The Moon's Mystery: Why We Always See the Same Face

Most people have glanced up at the night sky, spotted the moon, and maybe even pointed out its familiar "Man in the Moon" or rabbit shapes. It feels like an old friend, right? But here’s something most folks don’t realize: you never, ever see the dark side of the moon from Earth. No matter where you live or how long you look, the moon is a cosmic tease, always turning the same face toward you. Strange? It gets weirder. The reason for this celestial one-sidedness is called synchronous rotation or tidal locking. Basically, the moon spins around its own axis at exactly the same rate that it orbits Earth—one spin every 27.3 days. So, as it travels its orbital path, that near side, all pockmarked and memorably grumpy, keeps staring back at us, while the far side stays hidden.

If you’re trying to picture this, grab a coffee mug and walk in a circle around a table while keeping the handle pointed at the table’s center. That’s how the moon moves. Tidal forces from Earth’s gravity slowed and synced up the moon’s rotation millions of years ago, making it impossible for us to sneak a peek at the "dark" side unless we leave Earth’s surface. So, despite what Pink Floyd says, it’s less about darkness and more about hidden angles. Both sides get sunlight during each month—the "dark" side is just mysterious because it’s hidden from direct view.

This tidal lock isn’t unique to our moon, by the way. It happens to other moons around Jupiter and Saturn. But the fact that it happened with our own moon, a mere 384,400 kilometers (about 238,855 miles) away, gives us front-row seats to a cosmic magic trick. No telescope on Earth, not even the fanciest one, can break this spell. You can catch lunar phases as the sun’s light shifts across its surface, but the far side? Total no-show. For generations, folks thought maybe there were seas, volcanoes, or even moon men over there. We had no idea until rockets came along.

But don’t mix up “dark side” with never-ever-lit-up. The far side gets just as much sunlight as the side we know, it just happens at opposite times. When it’s new moon for us (when we can’t see the moon at all), the far side’s having a full moon party. So, the phrase “dark side of the moon” is totally misleading. It only stays dark to human eyes on Earth—not to the sun.

