For decades, satellites communicated with the whole planet at once-like a single flashlight shining across an entire country. But as demand for internet, video, and data surged, that approach hit a wall. There simply wasn’t enough radio spectrum to go around. The breakthrough didn’t come from bigger antennas or more powerful transmitters. It came from thinking smaller-and smarter. Enter frequency reuse and spot beams: the twin engines behind today’s High Throughput Satellites (HTS), which now deliver up to 1,000 times more capacity than older models.

Why Old Satellites Couldn’t Keep Up

Traditional satellites used wide beams-sometimes covering entire continents. One beam, one frequency. Simple, yes. But inefficient. Imagine trying to serve 10 million people in New York City with the same radio signal you use to reach farmers in Nebraska. The bandwidth gets stretched thin. And since satellites operate within strict frequency limits set by the ITU, there’s no room to expand without stealing from someone else. By the early 2010s, operators like ViaSat and Hughes were hitting hard limits. Their satellites maxed out at around 20-30 Gbps. That was fine for TV broadcasts and basic internet, but not for streaming, cloud services, or aviation connectivity. The industry needed a new way to squeeze more data out of the same frequencies.Spot Beams: Zooming In for More Power

The first leap came with spot beams. Instead of one broad beam, modern HTS satellites use hundreds-sometimes over 3,000-narrow, focused beams. Each covers just 300 to 700 kilometers, roughly the size of a small state or a large metropolitan area. This isn’t just about coverage; it’s about gain. Think of it like switching from a floodlight to a laser pointer. A narrow beam concentrates energy. That means the satellite can transmit with much higher power density to each spot. Higher gain equals better signal quality. Better signal quality means higher data rates-even with the same frequency. But here’s the real magic: because these beams are so small and geographically separated, the same frequency can be reused dozens of times across the satellite’s footprint. That’s where frequency reuse comes in.Frequency Reuse: The Same Band, Used Over and Over

