When astronauts step outside the International Space Station, they’re not just doing repairs-they’re working in a place where a single mistake can kill them. There’s no air, no gravity, no second chances. Temperatures swing from -157°C to 121°C in minutes. Tools float away if you drop them. And if your suit leaks, you have minutes to get back inside. This isn’t a construction site. This is space. And every spacewalk-every Extravehicular Activity (EVA)-is the result of months of planning, simulation, and flawless coordination. EVA maintenance planning isn’t about getting the job done fast. It’s about making sure the astronaut comes home alive.

What EVA Maintenance Planning Actually Means

EVA maintenance planning is the process of designing every single action an astronaut will take during a spacewalk. It’s not just writing a checklist. It’s mapping out how they’ll move, what tools they’ll use, how they’ll communicate, and what happens if something goes wrong. Each EVA is built around a mission-critical task: replacing a broken pump, installing a new solar array, fixing a damaged antenna. But behind every task is a web of safety checks, backup plans, and simulations.Since the first U.S. spacewalk in 1965, NASA has turned EVA planning into a science. Today, planners use the EVA Planning and Execution Tool (a NASA-developed system that integrates real-time telemetry from space suits, orbital data, and 3D models of the ISS, EPET) to simulate every movement. They test how a wrench will behave in microgravity. They calculate how long it takes to reach a bolt 20 meters away while wearing a 120-kilogram suit. They model how radiation levels change as the station orbits over the poles.

