Going outside your spaceship in the middle of space sounds like something out of a movie. But for astronauts, it’s a job - and it’s one that takes hundreds of hours of training before they ever float beyond the airlock. These missions, called extravehicular activities (EVAs), or spacewalks, are critical for repairing the International Space Station, installing new equipment, or conducting scientific experiments. But you can’t just step out into vacuum and hope for the best. Every movement, every tool grab, every emergency response is drilled into muscle memory long before launch.

Why Train Underwater?

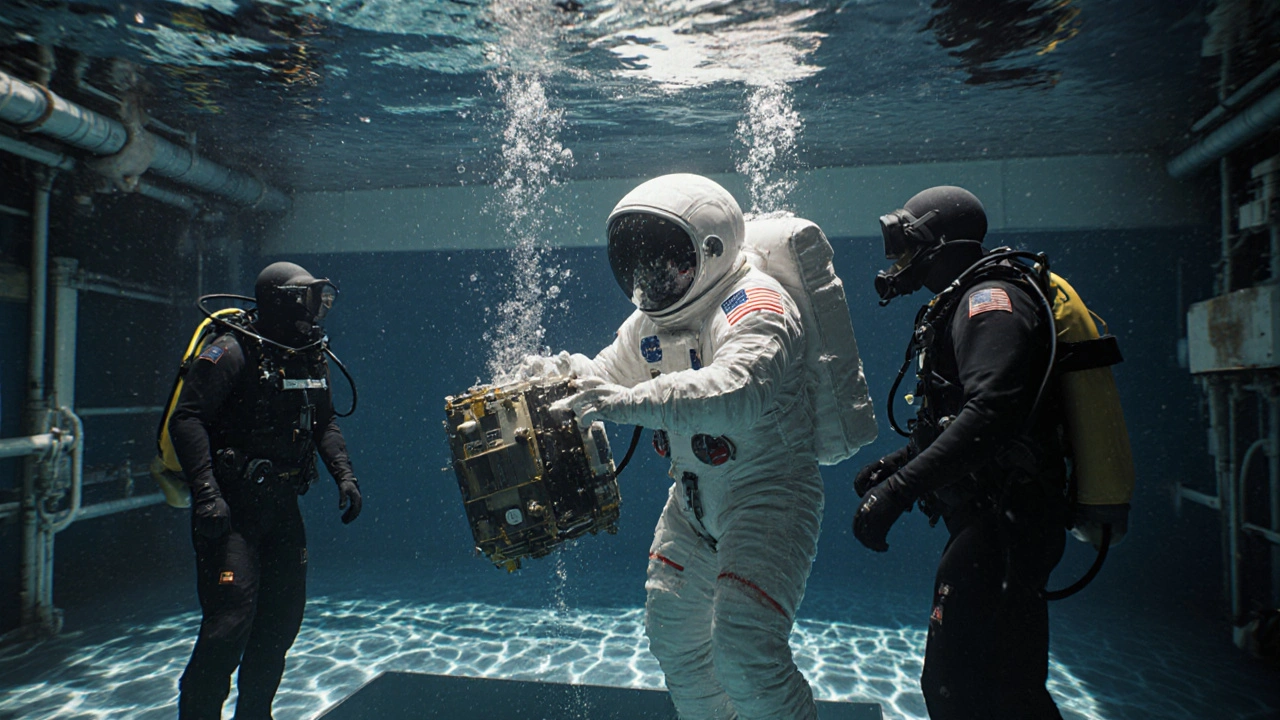

The most important place astronauts train for spacewalks isn’t a simulator or a VR headset - it’s a giant swimming pool. NASA’s Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory (NBL) at Johnson Space Center in Houston holds 6.2 million gallons of water. Inside, full-scale mockups of the ISS’s modules - including the Columbus lab, Japan’s Kibo, and sections of the station’s truss - sit submerged. Astronauts wear real, pressurized spacesuits, the same ones they’ll use in orbit, and spend hours moving through the water, practicing every task they’ll face in space.Why water? Because it’s the closest thing we have to zero gravity on Earth. When an astronaut and their suit are perfectly weighted, they don’t sink or float - they just hang there. This is called neutral buoyancy. It’s not perfect. Water creates drag, so movements feel slower. Gravity still pulls, just not as noticeably. But for the first time, astronauts can practice turning, reaching, twisting, and working with tools in a 3D environment that mimics the freedom of space better than anything else.

Each hour of actual spacewalk time requires five to seven hours in the pool. For a complex repair that might take four hours in orbit, an astronaut could spend 20 to 28 hours training underwater. That’s not just repetition - it’s precision. They learn how much force it takes to turn a bolt when the suit resists like a balloon full of air. They learn how to stabilize themselves without gravity to hold them down. They learn how to move without pushing off something solid - because in space, if you push, you go flying.

