Why Lunar Dust Is a Silent Killer for Solar Power on the Moon

Imagine a solar panel that loses half its power in just a few days-not from clouds or nightfall, but from fine, razor-sharp dust that sticks like glue. On the Moon, this isn’t science fiction. Lunar regolith dust, formed over billions of years by meteorite impacts, is nothing like Earth’s sand. It’s jagged, glassy, and electrostatically charged. When sunlight hits the Moon’s surface, that dust becomes positively charged. At night, electrons from space radiation make it cling even tighter. The result? Solar panels on lunar landers and rovers can lose up to 50% efficiency after just 1,000 hours of exposure, according to a 2022 study by Budzyn and colleagues.

This isn’t just a numbers problem. Dust clogs moving parts, wears down seals, disrupts thermal control systems, and if it gets inside habitats, it’s toxic to astronauts. Apollo astronauts reported dust sticking to their suits, scratching visors, and causing respiratory irritation. Now, with NASA’s Artemis program aiming for long-term lunar bases, dust mitigation isn’t optional-it’s mission-critical.

Active Solutions: Beams, Waves, and Electric Fields

There are two main strategies: active systems that clean the dust off, and passive ones that stop it from sticking in the first place. The most advanced active systems use electricity to push dust away without touching it.

The Electrodynamic Dust Shield (EDS), developed by NASA’s Carlos Calle, uses thin, transparent electrodes embedded into the solar panel surface. These electrodes create a traveling wave of electric fields that literally pushes dust particles off the panel. Tests in vacuum chambers using lunar simulant show it removes 75-90% of dust. In high vacuum-like on the Moon-it can hit nearly 100%. The system runs on just 2,000 volts at 20 hertz, and the electrodes are spaced just 1 millimeter apart. The catch? The transparent conductive material (Indium Tin Oxide) can reduce the panel’s efficiency by 2-3% right from the start.

Then there’s the Electron Beam Dust Mitigation (EBDM) system, which won NASA’s 2025 Dust Mitigation Challenge. Developed by LASP at the University of Colorado Boulder, EBDM fires low-energy electron beams (5-10 keV) at the dust. The electrons charge the particles, making them repel each other and the surface. In tests, it removed 92% of dust from solar panels, thermal blankets, and lenses. Unlike EDS, it doesn’t need electrodes built into the panel. That means it can be retrofitted onto existing hardware. The downside? It uses more power than EDS-about 0.2 Wh per square meter per cleaning cycle.

Both systems work better in lunar gravity than on Earth. Lower gravity means less force holding dust down. NASA’s Tom McCay confirmed that cleaning performance improves in low-G environments. That’s good news for the Moon.

Passive Defense: Coatings That Make Dust Slide Off

Active systems need power, control electronics, and maintenance. On a remote lunar base, reliability matters more than peak performance. That’s why passive coatings are gaining traction.

Researchers at the University of Central Florida (UCF), led by Lei Zhai, are developing nanoscale surface treatments that change how dust interacts with the panel. These coatings alter surface polarity, texture, and conductivity. Think of it like a non-stick pan-but for moon dust. In vacuum chamber tests with JSC-1A lunar simulant and UV radiation mimicking lunar day conditions, the coatings reduced initial dust adhesion by 60-70%. The dust that does land sticks less tightly, so even a gentle breeze from a lander’s exhaust or a small vibration can shake it loose.

The big advantage? Zero power needed. No moving parts. No risk of electrical failure. The downside? It doesn’t remove dust that’s already there. It only prevents new buildup. That’s why many experts now see passive coatings as a first line of defense, not a complete solution.

Other experimental coatings, like those using the Marangoni effect (where surface tension gradients move liquids), show promise but remain unproven under real lunar conditions. Carbon nanotube yarn electrodes are also being tested as flexible, lightweight alternatives to rigid copper strips in EDS systems-ideal for folding solar arrays on rovers or spacesuits.