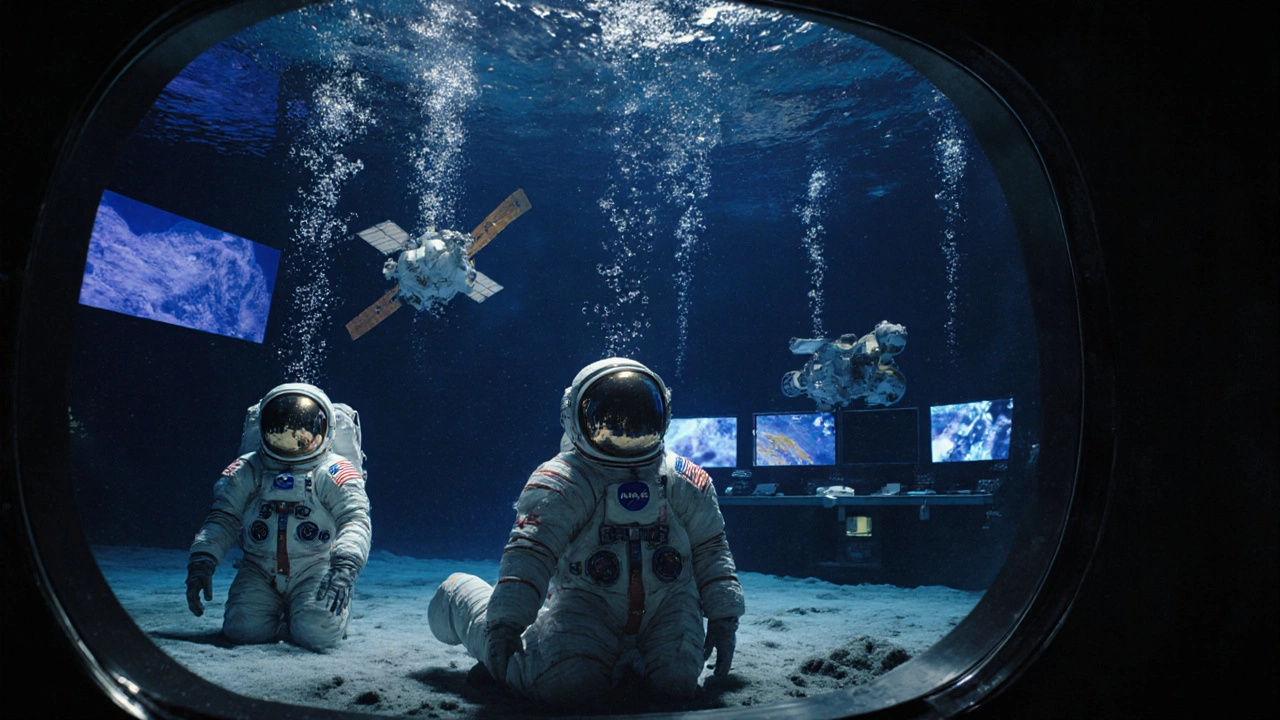

Unlike fixing a leaky pipe on Earth, where you can pause for coffee, an EVA has zero room for error. Once the hatch closes behind an astronaut, the plan is locked. You can’t call a timeout. You can’t swap tools. You can’t wait for better lighting. That’s why NASA now runs each EVA plan through 500+ hours of simulations in the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory-a giant pool that mimics weightlessness. Planners spend 78 hours preparing for every one hour of actual spacewalk time. That’s more than three full workweeks for a single six-hour mission.

Core Tools Used in EVA Planning

Planning a spacewalk isn’t done with pen and paper. It’s done with software that’s as complex as the spacecraft it supports. The current system, EVA Planning System (EVAPS) version 4.2 (NASA’s primary planning platform, updated in March 2023, featuring 3D VR modeling with 0.5mm precision and real-time suit telemetry integration), pulls data from dozens of sources:

- Space suit telemetry: Each EMU suit sends 128 data points per second-oxygen levels, CO2 concentration, suit pressure, battery charge, heart rate. If any value goes outside safe limits, the system can trigger an automatic abort.

- Orbital mechanics: The ISS moves at 28,000 km/h. Planners must account for when the station passes over ground stations, when communication drops out (90-minute blackouts over the South Pacific), and how sunlight angles affect visibility and temperature.

- 3D spacecraft models: Every bolt, panel, and cable on the ISS is modeled in VR. Planners walk through the virtual station in real time, testing reach, grip, and tool clearance. A tool that fits in a lab might jam in space.

- Contingency databases: The Gateway System (a pre-scripted response library for 147 failure scenarios, used since STS-109 in 2002) includes everything from a torn glove to a stuck bolt to a helmet leak. Each scenario has a step-by-step recovery plan.

These tools don’t just help with efficiency-they save lives. A 2022 NASA report showed that well-planned EVAs reduce task time by 22% and cut oxygen and battery use by 18%. That might not sound like much, but in space, every liter of oxygen counts. Every percent of battery life extends the window for survival.

Key Tasks Handled During EVA Maintenance

Not all spacewalks are the same. Some are quick fixes. Others are multi-hour assembly jobs. But all fall into three categories:

- Repair and Replacement: Fixing broken hardware. This includes replacing faulty pumps, swapping out degraded batteries, or installing new communication antennas. In 2020, astronauts replaced a failed ammonia pump module in a 7-hour EVA-the most complex repair ever done outside the ISS.

- Assembly and Upgrade: Building new systems. The ISS was assembled over 13 years with 167 EVAs. Each solar array, robotic arm, and science rack was installed during a spacewalk. These require precision alignment, torque control, and locking mechanisms that work in zero-g.

- Inspection and Testing: Checking for damage. After micrometeoroid strikes or debris warnings, astronauts conduct visual inspections. They use cameras, laser scanners, and tactile probes to assess hull integrity. In 2021, a small hole in the Soyuz module was found during an EVA inspection-planned just hours after the leak was detected.

Each task is broken into steps with strict time limits. A single bolt might take 15 minutes to loosen because of thermal expansion. A cable connector might need two astronauts working in tandem. Every action is timed, rehearsed, and validated. That’s why astronauts like Peggy Whitson, who did 10 spacewalks, say they practiced each move 200 times before the real thing.

Safety Protocols: The Non-Negotiables

Safety isn’t a step in the plan. It’s the entire plan.

Every EVA has two tethers. Each is rated for 5,000 pounds of force. Astronauts clip on before leaving the airlock and don’t unclip until they’re back inside. They carry a SAFER jetpack-a backpack with small thrusters-in case they float away. It’s never been used in an emergency, but it’s there.

