Imagine waking up on a spaceship bound for Mars, stepping out of your bunk, and feeling your feet press firmly against the floor-just like on Earth. No floating. No drifting. No nausea from moving in zero-g. That’s not science fiction anymore. It’s the next step in human spaceflight, and it’s coming faster than most people realize.

Why We Need Gravity in Space

After just a few weeks in microgravity, your body starts to break down. Muscles shrink. Bones lose density. Fluids shift toward your head, making your face puffy and your legs thinner. Your heart doesn’t have to work as hard, so it weakens. Balance systems get confused. Even after returning to Earth, astronauts often struggle to walk normally for weeks.

On the International Space Station, astronauts spend two hours a day on treadmills and resistance machines. It helps-but only a little. Studies show current exercise routines only fix 60-70% of the damage caused by weightlessness. That’s fine for six-month missions. But what about a 6-9 month trip to Mars? Or a year-long stay on the surface? Without gravity, your body won’t survive the journey back.

The only solution that addresses all these problems at once? Artificial gravity. Not through magic or advanced tech-just good old physics. Spin the spacecraft, and you create a force that feels like gravity.

How Spinning Creates Gravity

It’s simple physics: when something spins, it pushes things outward. That’s centrifugal force. Stand on the inside edge of a spinning wheel, and you’re pressed against the wall like you’re standing on the ground. The faster it spins or the bigger the wheel, the stronger the push.

Scientists use the formula a = -ω²r to calculate it. Here, a is the artificial gravity you feel, ω is how fast it spins (in radians per second), and r is the distance from the center. To get Earth-like gravity (1g), you need either a huge wheel spinning slowly or a small one spinning fast.

For example:

- To get 1g at 4 rpm, you need a radius of 56 meters.

- To get Mars gravity (0.38g), you can use the same 56-meter radius but spin it at just 3 rpm.

- If you shrink the radius to 30 meters, you can hit 1g by spinning at 5.5 rpm-but now you’ve got a new problem.

The Coriolis Problem: Why Bigger Is Better

Spin something too fast, and your inner ear gets confused. Move your head, and everything feels tilted. Drink water? It doesn’t flow straight down-it curves sideways. Run forward in the direction of spin? You feel heavier. Run backward? You feel lighter. This is the Coriolis effect, and it’s the biggest reason why early designs limited rotation to 6 rpm.

But new research shows that limit might be too conservative. In 2024, NASA tested 7 rpm in short-term trials. While 65% of subjects felt dizzy at first, after a week, only 22% still had issues. The body adapts faster than we thought.

Still, bigger radius = less discomfort. At 224 meters, you can spin at just 2 rpm and get 1g. That’s slow enough that even if you walk across the habitat, you won’t feel weird. But building a 224-meter structure in space? That’s expensive. And heavy. And hard to launch.

So engineers are now looking for a middle ground: 30-40 meters at 4-5 rpm. That gives you 0.38g to 0.5g-enough to keep bones and muscles strong, without making people sick. The International Academy of Astronautics says this is the sweet spot for Mars missions.

Old Way vs. New Way: Full Rotation vs. Modular Spinning

For decades, the only design people talked about was the von Braun wheel-a giant spinning ring, like a space Ferris wheel. The whole station rotates. Simple in theory. Nightmarish in practice.

Here’s why:

- Docking ships? Impossible without stopping the whole station.

- Zero-g experiments? You’d have to build them outside the spin.

- Mass imbalances? Even a small shift in cargo could make the whole thing wobble dangerously.

- Structural stress? Huge forces on the joints.