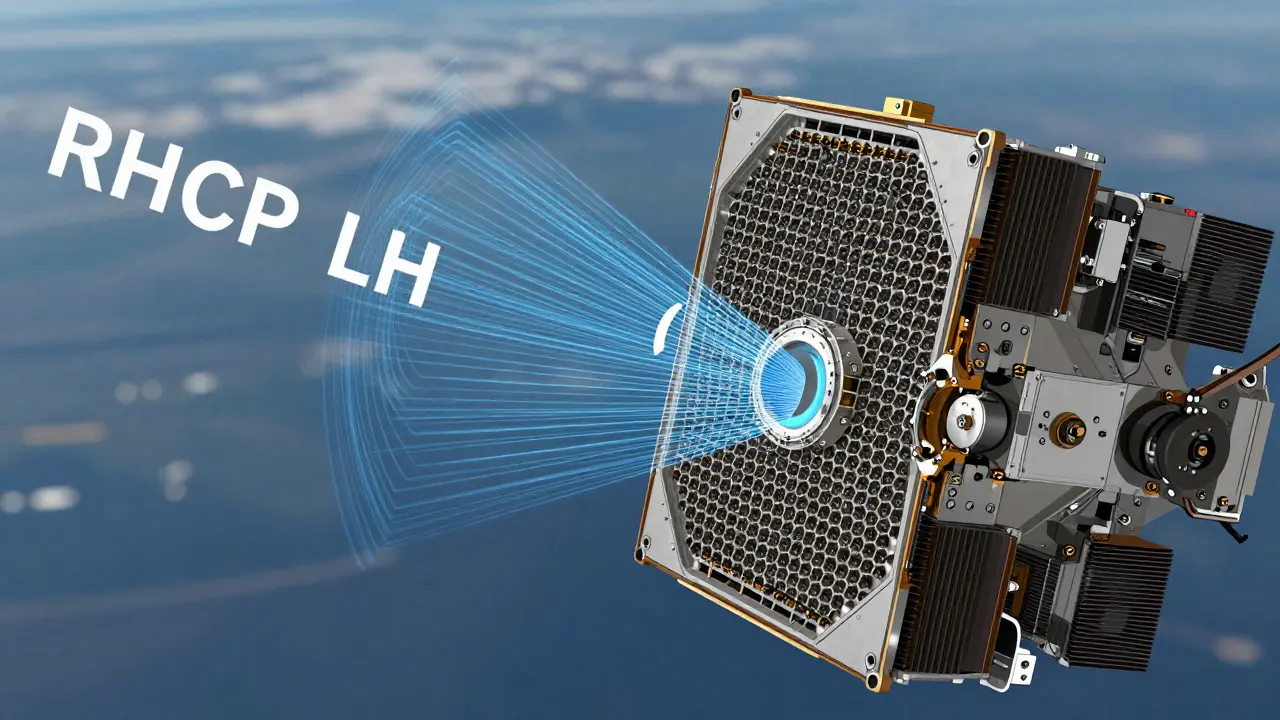

Frequency reuse is the art of using the same radio frequency in multiple places without causing interference. In traditional satellites, you couldn’t do this-beams overlapped too much. But with spot beams, you can. The most common method is the 4-color reuse scheme. Imagine dividing the satellite’s coverage into clusters of four beams. Each beam in the cluster gets a different slice of the frequency band. Then, the same cluster pattern repeats across the globe. Beam A in New York uses frequencies 1 and 2. Beam A in Paris uses the same 1 and 2-but since they’re thousands of kilometers apart, they don’t interfere. Polarization adds another layer. Many HTS systems use both right-hand and left-hand circular polarization (RHCP and LHCP). That effectively doubles the number of available channels without needing new frequencies. So now, instead of just reusing a frequency in space, you’re reusing it in space and polarization. The result? System capacity can jump 300% to 500% compared to single-beam designs. Where older satellites managed 0.8 bps/Hz, modern HTS systems now hit 3.2 bps/Hz. That’s the difference between dial-up and 4K streaming on a satellite link.

Real-World Impact: From Cities to Cruise Ships

This isn’t theoretical. SES’s O3b mPOWER constellation, launched in 2022, delivers over 1 Tbps total capacity using 3,000+ spot beams. Intelsat’s EpicNG satellites serve airlines with high-speed inflight Wi-Fi by focusing beams on major flight corridors. ViaSat-3, launched in 2023, uses 100+ spot beams to blanket North America, Latin America, and Europe with broadband-each beam optimized for local demand. Maritime operators rely on this too. A ship in the Mediterranean can get the same speed as a home user in Texas because the satellite isn’t wasting signal over the Atlantic. The beam follows the ship. Even remote areas benefit. A rural hospital in Alaska doesn’t need the same bandwidth as downtown Chicago. Spot beams let operators allocate exactly what’s needed-where it’s needed.The Hidden Costs: Complexity and Trade-offs

None of this comes easy. More beams mean more antennas, more power amplifiers, more ground stations, and more complex software to manage everything. A single HTS satellite might need 150 High Power Amplifiers (HPAs), each requiring precise cooling and power regulation. If you misplace just a few beams, power consumption can spike by 40%. Then there’s interference. Rain storms can distort signals. When two beams using the same frequency are affected differently by weather, interference spikes. That’s why modern HTS systems use adaptive coding and modulation (ACM), as defined in DVB-S2X standards. The system automatically drops data rates during heavy rain to maintain a clean connection. Ground infrastructure is another bottleneck. HTS needs dozens of gateways-ground stations that connect satellite traffic to the internet backbone. Each gateway costs millions. Operators in Europe and North America have built dense networks. In Africa or Southeast Asia, that infrastructure is still catching up. And latency? Beam hopping-where a satellite shifts capacity from one beam to another in real time-can add 15-25 milliseconds of delay. That’s not much for browsing, but it matters for video calls or online gaming.