Then there’s the suit. The EMU (Extravehicular Mobility Unit) has over 1,200 parts. It’s a mini-spacecraft. It keeps you alive. If the water cooling system fails, your body temperature can spike to dangerous levels in minutes. If the oxygen regulator jams, you suffocate. That’s why every EVA includes 15-minute contingency buffers (mandatory pause time built into every schedule per NASA SSP 50800 standard)-time to fix a problem, breathe, and reassess.

After the 2013 incident where astronaut Luca Parmitano nearly drowned when water filled his helmet, NASA added 23 new water intrusion scenarios to the contingency database. Before, they’d only planned for three. Now, every suit is tested under simulated leak conditions. Planners also monitor astronauts’ voice patterns and biometrics in real time. If stress spikes, mission control can pause the EVA-even if the task isn’t done.

And then there’s the cue card. After the Columbia disaster, NASA realized astronauts couldn’t read complex manuals inside their helmets. So they created the EVA Cue Card-a visual, step-by-step guide displayed on their helmet visor. It’s simple: icons, arrows, numbers. No text. 99.2% of astronauts understand it on first glance.

Why EVA Planning Is So Different from Earth-Based Maintenance

Think about a maintenance team fixing a wind turbine. They have tools, radios, spare parts, and the ability to stop and think. They can call a meeting. They can wait for daylight. They can walk away if it’s too hot.

In space, none of that exists. EVA planning operates under what NASA calls “Murphy’s Law on steroids.” If something can go wrong, it will-and it will kill you.

Industrial systems like UpKeep or eMaint focus on minimizing downtime. NASA’s system focuses on minimizing death. That’s why EVA planning has 327 safety checkpoints-up from 189 in 2010. That’s why every task has a backup plan. That’s why you can’t change 88% of the plan once the hatch closes.

On Earth, 68% of maintenance tasks can be adjusted mid-job. In space? Only 12%. That’s why astronauts train for years before they’re cleared to plan an EVA. New planners spend 15 to 20 EVAs under supervision before they’re trusted to write one on their own.

Challenges and Future of EVA Planning

Even with all this planning, space is unpredictable. In 2022, NASA aborted an EVA because a piece of space debris passed too close to the ISS. They had to wait 90 minutes for the station to clear the threat. Since 2010, 9 EVAs have been canceled due to debris warnings.

Another problem? Communication delay. On the ISS, mission control is just a few seconds away. But on the Moon, it’s 1.3 seconds. On Mars, it’s 20 minutes. That’s why NASA is developing Project AEGIS (an AI-driven planning tool scheduled for 2026, designed to reduce planning time by 40% using machine learning from past EVAs). It will suggest optimal tool sequences, predict suit wear, and auto-generate contingency plans based on historical data.

Commercial companies like Axiom Space and SpaceX are now entering the field. Axiom’s private missions to the ISS require their own EVA planning teams. SpaceX’s Starship plans for lunar EVAs by 2030 will need new tools-because lunar dust is abrasive, sticky, and can jam joints. Current EVA protocols only address 63% of dust-related risks.

And there’s a human problem: there are only 47 certified EVA planners in the world. NASA, ESA, Roscosmos, and CNSA share them. As Artemis missions ramp up, that number isn’t growing fast enough. Training one planner takes 18 to 24 months. And the knowledge is locked behind security clearances-78% of the procedures require top-secret access.

Final Thoughts: Planning as a Lifeline

EVA maintenance planning isn’t glamorous. No one sees the spreadsheets, the simulations, the 12,000-page documentation library. But every time an astronaut steps outside the airlock, they’re trusting every line of that plan. It’s not about efficiency. It’s not about speed. It’s about survival.

What looks like a simple repair is actually a symphony of precision engineering, human endurance, and unimaginable risk. The tools are advanced. The tasks are complex. But the safety protocols? They’re the real miracle.

As Dr. James Neuman, former head of NASA’s EVA Office, put it: “It’s not about wrench time. It’s about creating survivable pathways through lethal environments.” And that’s exactly what EVA planning does.

