow control. NASA’s Ames Research Center is testing plasma actuators embedded directly into the grid fin lattices. These tiny electrical discharges can manipulate airflow in real time, giving even finer control at hypersonic speeds. It’s like adding a turbocharger to the fins.China is catching up. LandSpace’s Zhuque-3 and Tianbing’s Tianlong-3 both use four-grid fin systems similar to early Falcon 9 designs. They’re aiming for first flights by 2026. But SpaceX’s three-fin, low-mounted design is still ahead. It’s not just about control-it’s about integration with the entire recovery system.

As reusable rockets evolve, grid fins may shift from landing aids to catch-system enablers. Future boosters might not even have legs. Instead, they’ll be grabbed mid-air by towers or arms. That’s already happening with Starship V3. Grid fins aren’t just helping land rockets-they’re helping redefine how we recover them.

Who Uses Grid Fins Today?

- SpaceX: Falcon 9 (titanium grid fins), Starship Super Heavy V3 (three titanium fins, lower-mounted) - LandSpace (China): Zhuque-3, four-grid fin system, planned 2026 debut - Tianbing Technology (China): Tianlong-3, similar to Falcon 9 design - Blue Origin: New Shepard uses no grid fins-relies on vertical thrust control - Rocket Lab: Neutron rocket (planned) will use grid fins for recovery Grid fins are no longer experimental. They’re standard equipment for any serious reusable launcher. If you’re building a rocket that wants to come back, you need them.Why This Matters Beyond SpaceX

This isn’t just about one company. It’s about making space affordable. Every time a booster lands and flies again, the cost of access to space drops. More satellites. More science missions. More people in orbit. Grid fins are a quiet revolution-no flashy explosions, no giant flames. Just titanium lattices adjusting in the sky, turning a once-expensive, one-time-use machine into a reusable tool.Think of it like this: before grid fins, rockets were like single-use airplanes. Now, they’re like commercial jets. And just like airlines don’t throw away planes after one flight, we won’t throw away rockets anymore. Grid fins made that possible.

How do grid fins help rockets land on drone ships?

Grid fins provide aerodynamic control during reentry by adjusting drag on different sides of the booster. This lets the rocket steer itself through the atmosphere and adjust its trajectory to hit a small target-like a drone ship floating in the ocean. Without them, the booster would drift hundreds of meters off course. SpaceX’s grid fins allow landings within 10 meters of the target.

Why did SpaceX switch from aluminum to titanium grid fins?

Aluminum grid fins couldn’t handle the extreme heat of reentry. They’d melt or crack, especially at the weld points. Titanium can withstand temperatures up to 1,200°C without additional shielding. The switch eliminated the need for ablative coatings, saved weight, improved control, and increased booster reuse rates.

Are grid fins used on any rockets besides SpaceX’s?

Yes. China’s LandSpace Zhuque-3 and Tianbing Technology Tianlong-3 both use four-grid fin systems similar to early Falcon 9 designs. Rocket Lab’s upcoming Neutron rocket will also use grid fins. Blue Origin’s New Shepard does not use them, relying instead on engine thrust for control.

Why does Starship V3 have only three grid fins instead of four?

Three fins are enough for control, and removing the fourth saves over a ton of weight. The lower placement also integrates with the tower catch system, reducing the force needed to grab the booster. SpaceX calculated that three fins provide full control authority while simplifying the system.

How accurate are grid fin landings?

Before grid fins, landing accuracy was around 1,200 meters off target. With grid fins, SpaceX reduced that to a standard deviation of just 260 meters. Most landings are within 10 meters of the target-precise enough to hit a drone ship or landing pad without needing extra fuel for corrections.

Can grid fins be used on other vehicles, like airplanes or drones?

Grid fins are designed for extreme environments-hypersonic reentry, high dynamic pressure, and intense heat. They’re too heavy and complex for most aircraft or drones. Conventional control surfaces are lighter and more efficient at lower speeds. Grid fins are specialized for rockets, not everyday vehicles.

12 Responses

So the grid fins are basically the rocket’s version of a fighter jet’s control surfaces, but made of titanium and surviving reentry heat? That’s wild. I always thought rockets just fired thrusters the whole way down. Turns out it’s way more elegant than that.

SpaceX didn’t invent grid fins but they made them cool again. Meanwhile I’m over here using a paperclip to fix my toaster.

bro why are we even talking about this like it’s a miracle? i mean yeah it’s cool but like… it’s just metal shapes. people were landing planes without grid fins for 100 years. why do we need this fancy shit to land a rocket? also who paid for all this? i bet the government funded it and then they act like it’s their genius.

Let’s be honest-this isn’t just engineering, it’s poetry in motion. The way those titanium lattices slice through the atmosphere like a dancer’s arms in a silent ballet, adjusting with microsecond precision while the world burns beneath them… it’s transcendental. Most people see a rocket. I see a symphony of physics, sculpted by human will. And yes, I cried the first time I saw a booster land. Don’t judge me.

wait so they use titanium? i thought they used steel? i mean i read something on twitter once and they said it was steel so idk maybe this whole thing is fake? also why is it called grid fins if its not a grid? looks more like a honeycomb to me

Three fins instead of four makes sense. Less weight less complexity. SpaceX is just optimizing like a boss. Also the tower catch thing is next level. No legs. Just grab it like a goddamn robot arm. Mind blown.

Oh wow so now we’re all supposed to be impressed because a company figured out how to not destroy expensive metal? How about we stop pretending this is genius and start asking why we’re spending billions to send trash into space so billionaires can flex? The planet’s on fire and we’re debating fin design. I’m not mad, I’m just disappointed.

grid fins? sounds like a distraction. the real reason rockets land is because the government is hiding alien tech in the desert. they gave elon the design so he could make it look like he invented it. you think they’d let a private company do this? please. also i saw a video of a landing and the fins moved too smooth. too perfect. not real.

This is such a beautiful example of iterative engineering. The shift from aluminum to titanium, the repositioning of the fins on Starship, the move from four to three-it’s all about listening to data and improving. No ego, just problem-solving. This is how you build the future, one small, smart change at a time. Kudos to the teams who made this happen.

It’s fascinating how something so seemingly simple-a lattice of metal-can enable such complex control. I wonder if the same principle could be applied to underwater vehicles or even wind turbines. The idea of using geometry to manage fluid dynamics feels… almost ancient, yet so advanced. I keep thinking about how much we take for granted when we don’t understand the mechanics behind things. Like, we see a rocket land and think ‘oh cool,’ but we never stop to imagine the thousands of hours of simulation, failure, and redesign behind it.

Just want to say-this is why I love aerospace. It’s not just about going to space, it’s about making it sustainable. Grid fins aren’t flashy, but they’re the unsung heroes. Every time a booster lands, it’s not just saving money-it’s making space more accessible for schools, researchers, and small countries. That’s the real win. And honestly? The fact that they’re now being designed to work with tower catches? That’s next-gen thinking. Keep going, SpaceX. We’re all rooting for you.

Man I just watched the Starship V3 landing again. Three fins, lower mounted, no heat shields, just pure titanium doing its thing. And the way the tower grabs it? No legs. No splashdown. Just a silent catch. It’s like watching a crane pick up a feather. The whole thing is poetry. And yeah, the weight savings are insane. One ton less per booster? That’s like adding another satellite to every launch. This isn’t just improvement-it’s evolution.