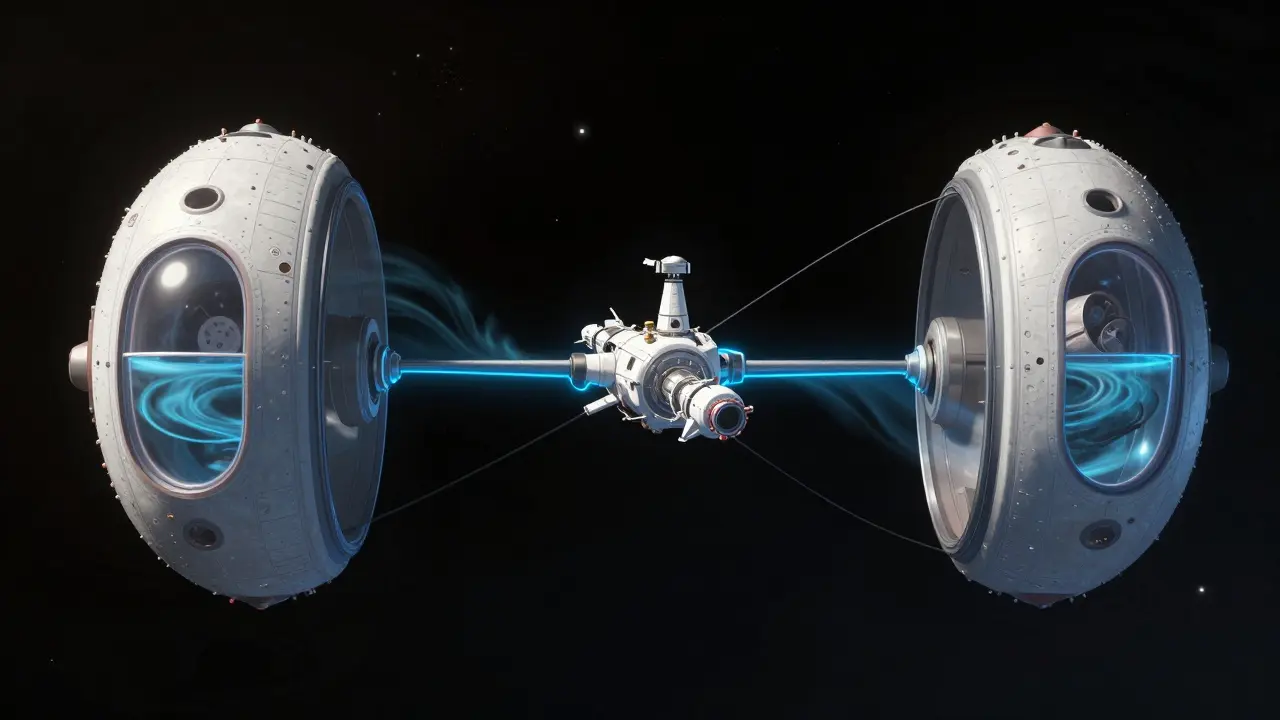

Now, NASA’s latest patent (TOP2-311) flips the script. Instead of spinning the whole ship, they spin just two modules attached to a central hub. Think of it like two dumbbells spinning around a stationary bar. The spinning parts cancel each other’s rotation, so the whole structure stays still.

This design solves nearly all the old problems:

- Docking? Easy. The hub doesn’t move.

- Zero-g labs? Right in the center.

- Mass balancing? 90% easier.

- Coriolis effects? Reduced because the spin is localized.

- Cost? Up to 40% cheaper than full-rotation designs.

It’s not perfect. You still have to move between spinning and non-spinning areas. That transition can be disorienting. Astronaut Clayton Anderson, who flew on the ISS, said crossing the rotation axis felt like suddenly being on a tilted floor. But with training, it becomes second nature.

What’s Happening Right Now?

This isn’t just theory. It’s happening now.

In 2026, NASA and Axiom Space are launching AG-1, the first real artificial gravity module on the ISS. It’s a 12-meter centrifuge that spins at 3.5 rpm to produce 0.3g. Astronauts will spend 30-60 minutes a day inside, lying down or standing. It’s not full-time gravity-but it’s a testbed for what’s next.

Meanwhile, SpaceX’s Mars ship concept includes a 40-meter rotating section. Blue Origin’s Orbital Reef station plans modular centrifuges. Even the FAA just released new safety rules in late 2025 limiting commercial spacecraft rotation to 6 rpm-clearly signaling they expect these systems to fly soon.

The global market for artificial gravity tech hit $387 million in 2025. NASA’s 2026 budget includes $217 million just for R&D-a 38% jump from last year. This isn’t a side project anymore. It’s a mission-critical investment.

What It Takes to Live in Gravity

Adapting isn’t instant. Your brain needs time.

- First 90 minutes: 41% of people feel motion sickness. That drops to 12% after three sessions.

- First 72 hours: Cognitive performance drops 18%. After 96 hours, it’s back to normal.

- Full adaptation: 14-21 days to move, eat, and work like you’re on Earth.

