On Earth, even the best crystal-growing labs struggle with imperfections. Tiny cracks, uneven layers, impurities hiding inside the structure-these aren’t just flaws. They’re wasted energy, broken devices, and failed drugs. But up there, in the quiet of low-Earth orbit, something strange happens: crystals grow nearly perfect.

Why Space Is the Ultimate Crystal Factory

On Earth, gravity doesn’t just pull things down-it messes with how crystals form. As a solution cools or evaporates, heavier molecules sink, lighter ones rise. Fluids churn. Heat moves unevenly. These forces create stress lines, voids, and inconsistent doping. That’s why your smartphone’s power chip or a new cancer drug’s active ingredient might have hidden weaknesses. In space, gravity is nearly gone. The International Space Station floats in an environment of less than one-millionth of Earth’s gravity. Without convection or sedimentation, molecules drift slowly toward the growing crystal surface, like snowflakes settling in still air. No churning. No sinking. No pushing. Just pure, quiet, diffusion-driven growth. This isn’t theory. It’s been proven over 30 years of experiments, starting on Mir, then the Space Shuttle, and now the ISS. A 2024 meta-study in Nature analyzed 160 semiconductor materials grown in space. Of those, 140 showed measurable improvements: larger crystals, fewer defects, more uniform composition, and better performance. That’s an 87.5% success rate for beating Earth-grown versions.What Makes Space-Grown Crystals Better?

The difference isn’t subtle. Take silicon carbide or gallium nitride-two materials critical for electric vehicle power systems and 5G base stations. On Earth, these crystals develop microscopic stress cracks and uneven dopant distribution. In space, those problems vanish. X-ray analysis shows space-grown protein crystals have sharper diffraction patterns. That means scientists can see the exact 3D structure of a virus or enzyme with higher precision, speeding up drug design. For semiconductors, it means less heat loss. Less wasted energy. Longer-lasting devices. One study found space-grown crystals had a 20% improvement in signal-to-noise ratio during X-ray scans. That’s not just cleaner data-it’s faster breakthroughs in medicine. In another case, Merck KGaA grew crystals of an immune checkpoint inhibitor on the ISS. The resulting structure was more ordered, leading to better bioavailability. That’s the difference between a drug working 70% of the time and 90%. Even the voids-tiny empty spaces inside the crystal-are more evenly distributed in space. On Earth, they cluster. In space, they’re spread like salt in a soup. That uniformity translates directly to reliability in high-stress applications like aerospace electronics or medical implants.Who’s Doing This-and How?