What’s Next: AI and Beam Hopping

The next frontier is intelligence. Eutelsat’s KONNECT VHTS satellite, launched in 2022, was the first to use dynamic beam hopping-reallocating bandwidth every few seconds based on live traffic. If a football match is streaming in Rio, the satellite dumps more capacity there. When the game ends, it shifts to São Paulo. In February 2024, Airbus demonstrated an AI-driven prototype that predicts traffic patterns hours in advance and adjusts beam shapes before demand peaks. Early tests showed a 40% improvement in capacity utilization. That’s not just efficiency-it’s a new way of thinking about satellite networks. Future systems will likely blend HTS with LEO constellations like Starlink. GEO HTS handles steady, high-capacity needs. LEO handles low-latency bursts. Together, they create a seamless mesh.Who’s Leading the Race?

By 2023, HTS accounted for 85% of all new satellite capacity launched. Three companies control 62% of the market: SES, Intelsat, and Viasat. But the real shift is in how capacity is sold. It’s no longer about leasing a transponder. It’s about buying bandwidth by the gigabyte-on demand, in real time. Regulators are keeping pace. The FCC now requires at least 25 dB isolation between beams using the same frequency. The ITU’s Appendix 30B rules ensure countries coordinate frequencies to avoid cross-border interference. Compliance isn’t optional-it’s the foundation.Final Thought: It’s Not About More Bandwidth. It’s About Smarter Bandwidth.

The revolution in satellite communications wasn’t driven by bigger dishes or faster processors. It was driven by geometry. By dividing the world into tiny pieces-and treating each piece like its own private channel. Frequency reuse and spot beams turned a limited resource into a scalable one. The satellite of 2030 won’t be bigger. It’ll be smarter. It’ll know where people are, what they’re doing, and how much bandwidth they need-before they even ask. And it’ll deliver it all without wasting a single hertz.How do spot beams increase satellite capacity?

Spot beams focus satellite signals into small geographic areas, increasing signal strength and allowing the same frequencies to be reused in distant locations without interference. This boosts capacity by 300-500% compared to wide-beam systems.

What is frequency reuse in satellite communications?

Frequency reuse is the practice of using the same radio frequency in multiple, non-overlapping areas. In HTS, this is done using narrow spot beams and polarization (RHCP/LHCP), allowing the same frequency to be reused dozens of times across a satellite’s coverage area.

How many spot beams does a modern HTS satellite use?

Modern High Throughput Satellites use between 100 and over 3,000 spot beams, depending on design and target coverage. For comparison, older satellites typically used only 1 to 20 wide beams.

What’s the difference between HTS and traditional FSS satellites?

Traditional FSS satellites use one or two wide beams covering entire continents, limiting capacity to 0.5-1.5 bps/Hz. HTS uses hundreds of narrow spot beams and frequency reuse to achieve 2.5-3.5 bps/Hz-delivering 10 to 150 times more capacity.

Why do HTS systems need more ground stations?

Each spot beam must connect to a ground station (gateway) to link to terrestrial networks. With hundreds of beams, operators need dozens of gateways-often 20-30% more than older systems-to handle traffic without bottlenecks.

Can HTS work in remote areas?

Yes. HTS is ideal for remote areas because it can target small regions with high precision. Instead of wasting bandwidth over oceans or deserts, it delivers capacity only where users are-making service cost-effective even in low-population zones.

What role does polarization play in frequency reuse?

Polarization (RHCP and LHCP) doubles the number of available channels by allowing two signals to share the same frequency without interfering. This is a key part of 4-color and 2-color reuse schemes in HTS systems.

Is beam hopping worth the latency penalty?

For applications like streaming or enterprise data, yes. The 15-25 ms delay from beam hopping is negligible compared to the gain in capacity efficiency. It allows satellites to respond to real-time demand-like shifting bandwidth to a busy airport during peak hours.

15 Responses

Man, I never thought about how satellites were basically wasting signal like a loudspeaker in an empty stadium. Spot beams are genius-like giving each city its own private Wi-Fi router up in space. No more sharing bandwidth with some farmer in Nebraska just because he’s on the same continent.