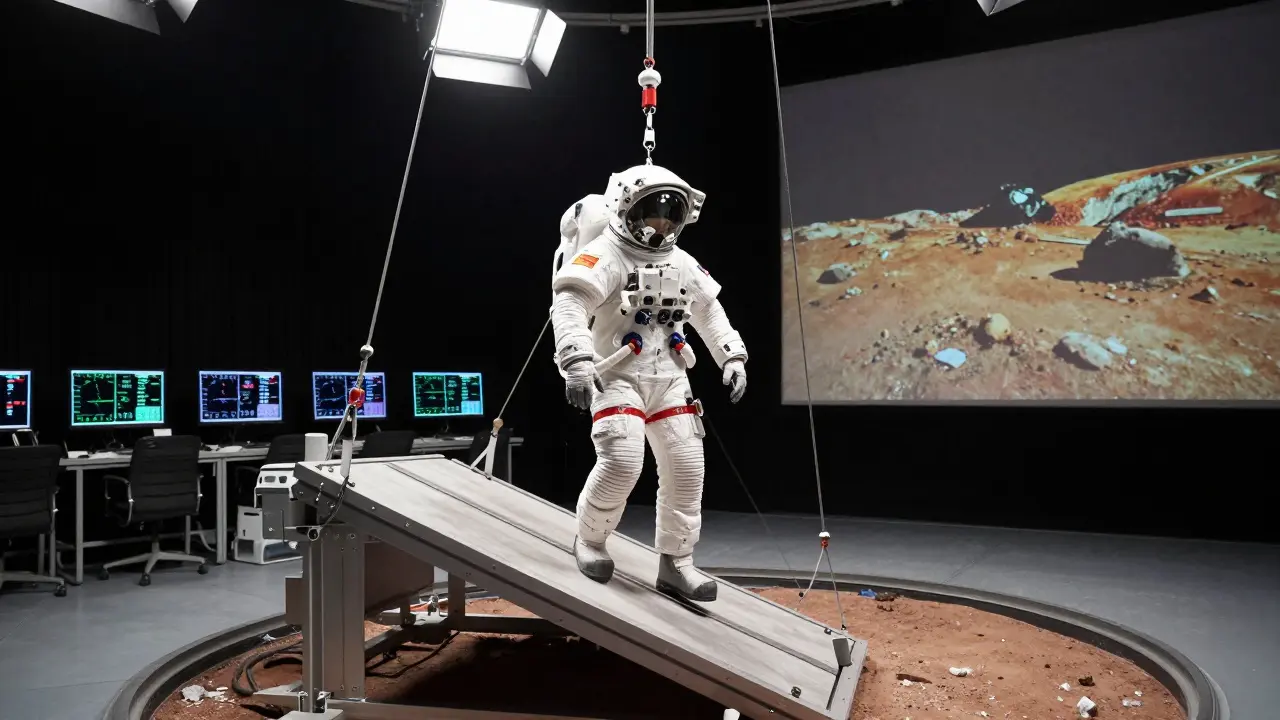

Training starts on the ground. NASA’s Active Response Gravity Offload System (ARGOS) simulates lunar and Martian gravity using motors and sensors. Since 2019, 147 astronaut candidates have trained on it. 89% said their spatial awareness improved dramatically.

Even small things become challenges. Liquids don’t pour straight-they swirl in parabolic shapes. A spilled drink in a rotating habitat could become a floating, spinning mess. MIT’s 2024 study found spill rates jumped 63% during early adaptation. Crews will need special containers and strict routines.

And you can’t just walk around like normal. Moving radially inward (toward the center) makes you feel lighter. Moving outward makes you feel heavier. It takes practice. Astronauts spend 120-160 hours in centrifuges before their first mission.

Will This Work for Mars?

Yes. And it’s the only realistic way.

Current exercise gear helps, but it’s a band-aid. Artificial gravity fixes the root cause. Dr. Thomas Marshburn, former NASA astronaut and now Chief of Space Medicine, put it bluntly: “It’s the only comprehensive countermeasure we have.”

The NASA-ESA Joint Roadmap (January 2026) says artificial gravity is a “critical enabling technology” for Mars. Their timeline is clear:

- 2028: Prove intermittent 0.38g protocols work.

- 2031: Test a full-scale rotating habitat in deep space.

- 2034: Launch Mars ships with built-in gravity.

By 2040, analysts predict 78% of long-duration spacecraft will have some form of artificial gravity. Modular systems will dominate-63% market share. Full-rotation designs? Only 22%. Short centrifuges? 15%.