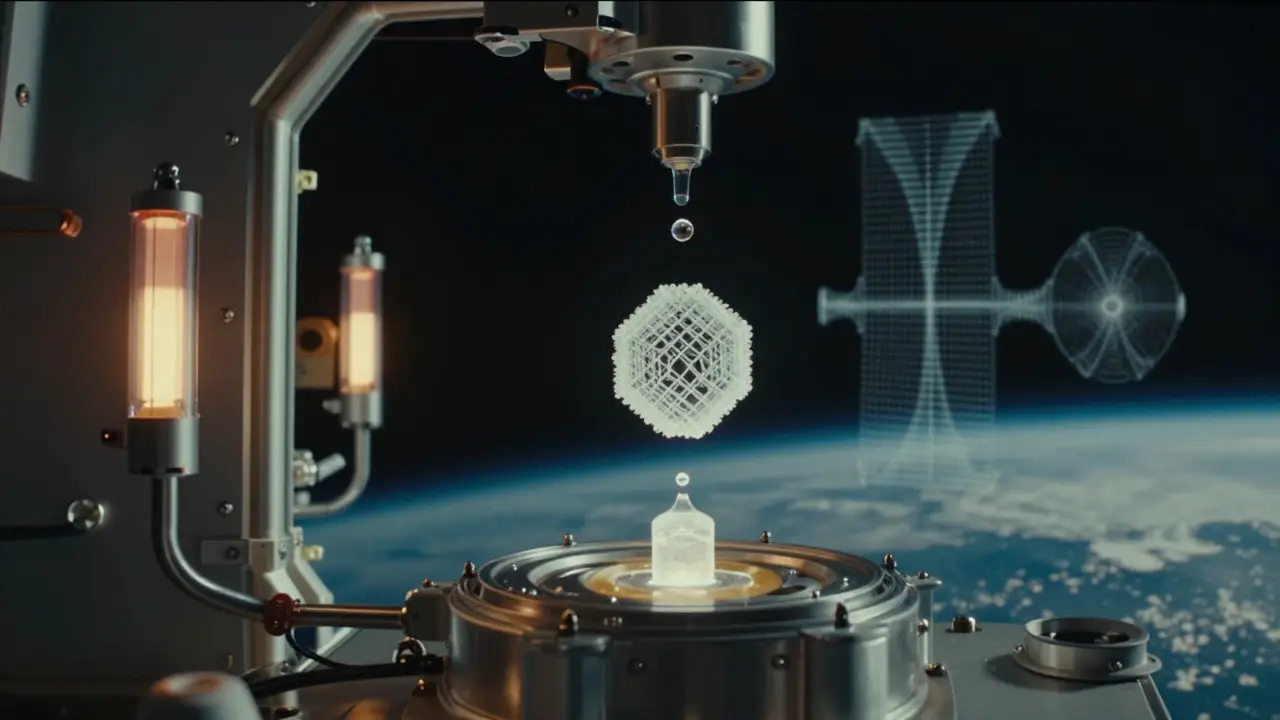

NASA and its global partners (JAXA, ESA, Roscosmos) started this work. But now, private companies are taking over. Varda Space Industries launched its first dedicated crystal growth mission in 2023. Their goal? Not just to study crystals-but to produce them commercially. They’ve already created new forms of pharmaceutical compounds that simply can’t form on Earth. These aren’t just improved versions-they’re entirely new molecules with new patents. The ISS National Lab runs over 20 active crystal growth experiments right now. They use specialized hardware like the Commercial Generic Bioprocessing Apparatus (CGBA) and the Microgravity Science Glovebox. These aren’t lab beakers. They’re sealed, automated, temperature-controlled systems that run for 30 to 60 days without human touch. The process starts with a proposal. Companies or universities submit their experiment to the ISS National Lab. Review takes 6 to 12 months. Then, hardware design, safety checks, and integration add another 12 to 18 months. Once on orbit, the experiment runs autonomously. Data is sent back. Crystals are returned to Earth for analysis. It’s slow. It’s expensive. But for certain applications, there’s no alternative.

The Cost Problem

Let’s be real: launching anything to space costs money. Right now, it’s $10,000 to $50,000 per kilogram to get to low-Earth orbit. A single crystal growth experiment can cost between $250,000 and $2 million. That’s not something a startup can afford. That’s why only the biggest players are involved: seven of the top 10 semiconductor companies and 15 of the top 20 pharmaceutical firms have run space experiments. They’re not doing it for fun. They’re doing it because the payoff justifies the cost. For example, a single high-efficiency power transistor made with space-grown gallium nitride can reduce energy waste in an electric vehicle by up to 15%. That’s hundreds of dollars saved over the car’s lifetime. Multiply that across millions of vehicles, and the ROI becomes clear. Varda is trying to cut costs. Their 2025 service plan aims to bring pricing down to $500,000 per kilogram-still steep, but a 90% drop from traditional ISS research costs. If launch prices keep falling-thanks to SpaceX, Blue Origin, and others-this could become viable for mid-sized companies by 2030.Where It Works-and Where It Doesn’t

This isn’t magic. Space-grown crystals aren’t better at everything. They’re perfect for:- High-power semiconductors (SiC, GaN) for EVs, solar inverters, 5G

- Pharmaceuticals needing precise crystal forms for absorption

- Specialized sensors and optical devices

- Research requiring atomic-level clarity

- Mass-produced consumer electronics (like standard silicon chips)