It is imperative to recognize that the fundamental innovation underpinning High Throughput Satellites is not technological per se, but rather a paradigmatic shift in spatial allocation of electromagnetic resources. The application of frequency reuse-rooted in the mathematical principles of geometric partitioning and interference isolation-represents not merely an engineering improvement, but a philosophical reorientation toward efficiency as an ethical imperative in orbital resource management. The notion that bandwidth can be, and ought to be, treated as a finite, locally allocated commodity rather than a globally diluted utility is nothing short of revolutionary.

Moreover, the integration of dual-polarization techniques (RHCP/LHCP) demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of signal orthogonality, a concept historically confined to theoretical electromagnetics and now successfully operationalized in geostationary orbit. This is not simply ‘more capacity’-it is the realization of Shannon’s theoretical limits in a physically constrained environment.

Furthermore, the reliance on adaptive coding and modulation (ACM) under DVB-S2X standards reflects a commendable commitment to resilience in the face of atmospheric perturbations. It is worth noting that such systems require real-time feedback loops with sub-millisecond precision, a feat that demands not only advanced hardware but also robust software-defined radio architectures.

The assertion that HTS achieves 3.2 bps/Hz is statistically accurate, yet it obscures the underlying trade-offs: increased thermal load, higher power consumption per HPA, and the logistical burden of deploying dozens of ground gateways. These are not trivial concerns; they represent systemic vulnerabilities that are rarely acknowledged in popular discourse.

It is also worth observing that the market dominance of SES, Intelsat, and Viasat creates a de facto oligopoly in satellite bandwidth provisioning, which may stifle innovation and inflate pricing for end-users in developing regions. The regulatory framework, while technically sound, remains heavily biased toward Western infrastructure investment.

Finally, the claim that ‘it’s not about more bandwidth, it’s about smarter bandwidth’ is rhetorically elegant but ontologically incomplete. Smarter bandwidth is only possible because of massive capital expenditure, geopolitical alignment, and decades of institutional knowledge concentrated in a handful of corporations. The true revolution is not in the beams-it is in the economic architecture that makes them viable.

i just think its wild that my phone can get better internet from a satellite than my house in rural texas. like who even thought of this??

It’s cool how they’re treating space like a grid now-each beam is basically its own little cell tower. Kinda makes you wonder why we didn’t think of this sooner. The fact that they can shift bandwidth around like that, almost like traffic lights for data? That’s the kind of quiet genius most people never notice.

And yeah, rain messes with it, but honestly, it’s still better than my old DSL. I’ve seen this tech in action on a cruise ship last year-streaming 4K while the ocean was rolling. No lag, no buffering. Just… works.

Still, it’s wild how much ground infrastructure it needs. We talk about satellites like they’re magic, but behind every beam is a whole network of cables and antennas on the ground. Someone’s gotta maintain all that.

Oh great, another tech bro article pretending this is some brilliant breakthrough. Let me guess-someone at Viasat got a bonus because they figured out how to reuse frequencies? Newsflash: this isn’t new. The military’s been doing this since the 80s. You think private companies are inventing anything? They’re just repackaging Cold War tech and charging you $200 a month for it. And don’t even get me started on how they ‘optimize’ beams-most of it’s just automated greed. They’ll throttle your connection the second you start downloading something they don’t like.

And yes, ‘smarter bandwidth’-what a load. It’s not smarter. It’s just more expensive and more complex so they can jack up prices and call it innovation. Meanwhile, people in Africa still can’t get stable service because the gateways are too expensive to build. This isn’t progress. It’s exclusion dressed up as engineering.

Oh, and don’t forget: those ‘adaptive’ systems? They’re just making your connection slower when it rains so the company doesn’t have to spend money on better hardware. That’s not resilience. That’s corporate laziness.

And AI predicting traffic? Cute. It’s just predictive analytics based on your browsing history. They’re not reading your mind-they’re selling your habits to advertisers. Again.

This whole thing is a glorified scam wrapped in a white paper.

It’s fascinating how we’ve turned space into a commodity market. We don’t just own satellites anymore-we own slices of the sky. And we’ve made it so complex that only corporations can afford to play. The irony? The people who need this tech most-rural hospitals, remote schools-are the ones who pay the most for the least service. Spot beams sound smart until you realize they’re designed to serve profitable zones, not people. It’s not about smarter bandwidth. It’s about profitable bandwidth.