From Legends to Lights: How We Discovered the Far Side

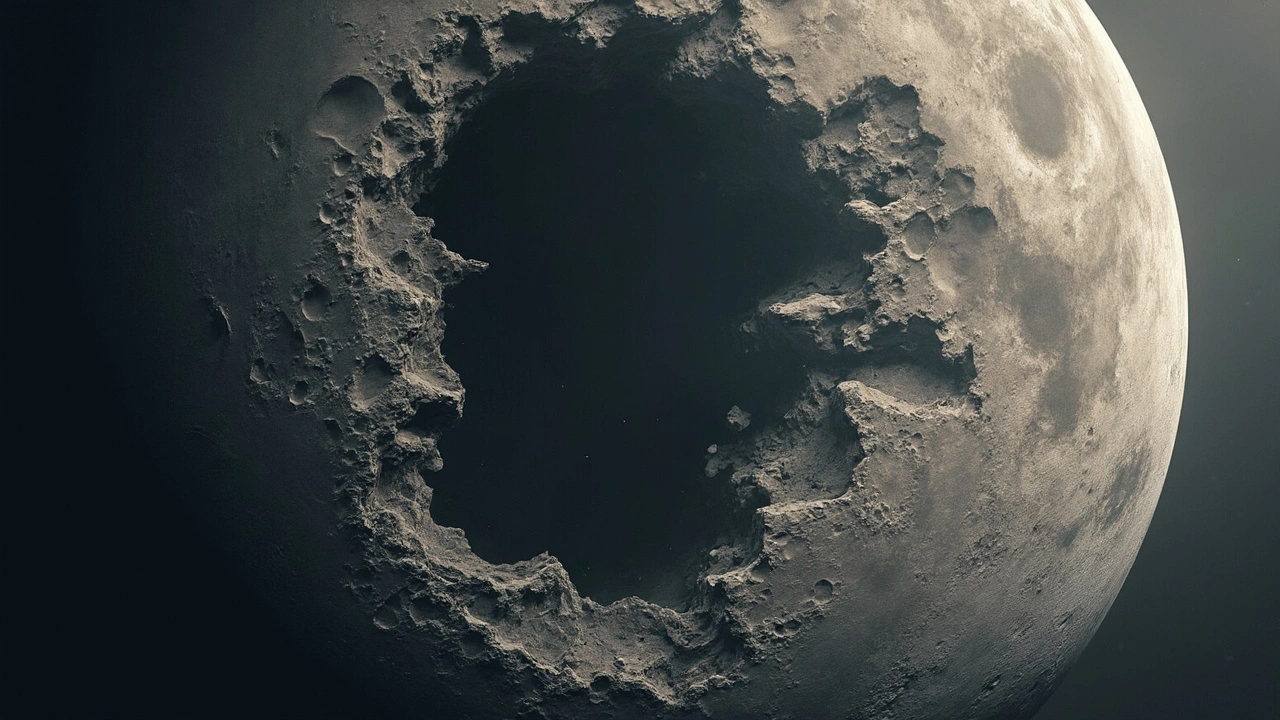

Before the space age, the moon’s far side was a blank canvas for storytellers, conspiracy fans, and science fiction writers. Poets guessed what lay hidden. Ancient cultures wondered if there were secret gardens or monsters just out of sight. The mystery got even juicier as telescopes improved and astronomers realized, with mounting frustration, that no trick or device could let them peer over the moon’s edge. The gossip about the dark side continued for centuries. That all changed in October 1959 when the Soviet spacecraft Luna 3 zipped behind the moon and snapped the very first fuzzy photos of the far side of the moon. The images—rough as they were—stunned the world. They revealed a jagged, heavily-cratered surface, worlds apart from the smoother plains (“maria”) of the near side. Suddenly, old legends hit the trash pile, and hard science took the spotlight.

After Luna 3 cracked open the lunar mystery, the United States joined the game with more missions in the 1960s and early ‘70s, including the famous Apollo landings. But even those astronauts, who set foot on the near side, never got a direct look at the far side unless they passed over it while orbiting. It wasn’t until cameras onboard Apollo spacecraft and later, satellites like NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, that we mapped the far side in stunning detail. The surface remains wild and rugged, with more craters and thicker crust than the side familiar to Earthlings. You’ll find the largest known impact basin in the solar system—South Pole–Aitken basin—carved into this far side, stretching about 2,500 kilometers wide and nearly 13 kilometers deep. If you want dramatic moon geography, this is it.

Newer tech brings fresh insights every year. In 2019, China’s Chang’e 4 probe landed on the far side, the first ever to do so. It didn’t just beam pretty panoramas back home—it carried seeds, small experiments, and a rover named Yutu-2 that scooted around, finding rocks, scanning underground, and searching for clues about the moon’s story. So, thanks to decades of science, we’re not in the dark on the science of the “dark side” anymore. If you’re hungry for data, here’s a quick rundown:

| Feature | Near Side | Far Side |

|---|---|---|

| Amount Seen from Earth | 100% | 0% |

| Major surface | Smoother, more maria | Rougher, more craters |

| Biggest crater | Imbrium Basin | South Pole–Aitken Basin |

The takeaway? Our ancestors’ fantasies were poetic, but reality is way cooler—alien, rugged, but totally sunlit and mapped with modern tech. The lunar far side is no longer science fiction; it’s all pixels and geology now.

Why the Far Side Is So Different

If you compare pictures of the moon’s two faces, it’s almost like looking at two planets. The near side (what you see from your backyard) has broad, dark plains—lunar maria—made from ancient lava flows. But swing around to the far side, and it’s mostly craters on top of craters, with barely any smooth maria in sight. Why this difference? Turns out, the moon’s insides are lopsided. Some scientists think early Earth’s gravity pulled on the moon more than we once expected, thinning the crust on the near side and letting lava leak out billions of years ago. The far side’s crust is thicker, so magma mostly stayed trapped below, leaving it rough and rocky. Basically, the near side had a construction job go smoothly, while the far side was like a half-finished, bumpy backyard project.