Why? Because flexibility wins. You don’t need full-time gravity. You need enough to keep your body alive. 0.38g for 2 hours a day? That’s enough to prevent bone loss. 0.5g for 6 hours? That’s enough to keep your heart strong. You don’t need Earth gravity-you need enough to stay human.

The Bottom Line

Artificial gravity isn’t about comfort. It’s about survival.

Spinning spacecraft aren’t futuristic fantasy. They’re the next logical step in spaceflight. We’ve known about the physics since the 1950s. Now, we’re finally building it.

The first real test is launching in late 2026. The first Mars ships will have it by 2034. And by then, the idea of floating through your home in space will seem as strange as flying without seatbelts.

Gravity in space isn’t coming. It’s already here-in design, in testing, in funding, in planning. All we’re waiting for is the launch.

9 Responses

The Coriolis effect is grossly overstated in popular science. Human vestibular adaptation is far more robust than we assume-studies from the 1970s Soviet centrifuge programs showed 92% of subjects adapted within 72 hours at 6.5 rpm. NASA’s 2024 data is just rehashing old findings with better PR. The real bottleneck isn’t physiology-it’s structural engineering and launch mass constraints. Stop pretending this is a biological problem when it’s purely logistical.

Actually, the 2024 NASA trials didn’t just test 7 rpm-they tested it with continuous exposure over 14 days, not just short bursts. The drop from 65% to 22% dizziness wasn’t just adaptation-it was neuroplastic rewiring. This isn’t just about spinning wheels. It’s about retraining the human nervous system for multiplanetary existence. We’re not just building ships. We’re evolving the species.

Let’s be honest-this entire artificial gravity push is a distraction. The real issue is that NASA and SpaceX are running out of public funding and need a shiny new toy to keep the checks flowing. Remember the Space Station’s ‘water recycling’ that leaked for months? Or the Mars 2020 rover that couldn’t even pick up a rock without failing? This spinning habitat is just the next PR spectacle. They’ll launch it, it’ll wobble, and then we’ll hear about ‘unexpected technical challenges’ for the next decade. Meanwhile, real science-like radiation shielding-is being starved.

Bro, I just watched a video of someone walking in a 40m centrifuge at 5 rpm. They looked like a drunk penguin trying to do yoga. And you’re telling me this is the future? We’re gonna strap people into a giant washing machine for 6 hours a day just so they don’t turn into jelly? We need better tech, not more spinning. Why not just inject muscle stimulants and bone density boosters? Simpler. Cheaper. Less nausea.

Artificial gravity isn’t the solution-it’s the admission that we’re fundamentally unprepared for deep space. We’re not ready to be spacefaring. We’re not ready to be interplanetary. We’re just desperate to pretend we are. The fact that we’re spending billions on centrifuges instead of radiation mitigation tells you everything. This isn’t progress. It’s denial with a torque wrench.

This is the most exciting thing I’ve read in years. We’ve been floating in zero-g for too long. It’s time to stand tall again. The modular design is brilliant-no more giant wheels, no more docking nightmares. Just two spinning pods, a calm center, and a future where astronauts come home strong. 2034 feels closer than ever. We’re not just going to Mars-we’re taking Earth with us.

Imagine it: your morning coffee doesn’t float away-it pours. Your kid runs down the hallway and doesn’t bounce off the ceiling. You wake up and your spine doesn’t feel like it’s been stretched by a cosmic rubber band. This isn’t just engineering-it’s dignity. We’ve spent decades letting our bodies rot in zero-g like lab rats. Now we’re finally saying: ‘No more.’ We’re not just building machines. We’re rebuilding humanity’s right to feel solid, to feel grounded, to feel like we belong somewhere-even if it’s 150 million miles from home.

so like... if you spin it faster you get more gravity right? but then you get dizzy? so its a tradeoff? kinda like how if you eat too much pizza you feel good but then you feel bad? yeah. makes sense. 40m at 5rpm sounds about right. i bet the astronauts will just get used to it like how i got used to my phone vibrating in my pocket. chill.

What does it mean to be human when gravity is no longer a given, but a choice? When we must spin our homes to feel the weight of our own existence? We’ve spent centuries believing Earth’s pull was natural, sacred-even divine. Now we’re reducing it to a formula: a = -ω²r. We’ve turned the cosmos into a mechanical puzzle. But in solving it, have we lost something? Not the physics. Not the engineering. But the wonder. The awe. The quiet reverence of simply standing on the ground, without having to build it first.