11 Responses

Just thinking about astronauts floating out there with nothing but a suit between them and the void... it makes me want to hug everyone I know. 🤗💙 Space isn't just science-it's courage wrapped in titanium and oxygen. We forget how much humanity is packed into every bolt they tighten up there. So much love for these unsung heroes.

Wait so you're telling me NASA didn't just make all this up to keep the budget flowing? 😏 What if the whole ISS is just a giant CGI set and the astronauts are actors? I mean, have you seen how perfectly those tools float? No gravity? No way. This is all a psyop to distract us from the real alien tech they're hiding.

Oh please. You call this 'planning'? This is overengineering dressed up as heroism. Real engineers don't need 500 hours of simulations for a six-hour job-they just fix things. The fact that you need 1,200-part suits and cue cards means you've already lost. If you can't handle space without a safety net the size of a small country, maybe you shouldn't go. This isn't bravery. It's institutional insecurity.

Just wanted to say: Sibusiso, you're wrong. This isn't overengineering-it's respect. Respect for the environment, for the human body, for the fact that death doesn't wait for a better day. Every tether, every backup, every emoji-laced tweet from Ronak? It's all part of the same thing: we care enough to plan for the worst so the best can happen. This isn't bureaucracy. It's love in engineering form.

I’ve always admired how NASA turns fear into structure. That’s the real genius here. They didn’t just build tools-they built rituals. The cue cards, the 15-minute buffers, the double tethers... these aren’t just procedures. They’re prayers made physical. It’s not about control. It’s about creating space-literal and emotional-for humans to survive in a place that doesn’t want them there.

Did you know the water cooling system in the EMU has a backup pump that activates if the primary fails? It’s not just redundant-it’s triple-redundant. And the suit’s thermal layer? It uses phase-change materials that absorb heat like a sponge. All this is public domain, but nobody talks about it. The real miracle isn’t the tech-it’s that we’ve made survival feel routine.

They talk about Murphy’s Law on steroids. But what if it’s not Murphy’s Law at all? What if it’s entropy? Space isn’t hostile-it’s indifferent. And planning? It’s just humanity’s desperate attempt to pretend it’s not. We simulate, we tether, we cue-card our way through the void because we can’t bear to admit we’re just meat in a tin can, screaming into the dark. The suit doesn’t save you. It just delays the inevitable.

It’s wild to think that somewhere in the world, someone spent 18 months learning how to plan for a 6-hour spacewalk. And then they spend another 200 hours training someone else to do it. And all of it-every spreadsheet, every VR simulation, every whispered contingency-is built around one simple truth: no one gets to come back if we get it wrong. That’s not just engineering. That’s sacred work. I’ve never seen a job where the margin for error is zero, and yet the stakes are so quiet, so ordinary, so human. We don’t cheer for the planners. But we owe them everything.

I cried when I read about Luca Parmitano’s helmet filling with water. Not because it was dangerous-though it was-but because they *changed everything* after that. They didn’t just patch it. They rewrote the rules. That’s not bureaucracy. That’s collective grief turned into action. Every single one of those 23 new water intrusion scenarios? That’s a mother, a child, a partner who almost lost someone-and then said, ‘Not again.’ That’s the quietest, most powerful kind of heroism.

Y’all are acting like this is Shakespearean tragedy. It’s not. It’s a goddamn checklist with a fancy name. ‘EVA Planning System v4.2’? Sounds like a Windows update. And ‘cue cards’? Bro, astronauts are reading emojis like they’re hieroglyphics. You know what’s more reliable? A laminated paper list taped to their thigh. No VR. No telemetry. Just ink. And if it breaks? They fix it with duct tape and prayer. That’s the real NASA. Not the corporate PR version.

Let me tell you something about Indian engineers who worked on EVA tools for ISRO’s Gaganyaan program-we didn’t have NASA’s budget, but we had something better: creativity under constraint. We redesigned a torque wrench using bicycle parts because the original was too heavy. We used smartphone cameras for inspection because we couldn’t afford space-grade optics. The point isn’t the tech-it’s the will. You don’t need 1,200 parts to keep someone alive. You need one thing: the refusal to let them die. That’s what every EVA planner does. They say ‘no’ to death, one simulation at a time.