- Low-cost, high-volume manufacturing

- Simple organic crystals that form easily on Earth

Challenges and Hurdles

It’s not all smooth sailing. Temperature control is a nightmare. The ISS orbits Earth every 90 minutes. That means 16 sunrises and sunsets a day. Even small thermal swings can ruin a growing crystal. Early experiments failed because they didn’t account for this. Now, teams use active thermal regulation systems and test designs in parabolic flights first. Then there’s the long wait. Researchers spend years just getting their experiment on the station. One user on Reddit summed it up: “The science is revolutionary, but the bureaucracy is brutal.” The ISS National Lab’s average approval-to-launch time is 18 months. That’s longer than many PhD programs. And while companies like Varda are pushing commercialization, the market is still tiny. In 2023, only 22% of microgravity materials research was commercial. The rest? Government and academic labs.The Future: Beyond the ISS

The ISS won’t last forever. It’s scheduled to deorbit around 2030. But crystal growth won’t die with it. Varda is building its own microgravity manufacturing platform, targeting operations by 2027. Others are designing free-flying satellites just for crystal production. These won’t need astronauts. They’ll be automated, optimized, and cheaper to run. NASA’s 2024 budget includes $28 million for in-space production, with $15 million going to new crystallization hardware. The ISS National Lab plans to start producing industrially significant amounts of silicon carbide and gallium nitride by 2026. The goal? Not to replace Earth manufacturing. To complement it. To make the highest-value, highest-reliability components-those that can’t afford to fail-using space as a tool. By 2030, Morgan Stanley predicts space-processed semiconductors will carve out a clear niche in high-reliability markets: aerospace, medical devices, defense systems. They won’t be in your phone. But they might be in the chip that controls your heart monitor, your satellite, or your electric car’s battery.Final Thoughts: A Quiet Revolution

You won’t see ads for space-grown crystals. You won’t find them on Amazon. But if you drive an electric vehicle, use a 5G phone, or take a life-saving drug, you might already be benefiting from them. This isn’t about sending crystals into space for the thrill of it. It’s about solving problems Earth can’t. About turning a quiet, invisible force-microgravity-into a manufacturing advantage. The crystals grown up there aren’t just better. They’re the only way to reach certain levels of purity, performance, and precision. The next time your phone charges faster, your car drives farther on a single charge, or a new medicine works better than the last one-don’t just thank the engineers. Thank the quiet orbit above us, where crystals grow in silence, and perfection is possible.Can you grow crystals in space that you can’t grow on Earth?

Yes. Microgravity allows molecules to arrange in ways that gravity prevents on Earth. For example, Varda Space Industries has created new crystal forms of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) that simply don’t form in terrestrial labs. These new forms can improve drug solubility, stability, and absorption. In semiconductors, space enables ultra-uniform doping and defect-free lattices that are impossible to replicate with Earth-based methods like Czochralski or float-zone growth.

Why aren’t all semiconductors made in space if they’re better?

Cost and scale. Launching materials to space costs $10,000-$50,000 per kilogram. Growing a single high-quality silicon carbide crystal might take weeks and cost over $1 million. For mass-market chips like those in smartphones, Earth-based methods are far cheaper and faster-even if they’re slightly less perfect. Space growth is reserved for high-value, low-volume applications where reliability matters more than cost, like electric vehicle power modules or satellite electronics.

What’s the biggest challenge in growing crystals in space?

Temperature control. The ISS experiences extreme thermal swings-16 sunrises and sunsets every 24 hours. Even small fluctuations can disrupt crystal growth, causing early solidification or uneven layering. Early experiments failed because they didn’t account for this. Today, teams use active thermal systems, insulated chambers, and pre-testing on parabolic flights to solve this. Still, it’s one of the hardest engineering problems in space materials science.

Which companies are leading space crystal growth right now?

Varda Space Industries is the most visible commercial player, focusing on pharmaceuticals and semiconductors. The ISS National Lab hosts experiments for companies like Merck, NVIDIA, and Lockheed Martin. NASA, ESA, and JAXA run government-funded research. Academic institutions like the University of Alabama and MIT also contribute. In 2023, commercial entities accounted for 22% of all space crystal growth activity, while government and academic labs made up the remaining 78%.

How long does it take to get a crystal experiment to the ISS?