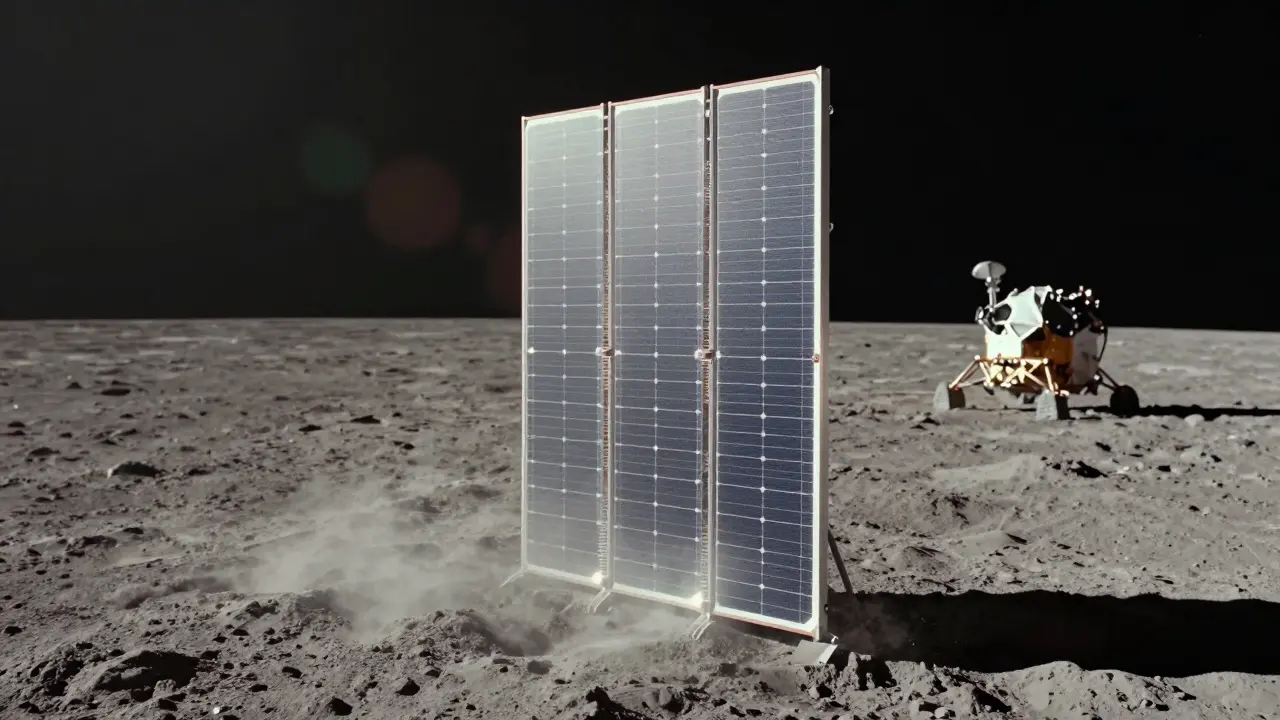

Vertical Arrays and the Hidden Problem of Landing Dust

One idea that sounded smart was putting solar panels on tall towers-10 meters high-so dust from landings wouldn’t reach them. But NASA’s DMFlex-ACO project found that’s not enough. When a lander touches down, it kicks up high-velocity dust that travels farther than expected. Even at 10 meters, vertical arrays still collect enough dust to cut power output by 20-30% over a 6-month mission.

That’s why vertical arrays aren’t a fix-they’re just a delay. They reduce dust accumulation by 30-40% compared to horizontal panels, but they still need cleaning. The real win? Combining height with passive coatings. A vertical panel with a non-stick surface gets the best of both worlds: less dust to begin with, and what does land, comes off easier.

Testing in the Lab: How Scientists Simulate the Moon

None of this works unless you test it under real lunar conditions. That’s why labs like UCF’s NanoScience Technology Center use vacuum chambers that drop pressure to 10-6 torr-close to the Moon’s near-vacuum. They don’t just blow dust on panels. They irradiate them with UV lamps to simulate solar charging, and use JSC-1A, a ground-made lunar simulant that matches the chemical and physical properties of real Moon dust.

They also use atomic force microscopy to watch individual dust particles stick and slide. And they’ve developed portable X-ray fluorescence (XRF) tools to analyze dust composition on-site. That’s crucial for Artemis missions: if a panel’s efficiency drops, you need to know if it’s dust, debris, or panel degradation. XRF gives you an instant answer.

One surprising finding? Dust adhesion spikes during lunar day due to UV charging and again during lunar night from electron bombardment. That means a cleaning system can’t just run once a day-it needs to adapt to the lunar cycle.

The Future: Hybrid Systems and Flight-Ready Prototypes

The next step isn’t choosing between active and passive-it’s combining them. NASA is already funding hybrid approaches. Imagine a solar panel coated with UCF’s non-stick nanomaterial, with thin EDS electrodes embedded along the edges. When dust builds up, a low-power pulse activates the electrodes. The coating makes the job easier. The system uses less energy. The panel lasts longer.

EBDM is now being built into a flight-ready prototype for integration with the Artemis IV lander, scheduled for September 2028. UCF’s coating tech received $2.3 million in 2023 funding. NASA’s 2026 budget for lunar dust mitigation jumped to $47.8 million-a 32% increase from 2024.

The goal isn’t just to keep panels clean. It’s to keep missions alive. A single lunar habitat needs 10-15 kW of power. Lose 20% of that to dust, and you lose life support, heating, or communication. That’s why this isn’t just engineering. It’s survival.

What’s Next for Lunar Power?