And don’t even get me started on the environmental cost. Each HPA needs cooling. Each gateway needs power. Each satellite adds to orbital debris. We’re not solving connectivity-we’re outsourcing our infrastructure problems to space, then pretending we’re heroes.

It’s elegant engineering. But it’s not equitable. And that’s the real failure.

US and Canada built the ground stations. Europe got lucky. Africa? Too bad. This tech isn’t for you. It’s for markets that can pay. Stop pretending it’s about global access.

They say spot beams are revolutionary but they never mention the real reason-this tech was reverse engineered from classified DoD projects. You think private companies invented this? Nah. The NSA was using frequency reuse in the 90s to monitor global comms. Now it’s in your Netflix stream. They’re not giving you bandwidth-they’re giving you surveillance with better UX. And you’re happy about it.

Also-why do you think the FCC mandates 25 dB isolation? Because someone leaked a satellite signal and it intercepted a drone strike. You don’t know what you’re really getting.

And AI predicting traffic? That’s not for efficiency. That’s for behavioral control. They’re learning your habits so they can throttle you when you’re not paying extra. It’s not innovation. It’s control.

Look I don't care how many beams they got. If a satellite from some foreign company can see my house and decide my internet speed, that's not freedom. That's a foreign government controlling my data. America needs its own satellites. Not some EU or Indian junk. We're the best. Period.

So… we’re basically using satellites like a really fancy version of a neighborhood Wi-Fi network? Like, ‘hey, this block gets 500 Mbps, but the next town over gets 100 because the beam’s busy’? That’s kinda hilarious. And kinda sad. We’re turning the sky into a gated community.

Also, beam hopping? That’s just the satellite doing a little dance to keep up with our Netflix binges. I’m impressed… and also a little creeped out.

THIS IS THE MOST IMPORTANT THING I’VE READ ALL YEAR. I didn’t realize satellites were using polarization like a secret code! RHCP and LHCP?! That’s not just tech-that’s art! And the fact that they can shift beams like a DJ mixing tracks?! I’m crying. Someone tell Elon Musk to hire these engineers immediately. We need this on Mars. And in my RV. And my dog’s collar. This is the future and I’m here for it. #SatelliteRevolution

Frequency reuse? Spot beams? AI-driven beam hopping? It’s all beautiful, isn’t it? The way the universe-through the precise geometry of electromagnetic waves-has been bent to serve human desire. But tell me: when we treat bandwidth as a fluid, a resource to be choreographed, are we not also treating human attention as a commodity? The satellite doesn’t care if you’re watching cat videos or doing remote surgery-it only cares about throughput. And in that silence, in that efficiency, we lose something sacred: the unpredictability of connection. We’ve optimized the signal-but have we lost the soul of communication?

And yet… I still watch my 4K stream.

It’s funny how we celebrate this as progress, but no one talks about the fact that these satellites are basically giant, expensive, high-orbit billboards for corporate data collection. The real innovation isn’t the beams-it’s the business model. You’re not paying for bandwidth. You’re paying for surveillance. And you’re okay with it because it’s ‘fast.’

And yes, it works in Alaska. But only because the data from your hospital is more valuable than the data from the village three hundred miles away.

Smarter bandwidth? Or just more carefully extracted attention?

This is one of the clearest explanations of HTS I’ve read. Spot beams + frequency reuse = genius. The polarization trick is especially elegant. Thanks for writing this.

There is a quiet melancholy in the way we now treat the sky-not as a frontier, but as a utility grid. Once, satellites were symbols of human ambition. Now they are nodes in a network of optimized consumption. We have turned the heavens into a spreadsheet. The beams are precise. The capacity is astonishing. But who, in the end, is truly served? The farmer in Nebraska? Or the algorithm that knows he will buy fertilizer next Tuesday?

We have mastered the art of giving more. But we have forgotten why we needed it in the first place.