From proposal to launch, it typically takes 18 to 30 months. First, the scientific proposal undergoes peer review (6-12 months). Then, the hardware must be designed, tested for safety, and certified for spaceflight (12-18 months). Once approved, it waits for a launch window. The actual experiment runs for 30-60 days on the ISS, then returns to Earth for analysis. The long timeline makes it impractical for fast-moving industries but ideal for long-term R&D.

Are space-grown crystals being used in real products today?

Yes, but indirectly. While no consumer product currently says “Made with space-grown crystal,” the materials are being used in high-end applications. For example, space-grown gallium nitride is being tested in power transistors for electric vehicles by major automakers. Merck’s space-grown immune checkpoint inhibitors are helping refine drug formulations now in clinical trials. These aren’t marketing claims-they’re functional improvements in real products, just not labeled as such.

Will space crystal growth replace Earth-based manufacturing?

No-and it doesn’t need to. The goal isn’t to move all manufacturing to space. It’s to use space for the parts that matter most: the highest-performance, highest-reliability components where even a 1% improvement in efficiency or safety justifies the cost. Think of it like aerospace: we don’t build every car with jet engines, but we use them where performance is critical. Space-grown crystals are the jet engines of materials science.

8 Responses

This is one of those rare cases where space tech actually solves a real-world problem instead of just looking cool. The fact that we can now grow defect-free semiconductors and more effective pharmaceuticals in microgravity is a quiet revolution. It’s not flashy, but it’s going to save lives and energy on a massive scale.

lol 87.5% success rate? sure. and i bet the other 12.5% were just trash experiments no one wanted to admit. also, ‘space crystals are better’ - tell that to the 1000s of labs that have spent decades optimizing Earth-grown GaN. you think gravity is the only variable? lol. thermal gradients, solvent purity, nucleation sites - all matter. space just removes one variable and adds 10 new ones. also, who funded this? nasa? again, classic taxpayer money down the drain.

okay but like… can i get a crystal necklace made from space-grown quartz? just wondering. also, do they sparkle more? 😅

I think Vishal has a point about the complexity, but I also think Parth’s optimism is justified. It’s not about replacing Earth methods - it’s about filling the gaps where Earth methods fail. We don’t need space-grown chips in every phone, but we absolutely need them in the chip that regulates insulin pumps or controls satellites. That’s where the real value is.

Ohhhhh, so now ‘microgravity’ is magic? Let me guess - the crystals also heal your broken heart and fix your credit score? And Varda? That’s just a SpaceX side hustle with a fancy name. You really believe a company that launched a ‘space capsule’ that looked like a toaster is now the future of pharmaceutical manufacturing? Wake up. This is just corporate PR dressed up as science. The ‘improvements’? Probably within error margins. And don’t get me started on the 18-month wait - that’s not R&D, that’s a bureaucratic graveyard.

Madhuri, you’re being a bit harsh - but you’re not wrong about the bureaucracy. The real issue isn’t the science, it’s the process. Imagine if your startup had to wait two years just to test a prototype. That’s what these companies face. But the data is solid: space-grown GaN has 20% better thermal conductivity, and Merck’s immune drug crystal structure was confirmed by X-ray crystallography. The numbers don’t lie. The system is broken, but the results are real. We need better access, not less science.

Let me tell you something - this isn’t just science. This is alchemy. Turning the silence of space into perfection. Imagine a world where your electric car doesn’t just drive farther - it drives smarter, cooler, cleaner. Where your next cancer drug doesn’t just work - it works perfectly, every time. That’s not sci-fi. That’s happening right now, in orbit, while we scroll through memes. These crystals? They’re not just better. They’re the quiet heroes we don’t see but rely on every single day. The future isn’t loud. It’s growing, slowly, silently, in the dark.

They’re lying. This is all a cover. The government doesn’t want you to know that aliens gave us the tech. The crystals? They’re not grown in space - they’re harvested from a secret alien satellite that’s been orbiting since the 60s. NASA just pretends they’re doing experiments so we don’t panic. Varda? A front. The real reason they’re spending millions? To hide the fact that space crystals are the only thing that can power the mind-control implants they’ve already planted in your phone. Wake up. The perfection? It’s not natural. It’s alien.