If you want to do a science party trick, memorize this: the near side’s maria make up about 31% of its face, but the far side’s maria cover only 1%. That huge South Pole–Aitken basin I mentioned earlier? It’s evidence of a giant impact, maybe one that shaped the moon’s structure long before humans were around. The far side also boasts more highlands—uplifts that probably formed as the basin’s crust rebounded after collision. It almost looks blasted, sculpted by billions of years of impacts that left the far side a bit battered and ancient compared to the near side’s smoother features.

You might wonder, how do scientists even study the far side in such detail without setting up camp there? Lots of it comes from remote sensing—spacecraft flying overhead, bouncing radar and lasers off the surface. Instruments measure minerals, scan temperature maps, and spot differences in soil chemistry. When China’s Chang’e 4 delivered the Yutu-2 rover, it even found traces of minerals that could hint at the moon’s hidden mantle, exposed by a giant smack long ago. Each mission uncovers something new; the story's not done yet.

The far side isn’t just different for science reasons—it’s the ultimate spot for future space adventures. With Earth out of sight, it’s radio-silent, perfect for building telescopes that catch whispers from across the universe. Imagine a giant lunar radio dish unfurling in one of those ancient craters, shielded from our noisy planet. Astronomers are dying to try it. The far side may be hidden from our daily view, but it’s got a prime seat for cosmic discoveries.

How You Can See More of the Moon—and Why It Captivates Us

So, can the average sky watcher see the far side of the moon with the naked eye? Not a chance. Your only shot is via photos or videos snapped by probes and astronauts. But here’s a fun loophole: the moon “wobbles” a little as it travels, an effect called libration. This cosmic wiggle lets us peek at about 59% of its surface over time, instead of just 50%. Think of it as the moon subtly showing us a shy shoulder now and then. If you track the moon’s edge with a telescope over several weeks, you’ll see just a sliver more than the usual view. That’s as close as you get from the ground.

If you’d love to experience the far side’s mysteries, dig into high-res images on NASA’s website or check out the LROC Observatory’s interactive moon map (a hyper-detailed online globe of our cratered neighbor). You can virtually spin the moon any way you want and zoom in on wild features like Tsiolkovskiy crater or the weird “Space Invaders” spot near Mare Moscoviense. Want to geek out even more? Check out lunar eclipse photos—those dramatic shots where the moon glows red as it passes into Earth’s shadow. It’s not the same as the far side, but it’s a cosmic event that shows off the moon’s place in our universe.

For dreamers and science fans, the far side holds endless appeal. If you catch a documentary about Apollo missions, listen for astronauts describing the eerie quiet of “radio blackout” when their spacecraft passed behind the moon, cut off from all communication. Or track the weird history of moon hoaxes and how the far side inspired endless cosmic stories—people have speculated about hidden bases, alien cities, or even lost civilizations. The reality is less dramatic, but just as fun in its own right: a battered highland world, bombarded by time, full of clues to the history of the solar system.

The moon is never really dark—just mysterious. Every time I look up, I remember what astronomers and astronauts have done to bring those hidden places into the light. Next time there’s a full moon, remember you’re staring at just one side. The far side is out there, just as real, wild and captivating, waiting for the next probe—or maybe, someday, a lunar tourist to snap a selfie and wave it back at the rest of us.

10 Responses

This is a fantastic dive into a topic that often gets misunderstood due to some common myths! For anyone curious, the so-called "dark side" of the moon isn't actually dark all the time — it's simply the far side that never faces Earth because of tidal locking. This means that while we see only one face from here, the other side experiences light and dark just like the side we do see.

Space missions, especially by probe satellites, have allowed us to map that mysterious far side, revealing a landscape quite different from the near side, with more craters and fewer maria. It highlights how important these missions are in broadening our understanding, not just relying on what we can observe with naked eyes from Earth.

It really sparks the imagination to think how much more there is yet to uncover about our closest neighbor in space!

Oh great, another article to tell us that the moon is just teasing us with one face! Honestly, it's kind of comical how something so visible can still hold such mysteries. But hey, I do appreciate this breakdown because it stops people from calling it the "dark side" incorrectly.