The next five years will see the first real-world tests of these systems on the Moon’s surface. NASA plans to deploy prototype dust mitigation units on the Artemis III and IV landers. If they work, they’ll become standard on every future lunar outpost.

But the real breakthrough will come when we stop treating dust as a problem to clean-and start treating it as a condition to design around. The best solution might not be a fancy beam or a smart coating. It might be a panel that doesn’t need cleaning at all.

Why is lunar dust so hard to remove compared to Earth dust?

Lunar dust is sharp, glassy, and electrostatically charged. Without wind or rain on the Moon, particles don’t get worn down. Solar radiation charges them during the day, and electrons from space radiation charge them at night, making them stick to surfaces like static cling on a balloon. On Earth, dust is rounded and washed away. On the Moon, it’s like tiny shards of broken glass glued to your solar panels.

Can regular cleaning methods like brushes or air blowers work on the Moon?

No. Brushes can scratch the delicate solar cells, and air blowers won’t work in the Moon’s vacuum. Even if you could blow air, there’s no atmosphere to carry the dust away. That’s why all viable methods rely on electrostatic forces-either pushing dust off with electric fields or charging it to make it repel the surface.

Do dust mitigation systems add significant weight to lunar landers?

Active systems like EDS or EBDM add minimal weight-mostly just the power electronics and thin electrodes or beam emitters. A full EDS system for a 10 m² panel adds less than 2 kg. Passive coatings add even less, often just nanometers of material. Weight is a concern, but the cost of losing power to dust is far higher. A 50% drop in solar output could mean losing a habitat’s heating system.

How long do these coatings and systems last?

Passive coatings are designed to last the entire mission-up to 10 years. They’re embedded into the panel surface and don’t degrade under UV or temperature swings. Active systems like EDS are built with durable materials, but their electrodes can wear over time. EBDM has no moving parts, so it’s more reliable long-term. NASA tests all systems for at least 1,000 lunar days (about 29 Earth months) before approval.

Is there a risk of dust damaging the cleaning systems themselves?

Yes. Abrasive dust can scratch electrodes or lenses if cleaning isn’t done properly. That’s why NASA avoids mechanical brushes. Even active systems must be carefully calibrated-too much power can damage the panel’s surface. The EBDM system was chosen partly because it doesn’t touch the surface at all. It’s a non-contact method, which reduces wear on both the dust and the panel.

14 Responses

Look, I’ve spent years working on lunar surface systems, and let me tell you-this dust problem is way worse than people realize. It’s not just about efficiency drops; it’s about system cascades. One panel failing leads to thermal runaway in adjacent modules, which then stresses the battery banks, and suddenly you’ve got a power brownout in a habitat. The EDS system is promising, but Indium Tin Oxide is brittle as hell in cryo-vacuum cycles. I’ve seen it flake after 300 cycles in simulated lunar nights. We need something more resilient, like graphene-reinforced transparent conductors. And passive coatings? Great, but they need to be tested under actual UV flux, not just lab lamps. Real lunar day UV is 10x stronger than anything we can mimic on Earth. We’re playing with fire if we assume these coatings will last a decade without degradation. We need in-situ monitoring, not just pre-launch validation.

Oh please. Another ‘lunar dust crisis’ narrative. You treat this like it’s the end of civilization. The Apollo astronauts survived with dust on their suits and visors. They didn’t have ‘EDS’ or ‘EBDM’-and they still walked on the Moon. This whole thing feels like a funding lottery for engineers who need to justify their grants. Let’s not forget: we sent men to the Moon with slide rules. Now we’re designing multi-million-dollar electrostatic dust vacuums for solar panels? Spare me. Maybe the real issue is that we’re over-engineering everything. Sometimes, a simple brush and a little extra panel area is all you need. Not every problem needs a PhD-level solution.

Okay, so let me get this straight-you’re telling me we spent billions to go back to the Moon, and the #1 problem is… dust? Like, literal dirt? And we’re talking about 2-3% efficiency loss from EDS coatings? Are you kidding me? That’s less than what you lose from a single fingerprint on a phone screen. And EBDM uses 0.2 Wh per square meter? That’s less than your phone charger uses in 30 seconds. We’re treating this like a doomsday scenario when it’s basically a maintenance annoyance. Also, ‘lunar regolith is razor-sharp’-duh. It’s been bombarded by micrometeorites for 4 billion years. We didn’t need a 2022 study to tell us that. This whole post reads like a grant proposal dressed up as journalism. Someone get these people a thesaurus and a reality check.