The Suit Is the Enemy - And the Lifeline

The spacesuit used for EVAs, called the Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU), weighs about 280 pounds on Earth. But underwater, with the right weighting, it feels weightless. That’s the trick. The suit is pressurized to 4.3 psi - enough to keep the astronaut alive in vacuum, but stiff enough to make every motion feel like moving through thick syrup. Imagine trying to type on a keyboard while wearing thick winter gloves. Now imagine doing it while floating upside down in a pool, with a helmet on, and no one else around to help if something goes wrong.That’s why divers are part of the team. Dozens of them - trained scuba professionals - swim alongside astronauts during training. They’re not there to coach. They’re there to save lives. If a suit leaks, if an astronaut gets tangled, if the oxygen supply drops, the divers are the first responders. Astronaut Christer Fuglesang, who’s done over 32 hours of spacewalks, put it plainly: “When you are underwater in a pressure suit like that, you are pretty, pretty helpless. So if something happens, you rely on the divers to get you safely out of the water.”

Training isn’t just about physical strength. It’s about endurance. Sessions last up to five hours - the same length as a real spacewalk. Astronauts practice the same breathing routine they’ll use before launch: wearing an oxygen mask for an hour before suiting up to flush nitrogen from their blood and avoid decompression sickness. They learn how to move with their arms and legs in a way that doesn’t waste energy. They learn how to use foot restraints - little anchors on the station’s exterior - to lock themselves in place while working.

Before the Pool: The European Prep Program

Not every astronaut arrives at the NBL ready to jump into the deep end. The European Astronaut Centre in Cologne, Germany, runs a preparatory course that NASA itself praised in a 2008 report as “innovative” and “highly effective.” This program doesn’t use full pressure suits. Instead, astronauts train in lightweight gear that still mimics the bulk and resistance of a real EMU. They learn the basics: how to handle tools, how to attach tethers, how to move between modules using handrails, how to clip into foot restraints.This prep work makes the NBL training far more efficient. Instead of spending hours learning how to hold a wrench, astronauts arrive at Houston already knowing how to move safely in a bulky suit. They can focus on the complex tasks - replacing a failed pump, rerouting a cable, installing a new solar array - rather than relearning the fundamentals. It’s like learning to ride a bike on training wheels before hitting the road.

Other space agencies, including JAXA and CSA, also use this model. It’s become standard practice: start simple, build confidence, then go deep. The NBL isn’t the beginning - it’s the final, high-stakes rehearsal.

Virtual Reality: The Digital Companion

While the pool builds physical muscle memory, virtual reality builds mental muscle memory. NASA’s VR system lets astronauts wear helmets with screens that show exactly what they’ll see during a spacewalk - the curve of Earth below, the station’s solar panels glinting in sunlight, the black void around them. Special gloves track hand movements, so when they reach for a tool, the system responds in real time.VR can simulate lighting conditions that are impossible to recreate underwater. In space, shadows are razor-sharp because there’s no atmosphere to scatter light. Sunlight hits one side of a module, and the other side disappears into total darkness. VR lets astronauts practice working in those conditions. It also lets them rehearse different orbital paths - what the station looks like from different angles, how the sun moves across the horizon.

But VR can’t replace the feel of resistance. You can’t simulate the weight of a tool in your gloved hand. You can’t feel the drag of a suit as you turn. You can’t practice how your body reacts when you push off a surface and start spinning. That’s why VR is a supplement - not a replacement.

What Happens When Things Go Wrong?

Spacewalks aren’t just about doing the job. They’re about surviving when things break. Training includes dozens of contingency scenarios. What if your suit loses pressure? What if your tether snaps? What if you get stuck in a tight spot and can’t reach the airlock?Astronauts practice emergency re-entry procedures. They learn how to use a SAFER jetpack - a small, backpack-like device with small thrusters - to maneuver back to the station if they drift away. They train for suit malfunctions, communication failures, and tool loss. In one drill, an astronaut might be told mid-task: “Your oxygen gauge is dropping. You have 10 minutes to get back.” They don’t panic. They’ve done it 20 times before.

These scenarios are brutal. They’re designed to be. Because in space, there’s no second chance. A mistake on Earth can be fixed. A mistake in orbit could be fatal.

Training for the Future: Beyond the ISS

The ISS is nearing the end of its life. By the early 2030s, it will be decommissioned. New commercial space stations are on the horizon - from Axiom Space to Blue Origin and others. These stations won’t look like the ISS. Their layouts, tools, and interfaces will be different.That means EVA training must evolve. The NBL will still be used - its physical realism is unmatched. But future training will need to adapt. NASA is already working on new mockups that reflect upcoming station designs. VR systems will be updated to simulate new environments. Training will become more modular, with astronauts practicing on digital twins of future stations before ever stepping into the pool.

One thing won’t change: the ratio. Five to seven hours of training for every one hour in space. That’s not just tradition - it’s the math of safety. Space is unforgiving. There’s no backup. No quick fix. No emergency crew rushing in. The only thing standing between an astronaut and disaster is the training they’ve done on Earth.