What really gets me laughing is how many conspiracy theories people have whipped up around the far side — like secret alien bases or hidden treasures. Spoiler alert: the far side is just a quiet, cratered rock, nothing more exciting than your average lunar surface.

Still, it's pretty cool how we’ve managed to peek behind that curtain thanks to space missions. Keep the space facts coming!

This was an interesting read! The tidal locking phenomenon that keeps the same face of the moon visible from Earth is a neat example of celestial mechanics in action. I appreciated how the article explained that the far side does get sunlight, it’s just out of our line of sight.

On another note, the detailed surveys of the moon’s far side have implications for future space exploration and maybe lunar bases. The unique terrain might offer different conditions, resources, or challenges compared to the near side.

Anyone here interested in what kind of scientific experiments we could set up on that side? I think it’s a promising frontier for human advancement in space.

Great post — or so it thinks it is!

Only half-kidding aside, I love how the ‘dark side’ term gets busted so often but never quite seems to go away. It’s one of those space facts recurring in pop culture like a bad penny. The moon’s far side is fascinating not because it’s dark or eerie but because it’s a glimpse into another geological story compared to the near side.

Has anyone ever wondered if the differences in maria and crater density might tell us something about the moon’s origins or how it evolved? Science nerds, assemble!

Yep, the moon is a classic example of tidal locking in action, and articles like this help clarify the misconceptions. But let's talk about how amazing it is that the far side is crater-heavy — that’s like Mother Nature’s lunar tattoo telling the story of what space bombardment looked like in the distant past.

Imagine living in a world where you only showed one side to your neighbors — kinda poetic, right? The fact that we now have satellite imagery peeling away the mystery is a testament to human curiosity and technological advancement.

Really looking forward to see what future missions will uncover, maybe even some surprises along the way.

So many people still get this wrong: the “dark side” doesn’t really exist as a perpetually dark hemisphere. It boggles the mind just how this term keeps spreading, despite clear scientific explanations. This article does well to confront that ignorance.

But beyond the semantics, the far side has distinct features, likely from its history and lack of volcanic maria that the near side has. This should affect how researchers approach lunar science and exploration.

We need more rigorous public education to squash these myths. Incorrect information hinders real appreciation of the incredible nature of our moon.

Ah! The moon! The mysterious orb in the night sky — so often romanticized yet so misunderstood! The dynamic between the near and far side is a fascinating topic that brings up philosophical questions about perception, reality, and what we assume based on limited views.

Isn’t it intriguing that we are forever bound to always see only one side of something so close to us? That unseen far side might even serve as a metaphor for the hidden aspects of knowledge or even ourselves.

This article serves as a gateway to not only lunar science but also to introspection about what we know and what remains beyond our immediate reach.

Honestly, the fixation on the 'dark side' shows how little people grasp basic astronomy. It's not about darkness but about perspective and orbital dynamics — and should be common knowledge by now.

That our distant neighbors can’t see the same side reveals a lot about the moon's synchronous rotation. It's prescient and highlights the limits of direct perception.

We could use more articles like this to cut through pop culture nonsense and ground everyone in actual facts. Otherwise, we’re stuck in the age of misinformation.

Honestly I think the whole fascination with the dark side is a bit overblown. It’s just the far side, there’s nothing inherently mysterious about it other than it’s out of sight from Earth. Lunar orbiters gave us all the info we needed ages ago.

People should focus more on upcoming lunar missions aiming to set up bases or experiments rather than romanticizing the shadows of that silent rock.

Still, gotta admit space stuff is cool even if all the hype sometimes feels like chasing shadows.

Oh, the moon finally gets its day in the sun (or dark) with this post? Seriously, the over-dramatization of the 'dark side' is just nonsense perpetuated by lazy media and sci-fi writers who skipped basic science class.

For those still confused, no, it’s not some mysterious different world but a side of the moon with rougher terrain and more craters. Get over it.

The hype around the far side fuels conspiracy theories and silly alien fantasies that only make the scientific truth harder to appreciate.

We need more straightforward, no-nonsense information like this article provides.