Let’s not romanticize the ‘non-stick pan’ analogy. That’s a gross oversimplification. Surface polarity? Nanotexturing? Please. We’re talking about a regolith composed of silicate shards, metallic iron nanoparticles, and amorphous glass-all charged to kilovolt potentials. A ‘non-stick’ coating is a fantasy until it’s proven under 14-day thermal cycles, 1000+ hours of UV flux, and micrometeoroid bombardment. And don’t even get me started on the ‘hybrid’ nonsense. Hybrid systems are the engineering equivalent of putting duct tape on a fusion reactor. They’re not elegant. They’re just more failure points. If you want reliability, go passive. If you want performance, go active. Don’t marry them. It’ll end in tears.

This is actually really encouraging. We’ve come so far since Apollo. The fact that we’re even thinking about long-term lunar infrastructure means we’re serious about building a future out there. The tech being developed here-coatings, electrostatic systems, even the XRF tools-isn’t just for the Moon. It’s going to help with Mars missions, asteroid mining, even satellite maintenance in low-Earth orbit. Every step forward, no matter how small, is a win. We’re not just solving a dust problem. We’re building the foundation for humanity to live beyond Earth. And that’s worth every watt of power we save.

What if we’re asking the wrong question? Instead of ‘how do we remove the dust,’ maybe we should ask ‘why do we need flat, horizontal solar panels at all?’ The Moon doesn’t have an atmosphere. There’s no weather. No wind. No rain. So why mimic Earth’s solar farm design? What if the most elegant solution is to abandon panels entirely and go with thermoelectric generators powered by the day-night thermal gradient? Or use lunar regolith itself as a thermal battery, storing heat during the day and converting it to electricity at night? We’re so focused on cleaning that we’ve forgotten to reimagine the system. Maybe the dust isn’t the problem-it’s our assumptions.

I appreciate the depth of research presented here. The technical details regarding electrostatic charging mechanisms and simulant testing protocols are both thorough and well-cited. However, I would respectfully suggest that the emphasis on active systems may inadvertently overshadow the potential of passive approaches. In environments where maintenance is impossible and failure is catastrophic, simplicity is not a compromise-it is a necessity. Passive coatings, even if they only reduce adhesion by 60-70%, represent a fundamental shift toward resilience. They require no power, no control algorithms, no moving parts. They are, in essence, a form of engineering humility. Perhaps the most advanced solution is the one that asks least of the system.

On Earth we clean solar panels with water. On Moon? We clean with physics. Simple. Brilliant.

Wow. So we spent 100 billion to go back to the Moon and the biggest innovation is… a way to keep dust off solar panels? I mean, congrats? You solved the problem of… dirt. Did we really need a 47 million dollar budget to figure out that dust sticks to stuff? I could’ve told you that in kindergarten. Also, ‘toxic to astronauts’? Really? You mean like the same dust that Apollo crews breathed in and lived to tell the tale? This feels like fearmongering dressed up as science. Someone’s getting a grant. Someone’s getting a TED Talk. Someone’s getting a book deal. Meanwhile, the rest of us are just here wondering why we’re still talking about dust in 2028.

EBDM is the real winner here. No contact. No degradation. No fragile electrodes. Retrofitting existing hardware? That’s the kind of innovation that scales. And yes, it uses more power-but compared to the cost of losing half your power output? It’s a bargain. We’re not talking about saving pennies. We’re talking about keeping life support alive. If you can clean a panel with 0.2 Wh and avoid a habitat shutdown, that’s not expensive. That’s smart. Stop overthinking it. The tech works. Deploy it.

It’s important to recognize that every innovation in lunar dust mitigation carries ethical weight. The technology we develop here will set precedents for extraterrestrial resource use, planetary protection, and human safety in space. We must ensure that these systems are not only effective but also equitable-accessible to international partners, not just those with deep NASA budgets. The future of lunar exploration must be inclusive, and that includes sharing the tools that keep our astronauts alive. Let’s not let cost or competition dictate who gets to survive on the Moon.

Is there any data on how dust accumulation varies between polar and equatorial regions? The lunar poles have permanently shadowed craters and extended sunlight periods-does that change the charging dynamics? Also, what about dust behavior during solar flares? High-energy particles could drastically alter electrostatic behavior. I’d love to see more on environmental variables beyond standard JSC-1A testing.

Good read. The hybrid approach makes sense. Coating first, then light EDS pulses only when needed. Less power, longer life. We’ve done similar things in desert solar farms-dust buildup is bad there too. But on the Moon, you can’t just hose it down. So yeah, physics over water. Smart.

This is actually kind of beautiful… like nature’s version of a sticky note, but on a planetary scale. The Moon’s dust is just… doing what it’s always done. And now we’re trying to outsmart it with science. I love that. We’re not fighting the Moon-we’re learning its language. And the fact that we’re designing systems that work with physics instead of against it? That’s the kind of progress that lasts. I’m so proud of the people working on this. You’re not just fixing panels. You’re making space feel a little more like home.