It’s Not Just About Strength - It’s About Patience

Most people think spacewalk training is about being strong. It’s not. It’s about being patient. It’s about moving slowly. It’s about thinking three steps ahead. In space, every motion has a reaction. Push too hard, and you spin. Move too fast, and you lose control. Pull a cable too hard, and you risk damaging something critical.Astronaut Ricky Arnold, who spent months on the ISS, said it best: “Extensive training on the ground helps prepare astronauts for spacewalks outside the station.” He didn’t say it was about being the strongest. He said it was about being prepared.

Every spacewalk is a performance. And like any great performance, it’s not about what happens on stage. It’s about what happened in the rehearsal room - the hours of silence, the sweat, the repetition, the fear, the focus.

There’s no shortcut. No app. No quick video. Just water, suits, divers, and the quiet determination of people who know that the next time they step outside, they won’t have a second chance.

How long do astronauts train for a single spacewalk?

Astronauts typically train five to seven hours in the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory for every one hour of actual spacewalk time. For a complex mission, that can mean spending over 100 hours underwater before launch. This includes practicing the exact tasks they’ll perform, as well as multiple emergency scenarios.

Why do astronauts train underwater instead of in zero gravity?

There’s no way to create true zero gravity on Earth for long periods. The Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory uses water to simulate weightlessness through neutral buoyancy - when an astronaut’s weight equals the water they displace. While it’s not perfect (water creates drag and gravity still pulls), it’s the closest and safest way to practice complex movements in a 3D environment before going to space.

What is the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory?

The Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory (NBL) is a massive indoor pool at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. It holds 6.2 million gallons of water and contains full-scale mockups of the International Space Station’s modules. Astronauts wear real spacesuits and train for spacewalks here, practicing everything from tool use to emergency procedures.

Do astronauts use virtual reality for spacewalk training?

Yes, but only as a supplement. NASA uses VR to simulate visual environments - like how the station looks from different angles or how shadows fall in sunlight. VR helps with spatial awareness and task planning, but it can’t replicate the physical resistance of a spacesuit or the sensation of moving in microgravity. That’s why the underwater training is still essential.

What role do scuba divers play in EVA training?

Scuba divers are critical for safety. Astronauts in pressurized suits are nearly helpless underwater - they can’t easily move on their own if something goes wrong. Divers monitor them constantly, assist with suit checks, help them reposition, and are ready to pull them out of the water in an emergency. They’re not trainers - they’re lifelines.

Is EVA training different for international astronauts?

Yes. Astronauts from ESA, JAXA, and CSA often complete a preparatory training program at the European Astronaut Centre before arriving at NASA’s NBL. This program teaches basic spacewalk protocols - like using tethers, moving along handrails, and attaching to foot restraints - using non-pressurized suits. This prep work makes their time in the NBL much more efficient and focused on advanced tasks.

12 Responses

India's space program is quietly building its own NBL-style training. We don't need to copy everything - just adapt what works. Our divers are trained too.

Wowzers. So we spend millions to train astronauts to do what? Fix a loose bolt while floating? And you call this science? I could do this in my bathtub with a garden hose and a helmet from Home Depot.

The part about divers being lifelines? That’s the most important detail. No one talks about that. These people risk their lives to keep astronauts safe during training. They deserve way more recognition.

Let’s be real - if we didn’t have the NBL, we’d be falling behind China and Russia. This is American ingenuity at its finest. No other country has the guts or the budget to build something like this. We lead because we train harder.

VR is cool, but it’s still a video game. The NBL? That’s the real deal. You feel the suit’s resistance, the drag, the weightlessness - it’s biomechanical muscle memory. That’s why NASA won’t replace it. It’s not tech - it’s tactile mastery.

It is truly remarkable how the discipline, patience, and meticulous preparation inherent in EVA training reflect the highest ideals of human endeavor. The dedication required to endure five hours in a pressurized suit, underwater, under constant supervision, speaks volumes about the character of those who undertake such missions.

I find it fascinating how the European prep program acts as a bridge. It’s not about replacing the NBL - it’s about layering competence. Like learning scales before playing a symphony. Makes me wonder if we could apply this to other high-risk professions.

There’s a typo in the third paragraph: ‘Inside, full-scale mockups of the ISS’s modules - including the Columbus lab, Japan’s Kibo, and sections of the station’s truss - sit submerged.’ - the sentence ends with a closing

tag that shouldn’t be there. Minor, but it breaks the flow.Interesting how the emotional weight of the training isn’t discussed. The fear. The isolation. The quiet dread before each dive. That’s the real invisible curriculum.

My cousin trained in Hyderabad for robotics. He said the hardest part wasn’t the tech - it was the silence. Same here. All that training, all that sweat - and then you just… float. Quiet. Alone. No one hears you.

It’s wild to think that every spacewalk is basically a rehearsal for a disaster… and yet, we do it anyway. I’m so grateful for these people. They’re not superheroes - they’re just humans who refused to quit. ❤️

Let’s be honest - if you’re not training in the NBL, you’re not serious. The Europeans? They’re doing preparatory yoga. The Americans? They’re forging steel in fire. This isn’t training - it’s initiation. And if you can’t handle five hours in a suit while drowning in water… you shouldn’t be near a rocket. Period.